Wall Street banks have made “no significant moves” away from London’s dominant clearing service since Brexit, raising concerns of a risky dash into the European Union as it continues to push for more of the business to move into the bloc.

Klaus Lober, the first chair of the clearing counterparties supervisory committee at the European Securities and Markets Authority, said banks need to act to avoid “uncontrollable, unmitigated systemic risk.”

“If there is a shift it’s likely to happen quite quickly because nobody wants to be a first mover,” he said in a recent virtual interview. “But at the same time, if a movement comes, everybody wants to be on the train.”

Clearing trades is a core part of the financial system and one of the most contentious changes facing the City of London following a Brexit deal that made little provision for cross-border finance. Clearinghouses such as London Stock Exchange Group Plc’s LCH operate at the center of markets, collecting collateral from both sides of a trade to shield the wider system from a default.

ESMA wants banks to clear more European derivatives inside the bloc, though the timetable has slipped, and in recent months the regulator has suggested that 2025 won’t represent a hard stop for London. Global banks, which have moved hundreds of staff and portfolios into the bloc and expect to do more, are awaiting clarity. Some other elements of the market, meanwhile, have shifted into New York.

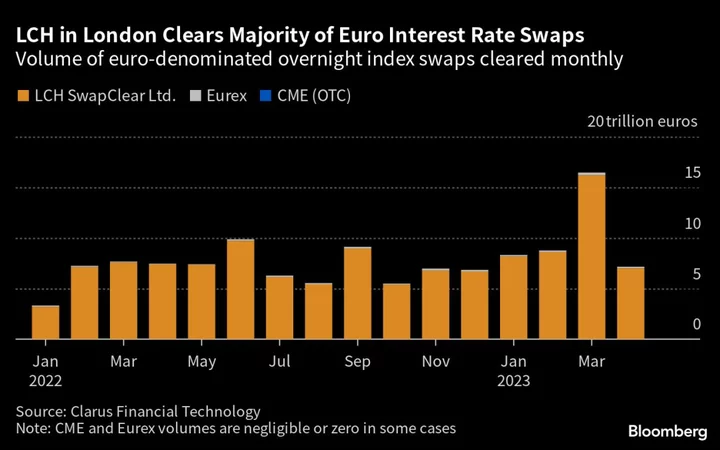

The watchdog is particularly concerned about slow progress in euro and zloty-denominated interest-rate swaps and euro-denominated short-term interest-rate contracts. In the first half of 2022 there was a notional €105 trillion ($116 trillion) worth of euro-denominated interest-rate swaps outstanding, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements.

The majority are cleared by LCH SwapClear in London, which in April processed about €7 trillion of the securities, dwarfing the volumes cleared by CME Group Inc. and Deutsche Boerse AG’s Eurex Clearing, according to data from Clarus Financial Technology.

A person familiar with the situation at one bank said there has been no formal mandate from the EU to shift liquidity from one venue to another and no formal deadline. Banks typically follow clients’ choices on where to clear their over-the-counter derivatives, an executive at another firm said. They asked not to be named as they are not authorized to speak publicly.

Representatives for Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Citigroup Inc., JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp. declined to comment. These banks are among the largest US firms shaking up their operations across Europe to ensure they can keep serving clients in both London and the EU.

The Commission has extended the UK’s temporary right to clear trades from the bloc while also looking to increase the capacity of its own clearinghouses such as Eurex and Euronext NV’s clearing service.

Lober said European clearinghouses needed to make themselves more attractive, and bank regulators should consider how to treat risks from lenders’ exposure to clearinghouses outside the EU.

He added that clearing of euro-denominated repurchase agreements and credit default swap transactions had shifted, and other positions could follow suit. “Current levels of exposure of EU entities in certain product categories create risks that may not be fully mitigated with the tools available to EU authorities,” he said. “This is why ways to reduce the levels of exposure are contemplated.”