Britain’s young families and low-to-middle earners in the Millennial generation are shouldering the heaviest burden in the Bank of England’s effort to curb inflation.

A long-term shift in home ownership has left a smaller group paying the biggest price for higher interest rates, a Bloomberg analysis of official data shows, as markets brace for the central bank to raise borrowing costs for a 14th consecutive time next week.

Concentrating the squeeze on millions of young families, Londoners and middle income people typically in their 30s and 40s could be politically perilous for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak ahead of a general election expected next year. Households are making difficult decisions as their loans come up for renewal at a time when the cost of a two-year fixed rate mortgage is close to a 15-year high.

Andrew Willshire, a London-based analytics consultant, is planning to work more to make up for a hefty increase to his monthly repayments when he renews his loan in October. He places blame on the BOE.

“I’m feeling a bit raw from being one of the 20% of people that’s actually having to shoulder the burden,” Willshire said. “The number of people that actually have mortgages is quite small... I’m definitely keeping track of spending, not taking any commitments or booking holidays.”

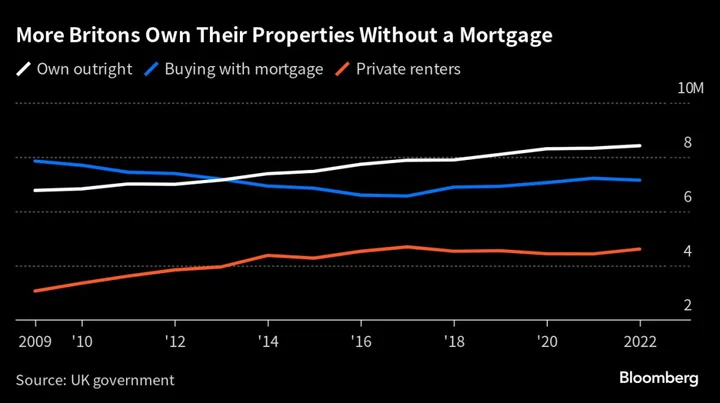

The cycle of rate hikes that began in 2021 is unique because the number of people who own their own home outright has surpassed those who are paying a mortgage linked to their property.

Just 26% of English households are mortgage holders, down from 32% in 2012 and well below the 37% that now own outright, Office for National Statistics data shows. Many private renters, mainly in their 20s and 30s, are also bearing the burnt as landlords pass on higher mortgage costs to tenants.

Those figures shed light on the winners and losers from the quickest increase in borrowing costs in three decades as policy makers led by BOE Governor Andrew Bailey respond to the worst bout of inflation in the Group of Seven nations. It’s opened a debate at the BOE about how much higher rates need to go to control inflation — and who will feel the pinch most.

Rob Setters, who along with his wife is a physiotherapist, is another bracing for higher rates. He and his wife are facing an increase in monthly payments of over £600 ($778) when their current mortgage deal expires.

“My wife’s going to be on maternity leave, which is going to drop her income, so we need to save up,” said Setters, who is based in Surrey. “I keep on budgeting our monthly outgoings and it’s only just positive, and that’s without much luxury spending, so no holidays or going out for meals.”

About 4 million households will pay more when they refinance their mortgage deals by the end of 2026, on top of 4.5 million who have already been squeezed. But many older Britons and savers are insulated from higher rates and some even stand to benefit.

“It’s predominantly younger generations and those who have bought a home most recently who are likely to be most impacted by higher rates,” said Aneisha Beveridge, head of research at the estate agent Hamptons International. “Most of them will find it a painful adjustment.”

More than 3 million families with children still at home are being hit by the building mortgage squeeze, the Bloomberg analysis shows. Those on middle incomes and in their 30s or 40s are also worse affected. Families with children amount to more than four-in-10 mortgage holders, and a couple with dependent children is the single biggest category affected.

Londoners are also more likely to feel the squeeze, since far fewer people there own their home mortgage-free than in the rest of England. They also pay higher costs on loans for buy-to-let properties, which are being passed on to an increasing number of renters.

For the BOE, that means the channel through which mortgage costs affect the economy is more concentrated and potentially less potent because it works through a smaller group of people. However, this is partially offset by many renters having mortgage pain passed onto them by landlords.

Britain’s intensifying mortgage squeeze threatens to tip an already stagnant economy into recession and deepen wealth divides that cut across generations and incomes.

“We were basically in a position where we were extremely narrowly avoiding recession to begin with, so there has to be a high chance that the additional high rate mortgage pain pushes us in that direction,” said James Smith, research director at the Resolution Foundation.

Research by Resolution finds that the share of households with a mortgage increases with incomes. More than half of the top earners have a home loan.

However, the biggest increases in mortgage repayments as a proportion of income is among low-to-middle income households. Between the end of 2021 and end of 2026, annual repayments will have jumped by 6% of income for mortgage holders in the second-income quintile, compared to 3% for the top fifth of earners, the think tank said.

Renters, as well as homeowners, are feeling the pinch as their landlords seek to recoup higher mortgage costs by raising rent. Anthony Nesta, a father of two from Nottingham, said the rent for his two-bedroom terrace house has more than doubled.

“About three years ago, I was paying just over £500,” Nesta said. “Now, for the same house — no improvement, nothing — I’m paying £940. After Covid and the the Ukraine war, the rent started going up. Those have been the excuses.”

To cope, the 42-year-old plant operator and his family have had to “cut down to bare minimum.”

“We’ve seen in the last year 300,000 renters who’ve been forced from their homes by an increase in rent, and that has a really huge psychological impact,” said Beth Stratford, a spokesperson for the London Renters Union.

Last month Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt ruled out financial help for those suffering from the mortgage squeeze, saying he won’t do anything that would prolong inflation.

Nonetheless, some believe targeted help should be provided to ease the pain on the hardest hit households.

“Vulnerable homeowners and renters urgently need help,” said Rose Grayston, an independent housing policy consultant. “What’s needed is targeted support for those at real risk of financial distress and homelessness, not a blank cheque.”