When March’s bank failures ignited a historic bond rally, few, if any, made more money than Josh Barrickman.

His army of funds gained roughly $26 billion, the equivalent of more than $1 billion in paper profits every single trading session.

Yet Barrickman didn’t predict Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse, or Credit Suisse’s tortured final days. He doesn’t even have a view (at least that he’s willing to share) on what the Federal Reserve will do next.

He runs Vanguard Group Inc.’s $1 trillion bond indexing business for the Americas, a class of investing that — to the outside world, at least — is as vanilla as it gets.

There’s nothing vanilla about the money he’s pulling in, though. The soft-spoken 47-year-old’s funds lured $31 billion last year, even as active managers posted unprecedented outflows amid the worst year for bonds since at least 1977. In fact, he now controls nearly as much US debt — including Treasuries, agency and corporate bonds — as China, America’s second-largest foreign creditor.

That makes Barrickman exhibit A of a passive management revolution that’s reshaping the world of fixed-income, just as it did equities a decade ago. No longer dominated by traders making multimillion-dollar bets and eating what they kill, the real money is flowing to guys like him, whose decisions are increasingly rippling through markets.

“We do have size and scale, and that matters in the marketplace,” Barrickman said in an interview. “Tracking is job one, two and three,” he said, adding “if we can have a basis point a year, that’s a lot of real money.”

Equity investors have been shifting to passive index products for years. Created decades ago, their popularity ballooned following the 2008 financial crisis, fueled in part by skepticism of active money managers after stocks cratered.

The transition has been slower in fixed-income. Indexes are made of tens of thousands of over-the-counter bonds, many of which are so illiquid they won’t change hands for weeks at a time. It’s hard to buy the entire market the way equity investors can buy every stock, making it more difficult for an index fund to track the performance of its benchmark closely.

Indeed, the fixed-income market has long been seen as more complex relative to stocks, allowing firms to justify the need for active management, and the juicier fees that come with it.

But history is repeating. The dramatic losses in debt markets last year, fueled by the most aggressive Federal Reserve policy tightening in a generation, has turned what was once a relatively slow and steady shift away from active bond funds and toward passive products into a stampede.

The gap between passive and active net flows reached a record $1.04 trillion in 2022, almost triple any other year, according to data from EPFR. Passive funds lured $279 billion in new cash, while active funds bled $757 billion.

As of March, assets managed by passive funds surpassed $3 trillion for the first time. They now account for 31% of the fixed-income fund universe, the data show, up from just 13% a decade ago.

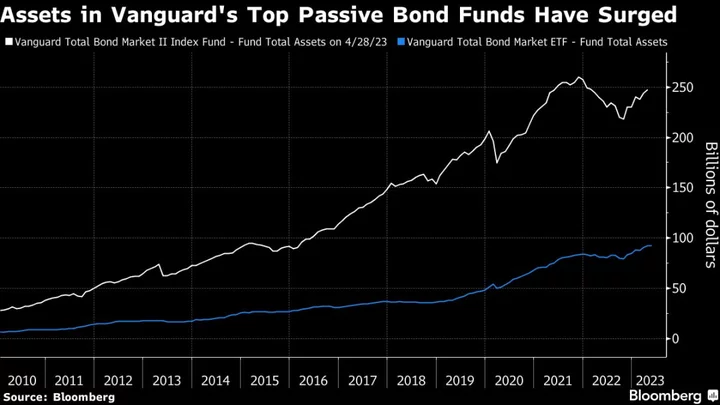

Barrickman himself now oversees three of the world’s four largest bond funds, including the $298 billion Vanguard Total Bond Market Index Fund, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

That means many of the decisions he makes, like which bonds to buy when trying replicate his funds’ underlying benchmarks, can have big consequences for the market (the Vanguard Total International Bond Index Fund, for example, only holds roughly half the 13,000 bonds in the index it tracks.)

“We have to be, by definition, overweight some places and underweight others to build a sample,” Barrickman said. “We’re dealing in a market that forces us to take some active positions.”

Moving Market

Beyond Vanguard, the other big beneficiary of the shift from active to passive in fixed income has been BlackRock Inc. The firm’s more than 90 US index-tracking bond ETFs have taken in over $100 billion in the past year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, more than any other firm.

Gang Hu, managing partner at Winshore Capital Partners, which specializes in inflation-protected investments, said passive funds, particularly those run by Vanguard and BlackRock, have become so big and influential that he keeps a spreadsheet tracking their daily flows. Their impact is particularly significant toward the end of the month, when funds move large swaths of securities around to accommodate investment flows, new issuance and maturing bonds as their benchmarks rebalance.

“Everyone watches their flows,” Hu said. “They could easily move the market. You have to anticipate their moves.”

The sheer size of passive mutual funds and bond ETFs run by Barrickman and a few others have changed the dynamics of the market in recent years, said Thomas di Galoma, co-head of global rates trading at BTIG.

“There used to be a time in the bond market when a lot of funds would move on the last day of the month,” he said. “But because they are so large now, they have to move days before month-end,” which means their position adjustments affect yields for a longer period.

A native of Ohio, Barrickman graduated from Ohio Northern University before earning his MBA from Lehigh University. In 1999, he joined Vanguard as a municipal bond trader, before working as a bond index trader.

Rising through the ranks, he became the head of bond indexing in 2013. He likes to keep a low profile, rarely appearing on TV or social media.

Last year, his $92 billion Vanguard Total Bond Market exchange-traded fund (ticker BND), lured $14 billion to become the world’s largest bond ETF.

Barrickman said he expects ETFs to attract a bigger share of passive inflows in the years ahead on account of their cheaper cost structure and the ability of investors to trade them in real time, like stocks.

Ironically, the increasing penetration of passive investing in the bond market has come as active managers have had some of their best years in recent memory relative to their benchmarks.

Over the past five years, 65% of actively managed bond funds tracking the Bloomberg USAgg Index have outperformed the gauge, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The analysis includes 72 funds with assets of at least $1 billion.

“Far too much money has gone into passive indexation both on the equity side and the fixed-income side,” said John Davi, chief executive officer at Astoria Portfolio Advisors. “Active management in the bond world actually makes sense, because you have more opportunity to pick and choose your credit and to make calls on interest rates and duration in order to outperform.”

Barrickman agrees that there’s a place for active funds in fixed-income investing, even as passive products continues to eat away their market share.

“We’re not anti-active, we’re anti high-cost,” Barrickman said. “Good low-cost active options, those absolutely have a place. The ETF structure itself has a lot of momentum and adoption.”

--With assistance from Katie Greifeld and Michael Mackenzie.