Whether it’s bread or onions, food has the power to make or break a country’s leadership. How nations secure their staples is looming large in elections across the world with war in Ukraine and now the Middle East.

Starting with New Zealand and Poland this weekend, at least a quarter of the global population will head to the polls over the next eight months or so. Those countries will be followed by Argentina, the Netherlands and Egypt, and then Indonesia and India in 2024. Among them are some of the top suppliers of everything from rice and palm oil to milk and soymeal. Others are strategic locations for the flow of staples like wheat.

Politicians have an eye on two core constituents: consumers and producers. Some governments aiming to stay in power are restricting exports of foodstuffs, proposing measures to protect rural communities, or slowing the pace of climate policies that would affect farmers.

Food is just one of a long list of electoral issues, but it has global repercussions. The politics threaten to impact global trade, prices and the economies of import-dependent nations. Erratic weather, meanwhile, has ravaged agricultural land from the US to China, and the phenomenon known as El Niño is back, risking further damage to crops.

Then there’s war. Before Russia’s invasion, Ukraine exported more grain than the entire European Union combined and supplied half of the globally traded sunflower oil. The conflict between Hamas and Israel pushed up the price of crude oil, which could have a knock-on effect for food production. The expectation is that Israel is preparing a ground war after vowing to wipe out the Iran-backed militants.

“We are in a world where everybody’s pandering to domestic issues,” said Tim Benton, a research director at Chatham House in London specializing in food security. “That world of protectionism driven by elections and polarization and inward-looking domestic politics might well play out large.”

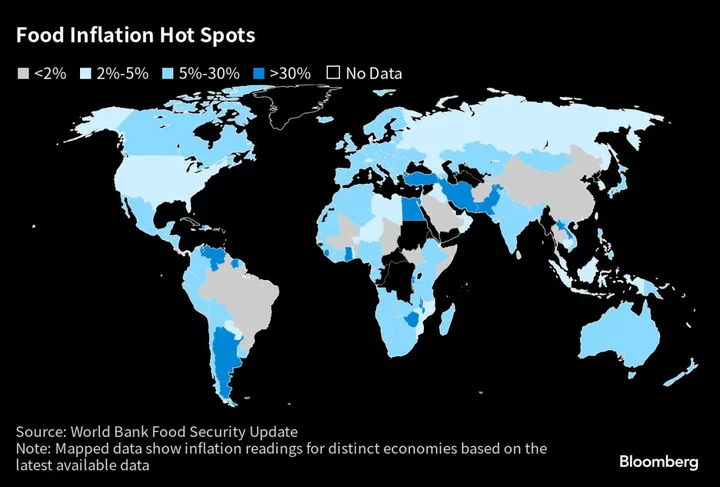

Politicians have reasons to be nervous. Food price spikes can trigger food riots around the world. In 2011, they contributed to the Arab Spring uprisings in Egypt and elsewhere in the Middle East, a region in turmoil again. Meanwhile, central bankers and governments everywhere are struggling to contain food costs that are outpacing core inflation.

Climate politics have emerged as a defining line between the left and right. In Europe and the Americas, the issue of conflating climate change, globalization and the protection of local production is aligned with the resurgence of more radical parties, according to risk intelligence company Verisk Maplecroft.

“When you’re talking about very polarized and tight elections, this thematic campaigning for specific groups can make the difference between a victory and a loss,” said Jimena Blanco, chief analyst at the firm.

These are some of the countries to watch.

Curbing Emissions

The world’s biggest milk exporter, New Zealand vowed to curb the devastating impact on the environment from agriculture, but farmers aren’t happy because taxing greenhouse gas from cows threatens their business.

Ahead of an Oct. 14 election, the government delayed the implementation of so-called emissions pricing until toward the end of 2025. The main opposition party wants to push it back until 2030.

In the Netherlands, the world’s second-largest exporter of agricultural produce, farmers have turned into a political force before elections in November. A goal to halve nitrogen emissions by 2030 led to protests, and the upstart Farmer-Citizen Movement, or BBB, is now the largest party in the Dutch upper house and fourth in opinion polls. The governing coalition retracted their emissions goal.

Grain Feud

Food costs and production have been key themes in the bitter political campaign in Poland ahead the Oct. 15 election. Last time, about two-thirds of farmers backed the nationalist Law and Justice party, which is trying to secure a third term in power. The war next door in Ukraine, surging costs and drought have made the group critical for the ruling party again.

To calm restive farmers, the government defied the EU and extended an embargo on Ukrainian grain. Ukraine President Volodymyr Zelenskiy filed a complaint with the World Trade Organization and questioned Poland’s solidarity. Polish leaders warned Zelenskiy that his rhetoric could jeopardize future weapons shipments.

Law and Justice, which has been battling to protect a narrow lead in the polls against its more pro-EU, liberal opponent, is also luring farmers with promises to make supermarkets offer more local food.

Opposition leader Donald Tusk, an ex Polish premier and former European Council president, has sought to mollify the radical leader of the farmers. In a media briefing last month, they spoke in front of a cabbage field, promising to deliver a compromise with the EU over the ban on Ukrainian grain imports.

Unshackling Farmers

The presidential election in Argentina takes place a week later. The nation is a top global supplier of beef as well as soybean meal and corn to feed livestock in other countries. But farmers haven’t been able to fully tap the potential of vast flatlands because of years of export taxes to boost revenue and efforts to curb inflation still running at more than 100%.

Libertarian candidate Javier Milei, the shock front-runner, plans to unleash an export boom and dismantle policies that have held back agricultural investment. Milei would scrap export taxes and quotas and remove direct meddling in food prices. That’s in addition to his controversial policy of switching Argentina’s currency from the peso to the US dollar.

Critical to farmers is whether they end up with more cash to invest in planting, and in turn provide the world with another source of food.

Critical Imports

One of the world’s biggest wheat importers, Egypt knows better than many other nations the power of food on politics. Surging wheat prices contributed to the discontent behind the Arab Spring that toppled governments in the region just over a decade ago.

Today, that dependence coupled with the shortage of dollars needed to buy more food are conspiring to keep inflation high as the nation reels from its worst economic crisis in years. There’s also now the question of war on its doorstep. That’s presenting a challenge for President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi, who is seeking another term in December elections.

The government in Cairo is looking for ways to lower prices of consumer goods, especially key commodities. It’s already temporarily banned exports of onions to control prices and is working with the central bank to ensure availability of dollars, with the aim of bringing down costs.

Hunger Threat

Food is a touchy subject in India, a country where ruling political parties lost elections because they couldn’t control the price of onions. Stable prices are crucial for Prime Minister Narendra Modi as he seeks a third term next year.

Retail inflation returned to within the central bank’s target level in September thanks to an easing of food costs, but the prices of staples like grains, pulses and spices are still high compared with a year earlier.

The government is considering increasing cash support to small farmers, its core constituency. It’s restricted shipments of wheat, might scrap a tariff on imports and is expected to curb sugar exports after dry weather parched crops. Most importantly, though, the world’s top rice exporter has restricted shipments of the staple consumed by half the world, boosting prices and increasing the risk of political instability in Asia and Africa.

Food Vs Fuel

President Joko Widodo’s Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle singled out food security as a priority as Indonesia tries to cut reliance on food imports. Policymaking has been mired recently by a corruption scandal, costing the agriculture minister his job. The country is due to hold elections in February before Widodo steps down in October after serving his second and final term.

The world of trade and climate is watching palm oil, found in everything from peanut butter to shampoo. Indonesia produces more of it than anyone else and it’s been directing more of the commodity into biofuels, an attempt to cut its burgeoning diesel import bill. The targets have been ambitious and any abrupt changes, big or small, can send reverberations across the food market.

Farming the commodity is also a key cause of deforestation. While Indonesia has been attempting to crack down for some time, enforcement has been patchy and research has shown electoral considerations often deter the authorities from taking on farmers. In a rush to secure votes, there are risks that politicians will turn a blind eye to land clearing.

--With assistance from Agnieszka Barteczko, Cagan Koc, Anuradha Raghu, Pratik Parija, Tracy Withers, Michael Ovaska, Jody Megson, Michael Gunn, Mirette Magdy, Jonathan Gilbert, Patrick Gillespie and Megan Durisin.