Britain dodged a recession last year despite a historic energy price shock and an investor revolt that forced out the prime minister. Recent data have raised questions about whether it will be so lucky this time around.

Surveys of purchasing managers and retailers both point toward a sudden slowdown in recent weeks. More companies are taking steps to address financial distress. Even the jobs market, which remained strong through the pandemic, is showing signs of weakening.

While such indicators will be read as signs that the Bank of England’s efforts to cool the worst inflation among the Group of Seven nations may finally be taking hold, they also bolster arguments that the country will have to suffer a downturn before policymakers finish the job. The data led traders to trim bets on further rate increases, fueling the biggest decline in 10-year gilt yields in five months.

“Something has definitely changed in the last few months,” said Kitty Ussher, a former UK Treasury minister now working as chief economist at the Institute of Directors, noting that a half-point rate hike in June sent “a big judder” through the economy. “I’m feeling less confident about the second half of the year.”

That’s bad news for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, who took power last year pledging to cut inflation and restore growth after opposition to a tax-cut heavy budget plan by his predecessor, Liz Truss, led her to resign. Sunak’s Conservatives are trailing the opposition Labour Party by double digits in advance of an election Bloomberg News has reported is penciled in for November of next year.

So far, the consensus among economists, including the BOE’s official forecast, is for stagnation rather than recession. As of Friday, output was expected to expand by 0.2% this year, according to the median estimate of 57 analysts surveyed by Bloomberg.

Still, some have been revising down their forecasts, especially after the unexpectedly large rate hike in June. Bloomberg’s own economists are predicting four consecutive quarters of contraction beginning in the final three months of this year, with a peak-to-trough decline of about 1%.

Such views have been bolstered by forward-looking indicators suggesting a deterioration in conditions since the BOE published its most recent forecast on Aug. 3. The monthly purchasing manager index unexpectedly contracted in August, falling to 47.9 from 50.8 the previous month. The measure had been above 50, a level that indicates expansion, since February.

What Bloomberg Economics Says ...

“The UK avoided recession in the first half of 2023. The sharp fall in the PMI between June and August has raised the downside risks. We have penciled in a quarterly decline in GDP in 4Q23. Further falls are likely over the first three quarters of 2024.”

—Dan Hanson and Ana Andrade, Bloomberg Economics. Click for the REACT.

Although the PMI similarly signaled a recession last year, that was largely driven by expectations that energy prices would persist at higher levels than they did in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The current contraction is being fueled by the BOE and Governor Andrew Bailey warnings that rates would have to stay “sufficiently restrictive for sufficiently long” to bring inflation back to the 2% target.

Prices are still increasing at more than three times that pace. Investors expect the central bank to raise interest rates by another 0.25 percentage point to 5.5% next month, pushing borrowing costs to their highest level since early 2008.

The UK’s slowdown follows bigger declines across the euro area, which saw its third consecutive monthly contraction in PMIs this week. Also looming in the background is a deeper slowdown in China, which the IMF had projected would drive more than one-third of global economic growth this year.

The UK delivered its strongest quarterly growth in more than a year in the three months that ended in June, in a surprising show of resilience. Consumer confidence also rebounded this month, market research company GfK said Friday, as inflation showed signs of cooling and strong wage growth buoyed household finances.

“If the UK could get through this cycle with a period of stagnation in growth or possibly even sort of mild contraction, we would be doing very well by the standards of the last 50 years,” said Ian Stewart, chief UK economist at Deloitte. “Perhaps we’ve all become a little bit too complacent about some of the downside risks.”

Higher interest rates are feeding through to mortgage costs, draining money from the pockets of consumers. The latest official retail sales figures showed a sharp drop in volumes. The value of goods purchased has risen sharply since the current bout of inflation started — meaning consumers are spending more to buy less.

A survey from the Confederation of British Industry indicated that August retail sales fell at the fastest year-on-year rate since March 2021, when the nation was in a Covid-19 lockdown. The outlook is for a further deterioration in the next three months, with retailers investing less and employing fewer people.

That’s starting to seep through into what so far has been a red-hot labor market, with more jobs advertised than candidates to fill them. The latest figures show Britain’s unemployment rate has ticked higher as vacancies dwindle and more people who quit working during the pandemic return to the jobs market. The gauge hit 4.2% in the second quarter, and 4.6% in June alone — the highest in more than two years.

Activity is also being weighed down by the worst run of strikes since the 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher was prime minister. Doctors, nurses, train drivers and criminal lawyers have all walked off the job in recent months seeking a pay that matches the swingeing inflation rate. Although Sunak’s government has settled with most public services workers, railway workers remain aggrieved and plan to continue strikes through the autumn.

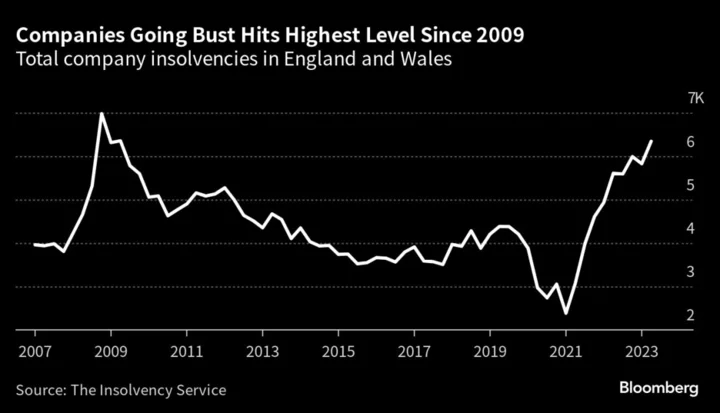

The spike in borrowing costs has increased the risk of corporate defaults as some medium and large companies struggle with debts. Almost 440,000 firms were already in “significant distress” in the second quarter, an increase of 8.5% from a year ago, according to consultancy Begbies Traynor Group. Many of those are in construction, where output of private new housing fell more than 8% year-on-year in June.

“We’re a little bit concerned about the additional impact of interest rates that are in the pipeline for mortgage holders that haven’t really been put through because they haven’t remortgaged yet,” said Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG in the UK. “We are still seeing more headwinds for consumers in particular.”

--With assistance from Andrew Atkinson, Eamon Akil Farhat and Dayana Mustak.