The UK is likely to sell fewer bonds than initially planned this fiscal year after higher tax revenues gave an unexpected boost to the government’s finances. The reduction will particularly affect long-dated debt.

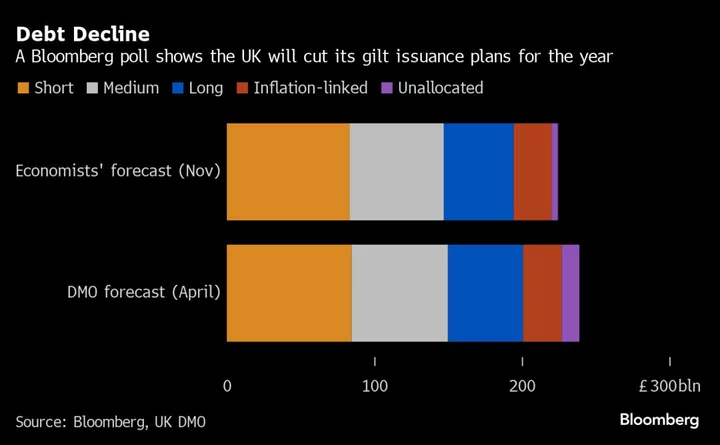

The Debt Management Office is expected to announce a gilts issuance target of £224 billion for the current fiscal year, according to a survey of 13 banks polled by Bloomberg ahead of Wednesday’s Autumn Budget. That represents a 6% drop from the £237.8 billion plan announced in April.

The cut in gilts sales comes as the UK has consistently reported stronger fiscal data, due to higher tax revenues, including VAT and income tax. This has boosted total government revenues so far this financial year by 5.6% from a year earlier, and 3.3% above a forecast by the Office for budget Responsibility, reducing the nation’s borrowing needs through April 2024.

“The latest public finances data painted a materially better picture for borrowing,” Sanjay Raja, senior economist at Deutsche Bank wrote in a note. “Higher receipts have resulted in a significantly lower borrowing path.”

The bulk of the reduction will come through gilts maturing in 20 years or longer, analysts say, due to weaker demand from domestic pension funds, which reduced buying of long-dated debt since last year’s LDI crisis.

Gilts with maturities of up to seven years will account for about 37% of borrowing, according to the survey. That compares to 36% in the April plan, with the rest accounting for medium- and long-dated bonds, and inflation-linked debt.

Respondents of the survey also see an increase in the contribution of bonds issued to retail investors through the National Savings & Investment program, which has seen a surge in demand due to high interest rates.

“Pension funds just don’t need to buy as much duration as they have in the past,” said Imogen Bachra, head of UK rates strategy at NatWest Markets. “The shift toward the shorter maturity buckets is the DMO’s response to that.”

Slowing demand for the longest-dated debt has not gone unnoticed by the DMO, with chief executive Robert Stheeman saying earlier this year that demand from the pension industry was “beginning to shift shorter.”

Waiting for Cuts

The expected borrowing reduction doesn’t take away from the fact that UK debt has risen sharply in the past few years, with net debt reaching a record 103% of GDP this fiscal year, according to DMO data. Debt issuance is still expected to be about a third higher than last year, and the government has signaled that borrowing will continue to climb in the coming years.

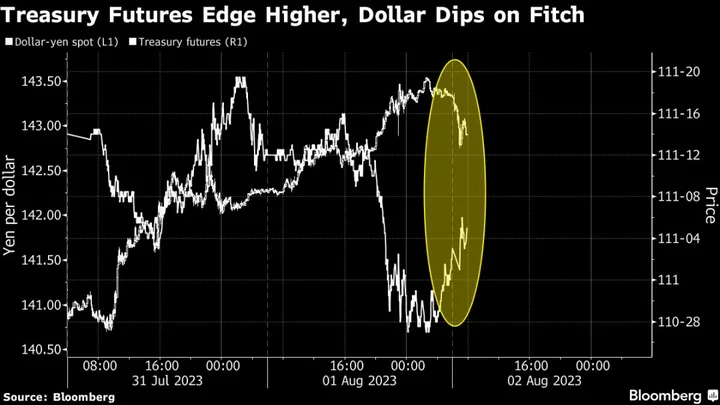

A smaller issuance could be a sign that the DMO is holding off from selling more bonds at current interest rates because they may fall next year. The Bank of England is expected to cut official borrowing costs by 75 basis points in 2024, partially reversing its fastest tightening campaign since the 1980s, which has sent gilt yields to their highest since the global financial crisis.

“It makes more sense to do a little bit more short-dated debt that might roll off onto cheaper debt in two or three years’ time, rather than locking in these yields we’ve seen on 30-year debt,” said Bachra. The yield on 30-year gilts soared to its highest since 1998 last month.

Countries including the US have tempered longer-dated issuance plans as concerns about strong supply have weighed on the notes. The UK could adopt a similar path, said Megum Muhic, a rates strategist at RBC Europe.

The DMO “wouldn’t want to flood the market and cause a repeat of what happened during the Truss government,” Muhic said.

--With assistance from Anchalee Worrachate.