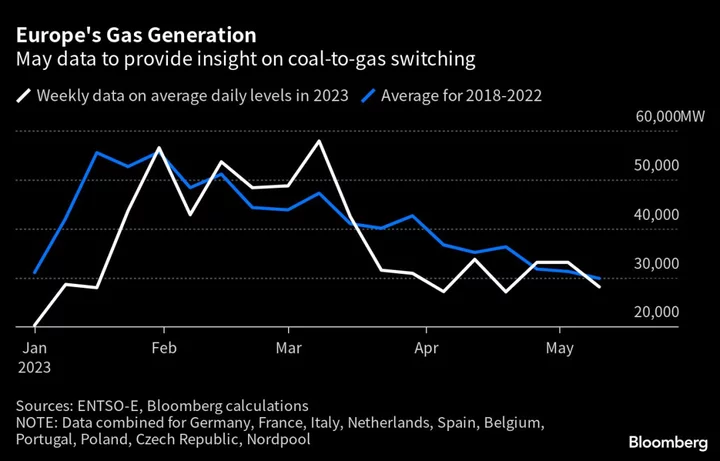

Traders are seeking buyers for piles of unused coal before it becomes worthless after the fuel was hoarded to save Europe’s economy from running out of power last year.

As concern over energy shortages eased following the continent’s mild winter, imported thermal coal started to be re-loaded at European harbors for markets such as Morocco, Senegal and Guatemala — a reversal in the fossil fuel’s usual flows.

All told, 1.12 million tons have been shipped out of Europe from Spain, the Netherlands and other ports this year, including a cargo of more than 145,000 tons to India in April. Smaller shipments have been sent on routes that would have been improbable in recent years.

“Some of this coal has been lying there for more than a year, and storage is precious,” said Guillaume Perret, a coal market analyst at Perret Associates. After sitting open to the elements for months in outdoor storage, coal starts to degenerate and eventually becomes unusable.

The dynamic shows the ripple effects of Europe’s energy crisis after the continent implemented emergency measures to counter the Kremlin’s moves to slash gas supplies. As mothballed coal plants were brought back into service, traders jumped at the chance to buy fuel — much of it from Russia — to produce the continent’s electricity.

But an influx of liquefied natural gas and mild winter temperatures meant most of it wasn’t needed. In the end, the European Union actually burned 11% less coal compared to the previous winter, according to think-tank Ember.

The turnaround from scarcity to glut has caused prices to deliver coal to the ports of Amsterdam, Rotterdam and Antwerp to tumble to just $90 per ton, less than a quarter of last year’s spike.

After running mines at full throttle and redirecting coal away from domestic power generation, suppliers as far away as Colombia, South Africa and Indonesia flooded Europe. Buyers were willing to pay a premium to keep the lights on — ignoring climate targets in the process. That same coal is now heading to new destinations.

“What is very unusual is to see flows from the Netherlands to Morocco and Spain to India,” said Alex Claude, chief executive officer of analytics firm DBX Commodities in London and a former coal trader. “It’s a sign there’s less demand down the Rhine and more outside of Europe.”

Selling on coal imported at sky-high prices into a depressed market may seem like a loss-making trade. But some who locked in prices using swaps, or cashing in on hedging the so-called dark spread, may still make a tidy profit.

The swaps involve securing revenues on the imported coal with counterparties, while utilities may pocket the difference from advance contracts sold for the power their coal was supposed to produce and paying current cheaper prices for the electricity.

The outflows are also a small supply boon for coal-hungry India and China, which on its own accounts for more than half of global consumption of the fuel. Despite analysts dialing down expectations of China’s economic recovery, the country is on track to import a record of 360 million to 380 million tons this year.

For Europe, the rush to re-load coal isn’t without risk. Last winter, Germany extended its last three nuclear reactors to help as a stop-gap, but those are now closed. And gas supplies are more dependent on pipelines from Norway and securing LNG cargoes on the global market.

“People need to be careful not to get too carried away,” said Perret. “We don’t know what will happen next winter.”

--With assistance from Thomas Gualtieri.

(Updates with China coal imports data in 12th paragraph.)