Sweden’s real estate crisis is raising echoes of a crash in the 1990s that sparked a full-blown financial meltdown, but government and central bank officials are betting they can keep the problems contained.

Even as slumping property prices and surging financing costs weigh on the Nordic country’s economy, authorities believe they can ride out the turmoil without widespread intervention. That leaves indebted landlords like Samhallsbyggnadsbolaget i Norden AB — commonly known as SBB — isolated as they battle to close funding gaps.

“You should always be prepared for the fact that crises can occur and be ready to act, but at the moment we don’t see that we are close to a situation like that,” Finance Minister Elisabeth Svantesson said on Thursday. “I don’t feel worried, but I see that there are risks.”

“I was a bit more concerned six months ago,” she added. “I feel that it may be going in the right direction now.”

With the banking sector better capitalized and less exposed to property debt than 30 years ago, officials see limited risk of spillover to the wider financial system. The view helps support efforts by Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson’s administration to keep tight reins on public spending to help bring down inflation. But getting the approach wrong could turn what’s expected to be a recession this year into a deeper systemic crisis.

The government’s stance is backed by regulators and lenders in the country. Swedish watchdog Finansinspektionen says bank profitability and capital buffers provide enough resilience to withstand a shock, even if risks of credit losses have increased. Swedbank AB Chief Executive Officer Jens Henriksson told Bloomberg this week that he’s “confident” in the credit portfolio of the bank — one of Sweden’s top three lenders — and sees progress in the measures taken by real estate companies.

“Inflation has to get back to the target and that will benefit the whole economy, including the real estate sector,” Riksbank Governor Erik Thedeen told Bloomberg. “Some may struggle on the way there, but there’s no alternative.”

Read More: Sweden Gives ‘Bleak’ Outlook for Economy Dogged by Inflation

International markets aren’t as confident though. Concern about the sector has contributed to pushing the Swedish krona to record lows against the euro, putting the country’s central bank in a bind. While policy makers would like to see the domestic currency strengthen to curb inflation, more rate hikes could increase pressure on the strapped real estate sector.

Alongside embattled SBB, there are concerns that companies like Heimstaden Bostad AB and a host of smaller landlords, which managed to raise cheap financing without public credit ratings, could run into financing difficulties.

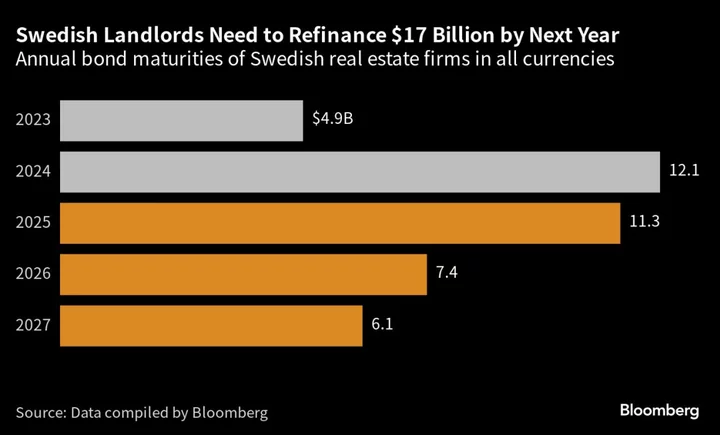

At the height of Sweden’s real estate boom in 2021, 65 Swedish property companies sold $27 billion worth of bonds, but those funding routes are now largely closed. The volume has slumped to just $2.1 billion so far this year and the number of issuers dropped to 17, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Several of those smaller companies have gone to bondholders in the past 12 months to ask for looser terms to avoid breaching covenants or worse. Examples include Sehlhall Holding AB, Oscar Properties Holding AB, Nivika Fastigheter AB and most recently Wastbygg Gruppen AB.

SBB remains the epicenter of the crisis. The company faces a fight for survival because of its high debt and failing to raise cash as quickly as other large landlords, such as Castellum AB and Fastighets AB Balder. After piling on debt to acquire a range of public-sector buildings from schools and police stations to nursing homes and social housing, Stockholm-based SBB has said it faces a shortfall of 8.1 billion kronor ($740 million) over the next 12 months.

Community property emerged as an asset class out of the 1990s crisis, which led to the government nationalizing banks and taking on bad loans after a housing bubble burst. Strapped local authorities subsequently looked to raise cash by selling buildings and leasing them back. SBB pursued this market vigorously after being founded be a former politician in 2016.

The company’s links to the public sector have rattled nerves, but Swedish school children are unlikely to be left without classrooms in the event of an SBB collapse. Instead, the company’s tenants, which tend to have long-term leases, would most certainly just pay rent to a new owner. Besides local municipality’s buying back properties, there’s enough investor demand for stable, tax-financed cash flows, and the low krona bolsters the appeal among international property buyers like Morgan Stanley.

Niklas Wykman, Sweden’s financial markets minister, sounded out market participants after SBB lost its investment-grade status in May. He concluded that there was sufficient interest in Swedish public-sector properties. On Monday, Fitch Ratings noted that the portfolio remains solid, even as it downgraded SBB five notches deeper into junk amid refinancing concerns.

“Of course there are contagion effects, but we still see them as fairly limited even if a single name ends up in serious problems,” Mattias Persson, chief economist at Swedbank, said in an interview. “We believe that there are owners and others who are on the outside that are ready to step in.”

Under Chief Executive Officer Leiv Synnes — who replaced SBB founder Ilija Batljan in June — the company has managed to buy some time, despite a spate of rating downgrades. It covered about half the near-term funding gap with deals including the sale of preference shares in a residential subsidiary, disposing stock in property developers JM AB and Heba Fastighets AB and agreements on property disposals.

But doubts remain. Talks abruptly ended in July with Canadian partner Brookfield Asset Management Ltd. over selling a 51% stake in a portfolio of education buildings, showing the challenge of closing deals in a volatile environment.

The company does have other options. The landlord is weighing a carve out of its entire residential portfolio worth 36.5 billion kronor, Bloomberg News reported earlier this month. A listing of Sveafastigheter Bostad Group AB, a residential property firm it acquired in 2020 for 2.8 billion kronor, could be another alternative.

Synnes said the strategic review is “on track.” Financial stability and liquidity are the top priorities in a process that includes exploring the sale of the entire company, he added.

“National government policy has no impact on our strategy,” the CEO said in an email response to Bloomberg questions. “I am confident in the actions we are taking to improve SBB’s situation and outlook.”

While the problems of indebted landlords has so far had limited impact on the Swedish economy, an abrupt slump in home construction has exacerbated the downturn. Forecasts indicate housing starts this year will be less than half of the 63,000 needed to keep up with demand, according to Sweden’s National Board of Housing.

“If no measures are taken this will not just be a temporary slump but a more protracted decline,” said Anna Broman, a housing policy expert at industry organization Byggforetagen. “The situation is very serious.”

Read More: Sweden Housing Starts Nosedive in Sign of Worse Shortage to Come

That’s putting pressure on the government to act. But the focus is on propping up strapped mortgage holders and easing strains on the construction industry, which represents about 11% of gross domestic product and employs almost 350,000 people. By contrast, overextended landlords are being left to deal with their problems on their own.

“There are clearly concerns in the real estate sector and not every company will figure it all out,” Claes Mahlen, chief strategist at Svenska Handelsbanken AB, said in an interview. “But we are unlikely to see anything reminiscent of the crisis in the 1990s.”

--With assistance from Love Liman.