The UK government is desperate to find a way to make child care more affordable and encourage more women back into the workforce. Yet tens of thousands of families had an alternative before Brexit that barely exists today.

Au pairs used to be the answer to several dilemmas. They provided child care at a reasonable price, flexible help around the clock, and a way for young people to learn new languages and experience a different culture. But few industries have been hit in the same way by the withdrawal of the UK from the European Union in Jan. 2020. Some agencies report that business has collapsed by as much as 95%, with stricter immigration rules for European citizens leaving families with few other options. It’s widely reported that families, especially women, have reduced their working hours to take on more child care duties due to the high costs of nurseries.

Pre-Brexit, there were estimated to be up to 90,000 au pairs in the UK at any one time. Many came from around Europe; a survey by the British Au Pair Agency Association in 2020 found that more than half came from just four countries in the continent. But the route into the UK for many such au pairs has dried up. Now, positions are available only to a small group of people including those who have already spent enough time in the country to qualify for settled or pre-settled status. There is also the Youth Mobility Scheme visa which allows some people aged 18-30 from a select group of countries including Australia, New Zealand and Canada to work in the UK for up to two years.

This hasn’t attracted nearly enough to match previous supply, according to Sandra Landau, owner of the Childcare International au pair agency. She estimates that the lack of candidates since Brexit means her business has dropped by 95%. She no longer has any European candidates at all.

Referring to the government, Landau, who has had to make her four permanent members of staff redundant, said: “It could be solved so easily if they could just give Europeans the right to use the Youth Mobility Scheme.” A spokesperson for the Home Office said the government doesn't plan to introduce a visa route for au pairs.

Read More: One in Four British Parents Quit Jobs or Education Because of Child Care Costs

It’s not just her agency that has collapsed. Landau was the founding chair of the British Au Pair Agencies Association (BAPAA), a trade body for the industry. At its peak around a decade ago, Landau estimates that it had up to 37 member agencies, which met at bustling annual conferences and formed a close-knit, if sometimes competitive, community. Today it has just five members left, with the majority giving up due to lack of candidates.

To be sure, only those who have spare rooms in their homes could rely on au pairs in the first place but they can be a very cost-effective option. The government suggests that they should be given at least £90 or more in “pocket money” a week and offered free accommodation and meals in exchange for around 30 hours of childcare. That’s far below the £14,000 annual average cost to have one child in nursery or after school clubs. According to a 2020 survey by the British Au Pair Agency Association (BAPAA), 41% of parents said they would reduce their working hours if they weren’t able to use au pairs.

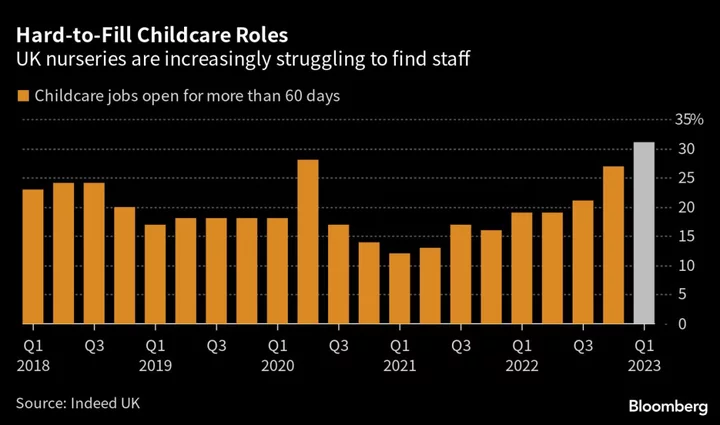

The reduction in availability of au pairs also comes as UK nurseries struggle to fill roles. The share of roles in the child care sector classified as hard-to-fill — meaning they were left open for two months — spiked to 31% from one in five in early 2022, according to data from job search platform Indeed. The overall difficulty in finding care that’s affordable puts under pressure the government’s pledge to make child care more affordable and encourage more women to rejoin the workforce.

Changes to immigration law also means that au pairs are less affordable than they once were, with offered allowances climbing up to £300 a week due to low supply, according to Tuuli Liiskmaa, director of Smartaupairs. A much smaller talent pool also means that au pairs have amore choice over who they want to work for (and the sorts of demands they can make); online adverts show some families offering au pairs not just a bedroom but an entire floor of their home.

As the au pairs in agencies’ books have gone down, families are turning elsewhere to find someone to look after their children — and it’s not always legal routes. On a string of Facebook groups for au pair matching, parents often get responses from young people as far away as Uganda or the Philippines asking for work.

Bea Glass, director of International Helping Hands Agency, said she is constantly battling these posts as an admin on a group with around 33,000 members. She doesn’t accept adverts from families who don’t mention au pairs needing the right to work in the UK, and deletes posts from any potential au pairs who come from countries that aren’t part of the Youth Mobility Scheme.

“Only this morning I noticed there were 10 posts of girls from the Philippines,” she said, adding that she believes “a lot” of families were taking on au pairs who had arrived illegally on tourist visas. “People get desperate and do silly things when you've got children,” she said.

--With assistance from Irina Anghel.

Author: Helen Chandler-Wilde