The UK’s offshore wind energy plans, and the climate goals that go with it, have been brought to a sudden halt.

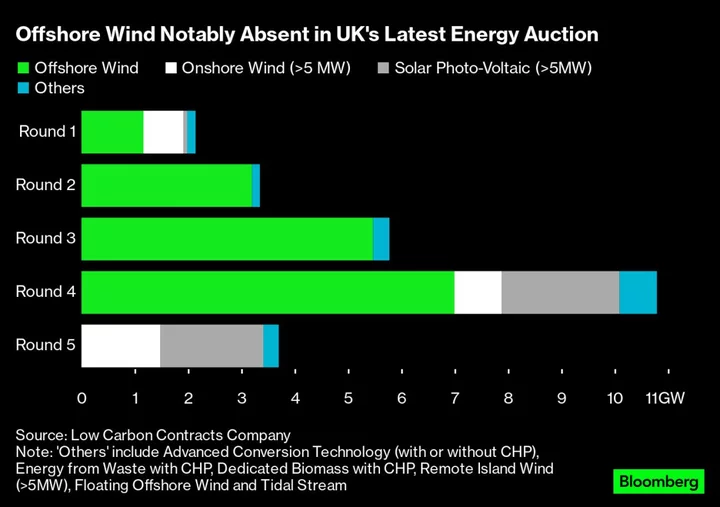

On Friday, an auction for contracts to build new wind farms received zero bids from developers. It’s the first time that’s happened since the current system was introduced almost a decade ago, and it raises major questions about the UK’s environmental targets.

The aim of the subsidies is to ensure a guaranteed price, but firms say it needs to be much higher or the construction of new wind turbines at sea will grind to a halt.

The dilemma for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is how to find a fix without spending too much money or pushing up energy costs for households. It’s pitting the short-term political cycle — an election is due by early 2025 — against the long-term need to address climate change.

Anything that increases bills will be a hard sell to voters still reeling from the worst cost-of-living crisis in decades, particularly if the optics include handouts to power companies. But with Sunak’s commitment to net zero already being questioned, accusations that the Conservatives have allowed a successful UK industry to fail would also be damaging.

This is “a major setback at a critical time when we should be looking to accelerate renewables,” said Simon Virley, head of energy and natural resources at KPMG.

Britain is the second biggest market for offshore wind in the world, behind China. Its success has come from the rapid reduction in the cost of the technology as projects have scaled up.

But the industry has been warning more recently that inflation pressures and soaring costs for raw materials mean that the declining cost curve can’t continue forever.

The UK desperately needs to fix the current situation if it’s to have any chance of meeting its offshore wind energy targets. It aims to have 50 gigawatts of power by 2030. There will be just over 15 GW at the end of this year, less than a third of its goal, according to BloombergNEF.

Ashutosh Padelkar, senior research associate at Aurora Energy Research, said the government needs to get 10 GW of offshore wind at its next two auctions to ensure that its target can be met. The highest in any auction so far has been 7 GW.

Friday’s blow effectively means a missing year for offshore wind development at a crucial time. On top of that, projects in the previous auction are being put on ice because rising costs.

In July, Vattenfall AB, a winner of last year’s auction, shelved a 1.4-gigawatt wind farm, which would have provided power for 1.5 million UK homes, saying the development is no longer viable after costs soared as much as 40%. Orsted A/S Chief Executive Mads Nipper has warned that its huge Hornsea-3 project, which also won a contract in 2022, is at risk.

The UK is aiming for a carbon free electricity grid by 2035, ambitious even before this week’s disaster. Tom Glover, UK country chair for German power company RWE AG, said such targets are “unlikely to be met without decisive government action.”

“Our industry needs the certainty of stable, future contracts for difference auction rounds based on sustainable pricing, separate pots for offshore wind, and realistic assumptions,” he said.

Read More: European Renewables Hit Three-Year Low as Wind Malaise Deepens

If power developers were looking for positive signs from the government, there wasn’t much to cling to in an initial statement from the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero.

It highlighted the results in the solar and onshore wind auctions, and merely noted the lack of offshore bids was “in line with similar results” elsewhere in Europe. It added that it will review its approach before the next auction, without any details.

Pricing System

Under the Contract for Difference auction system, the government sets a baseline price for the power generated. Companies have to pay anything in excess of that level back to the Treasury, while they get compensated if electricity market prices fall below.

Because developing offshore wind projects is extremely capital- and labor-intensive, securing a guaranteed government contract can help with funding.

The other option is for developers to use power purchase agreements with large consumers like manufacturers or data centers to guarantee revenues. This is seen as more risky because markets are volatile and companies want long-term contracts.

Some in the industry want the government to call time on the CfD auctions, saying they’re no longer fit for purpose. The Energy Systems Catapult, part funded by the government, says they are making the shift to net zero harder because they create a “winner-takes-all market,” leaving other developers without a route in.

A slowdown in offshore wind will mean “the big losers are UK industry and consumers, who will continue to pay high power prices for years to come,” said Eirik Hogner, partner and deputy portfolio manager at hedge fund Clean Energy Transition LLP. “The fix is extremely easy and quick; re-run the auction and let the market set the prices. I doubt that the UK government will act quickly however.”

Author: Rachel Morison, Priscila Azevedo Rocha and Jessica Shankleman