Peru — Latin America’s fastest growing major economy this century — is facing what was once unthinkable: a technical recession at a time of global growth.

The Andean nation’s economy has contracted 0.5% in the first five months of the year, stunning economists and defying the government’s position that “Peru is back” after a period of intense political turmoil.

“Beyond the concept of a technical recession, the government needs to recognize that Peru is not back, and we are facing a downward trend,” said David Tuesta, a former finance minister, who now heads the Peruvian Competitiveness Council, a private think tank.

It’s all but impossible to see a positive turnaround in the next month, economists said, which would confirm a technical recession, usually defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth.

At the heart of Peru’s unusual struggles is a double blow: political troubles carried along for years have finally caught up to its economy, and the El Nino weather pattern has paralyzed its important fishmeal industry. It’s bad news for President Dina Boluarte, who is facing record-low approval ratings seven months into her tenure.

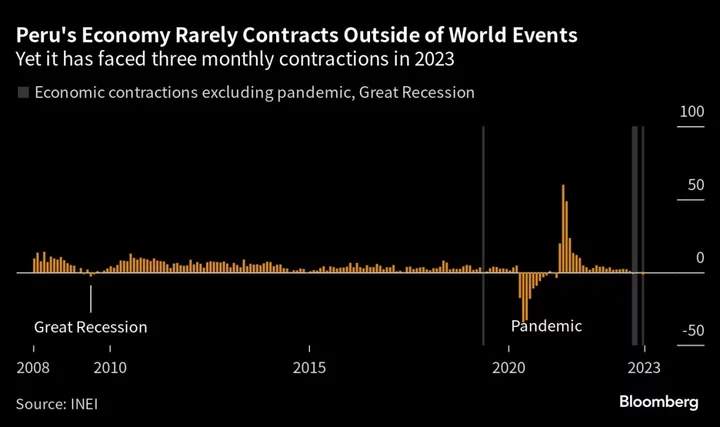

Peru emerged strong from the Great Recession and rebounded quickly from the pandemic. Excluding those two world events, Peru had posted only one single monthly contraction between 2008 and 2022. This year it has posted three monthly contractions.

Years of political turmoil have chipped away at the nation’s success story. Six presidents have cycled through office in seven years. Its latest presidential transition was its most traumatic, after ex-President Pedro Castillo was impeached and arrested. Boluarte’s presidency triggered thousands of Peruvians to boycott the economy through road blockades to demand her resignation.

She has held onto power but confrontations with law enforcement left almost 50 civilians dead.

Read more: Impeachment Mania Unravels an Economic Miracle in Latin America

The weak economy comes as Peru’s most vulnerable are also hurting. Poverty levels have skyrocketed, and more than 1 million Peruvians are now poor compared to a decade ago.

“It’s a strong reality check,” said Andrea Casaverde, Andean Economist at UBS. “It really confirms that the forecasts from the finance ministry and the central bank are materially very difficult to achieve.”

Peru’s finance ministry and central bank had forecast growth of 2.5% and 2.2% for this year, respectively. The finance ministry declined to comment for this story but said Finance Minister Alex Contreras would address the economic situation on Monday morning. Contreras has in the past wrongly predicted that the economy was rebounding.

Economists don’t see the technical recession carrying on for long, and Peru should see a small amount of economic growth this year.

What’s helping buffer the fall is Peru’s strong mining sector. Anglo American Plc opened its $5 billion Quellaveco mine late last year, providing significant additional copper production when compared to a year ago.

“You have that statistical event that doesn’t make the economy look as bad it should,” said Alonso Segura, a former finance minister and economics professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. “The economy is very weak.”