To be a US retail worker in 2023 means fielding an onslaught of growing American anxieties about everything from high prices to politics. Increasingly, some workers say the job isn’t worth the wages.

Low pay, erratic schedules and monotonous tasks have long been a challenge for the nearly 8 million Americans working in retail, but the pandemic years have added a host of taxing new duties. Employees must cope with an uptick in shoplifting and customer orneriness. They manage online orders and run up and down the aisles to unlock items as quotidian as toothpaste.

A 2022 McKinsey study found that the quit rate for retail workers is more than 70% higher than in other US industries. And the Covid years made the problem worse. Before 2020, turnover for part-time retail employees — who make up the bulk of the in-store work force — hovered around 75%, according to data from Korn Ferry. Since then it’s shot up to 95% and hasn’t budged, which has at times led to understaffed stores.

“They expected so much,” says Henry Demetrius, speaking about his bosses at a Walgreens in Brooklyn, New York, where he worked as a customer service associate for a year.

Demitrius, who was 17 when he was hired, spent his days toiling as cashier, janitor, shelf stocker and passport photo taker. At times, it seemed he might have to provide security, too.

One time a visitor came in and demanded all the electronic items behind the counter, keeping his hand in his pocket like he had a gun. Demetrius did as he was told. The guy grabbed the gear and walked out of the store without paying. “I was like, wait, did I just get robbed?” Demetrius said.

It was the weight of these things that eventually drove him out of the minimum-wage gig in 2021. “I had to quit and take a break from working for like a year just to regain the ability to breathe and to focus,” he says.

Kris Lathan, a spokesperson for Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc., says “safety and security of our patients, customers and team members is our priority.” The company also offers mental health and wellbeing support, including free counseling sessions, Lathan says.

The declining worker experience follows a tough decade for retailers. Stores that survived the “retail apocalypse” have had to find ways to cut costs and boost profits with fewer shoppers. For many, particularly small brands, that has meant reducing headcount, or finding other ways to bring in money. Physical locations increasingly double as returns and logistics centers, as companies build out hybrid online and offline services. The early years of the pandemic brought a slight respite, as people stuck at home spent their time — and stimulus checks — on online shopping. But that quickly gave way to supply chain issues that snarled inventories and the era of high inflation.

Amanda Sukhdeo, a 20-year-old cashier at a children’s clothing store in the Bronx, New York finds herself frequently struggling to reason with parents unhappy with the price tag. “Sometimes customers are understanding about it,” she says. “Sometimes, not so much.” She can’t help but empathize as she rings up purchases and sees how much they’re paying. “In my head, sometimes, I’m like, oh wow, this is crazy!” Sukhdeo says.

Much of this isn’t unique to the US. Retailers all over have struggled to adapt to new shopping habits and ebbs and flows in the economy. Cost-of-living crises have led to reported rises in abusive shoppers and crime in the UK, Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand. Staff are unhappy: A recent survey of managers in the UK found absences on the rise. But US workers tend to have fewer job protections and benefits, and less leverage to improve their working conditions.

To hear rank-and-file retail employees tell it, working conditions started to deteriorate when they returned to the job after mandatory Covid lockdowns. Customers didn’t particularly like being told to wear masks or forgo free samples. But as health and safety protocols eased, tensions didn’t.

“You’re just kind of at the mercy of customers and however they’re feeling,” says Adam Ryan, who works at a Target in Virginia.

Nearly four out of five companies have seen a rise in “guest-on-associate violence” over the last five years, according to the National Retail Federation, a trade group. Large retailers say their annual apprehension of shoplifters climbed by more than 50% in 2022, according to a survey by Jack L. Hayes International, a loss prevention consulting firm headquartered in Wesley Chapel, Florida. Dick’s Sporting Goods, Nordstrom and Dollar Tree all played up theft in recent investor calls.

And in today’s era of political polarization, some have been caught in the crossfire of the culture war — most notably at Target Corp., which pulled some LGBTQ-themed merchandise from its shelves earlier this year after employees were subjected to what CEO Brian Cornell described as “gut-wrenching” threats from certain customers. “Violence in stores for political reasons is something that we didn’t really experience in the past,” says Stuart Appelbaum, president of the 100,000-member Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.

Target declined to comment.

Early on in the pandemic, workers say they didn’t feel equipped to deal with their changed environment. On Christmas Eve in 2020, Sarah Doherty was working the register at an American Eagle in Lynnfield, Massachusetts, when a man walked into the store and bought a pair of khakis. He returned soon after saying they didn’t fit. Because of Covid-19, he was told, the store wasn’t taking returns. Maybe he hadn’t seen the sign by the door warning of the policy?

The customer started screaming at Doherty, venting his frustration not just about the policy but the pandemic itself. The shopper finally left, but not before nearly getting into a fight with another customer in the checkout line who tried to calm him down. Doherty was shaken. “I was only an 18-year-old girl,” she says. “It was just a little stressful having a man yell at you on Christmas Eve.”

Alissa Heumann, a spokesperson for American Eagle Outfitters Inc., wouldn’t comment on Doherty’s experience but says, “We are committed to the health, safety and wellbeing of our associates.”

Doherty now works at a smaller retailer where she’s been provided with de-escalation training, which has made it easier for her to handle unhappy shoppers. “The first day I was there, they talked us through the best ways to calm down customers when there’s a problem,” Doherty says. “That’s definitely important.”

That kind of training has become more widespread, but Patrick Fennell, an assistant professor of marketing at Kennesaw State University, has found that less than 65% of lower-level-employees have received such instruction. That compares to 82% of managers.

“The majority of the folks we talked to were in the lower levels,” Fennell says. “They were not really familiar with how to adequately handle these situations.”

Workers, for their part, are conflicted about their role. A 2023 study of frontline retail workers co-authored by Fennell found that 89% have negative feelings about stepping in when customers are behaving badly.

“You know, that’s kind of like the basic cardinal rule: The customer’s always right and don’t upset them, otherwise you’re gonna have trouble with your management even if you know it’s not your fault,” says Ryan, the Target worker.

On the other hand, Fennell says, some workers are frustrated when they are forbidden from intervening.

Artavia Milliam, who works at an H&M in New York’s Times Square, has pretty much seen it all. She watched a shoplifter shove one of her co-workers when he asked the guy not to steal items from the store. A manager has had a knife pulled on him when he tried to do the same. Milliam herself has been cursed out by a customer whom she asked to remove a drink from a clothing display. The shopper later apologized, saying she’d been having a bad day.

She’s also regularly fielding customer complaints about how much the store’s prices have risen, thanks to inflation. “All we can say is, hey, everything went up,” she said. “We don’t set the prices.”

Milliam says the most unpleasant development is that some customers began relieving themselves in the store’s fitting rooms. “That’s pretty much post-pandemic,” she says. “It wasn’t much of an issue before.” Milliam says she and her co-workers complained to their union, the RWDSU, which got H&M to bring in an outside firm to clean the rooms instead of relying on store employees to do it. H&M declined to comment.

Milliam and her fellow employees, however, are hardly the norm in the US. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 5% of retail employees were represented by a union in 2022. That’s a much smaller share than in many European countries, where wages are higher and retail workers are more likely to have health insurance.

Yet as their working conditions grow more difficult, US retail employees are warming to the idea of union representation. “The pandemic opened people’s eyes,” says the RWDSU’s Appelbaum. “It’s never easy, but people feel that organizing is more necessary now than they realized before in order to protect themselves at work.”

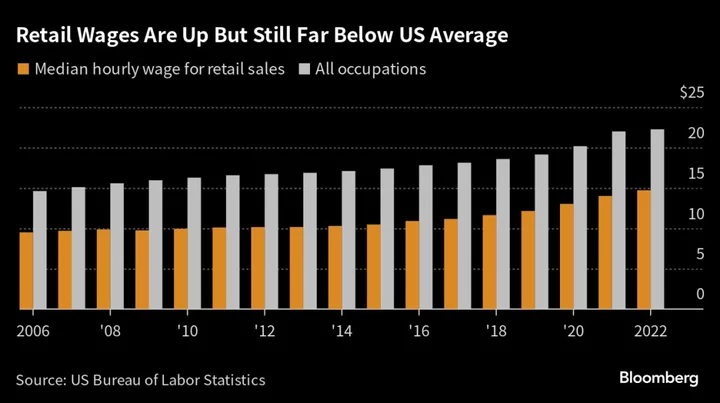

Retail wages are rising slightly faster than those in other industries, but retail employees still get paid a lot less than the median US worker. From 2006 to 2022, the median wage for retail salespeople rose 55% while US workers overall saw a 52% gain. Since 2019, retail wages are up 21%, compared with a 16% gain overall.

Still, inflation has eaten a lot of that away, leaving workers questioning whether it’s worth it to deal with such headaches when they’re only making minimum wage. (An exception is Milliam, who has worked at H&M for 13 years and says she’s doing better thanks to her union — although she laments that inflation is taking a bite out of her paycheck, too.)

Yorlenny Morillo, 28, has worked for a variety of retailers in the New York City area ranging from thrift stores to national chains. “I can’t stress enough how much I actually do love the work,” she says. “I don’t mind fixing racks all day. I don’t mind dusting a store.”

But Morillo has often worked for minimum wage and has had difficulty getting enough hours to get by. She says it helps that she lives with her partner who has a higher-paying job at Cole Haan. Things are looking up for her, though. Morillo recently got a job at a Staples in Brooklyn, and she says it’s the first time she’s been offered health-care coverage. Up until now, she’s been on Medicaid.

--With assistance from Ella Ceron and Alexandre Tanzi.