In a Downing Street office last week, under the glare of chandeliers and a big television screen, a flash of frustration burst across Rishi Sunak’s face during a conference call.

The UK prime minister complained to close colleagues that his government never gets credit for making hard decisions in the public interest, two people present said on condition of anonymity. Sunak went on: he had picked up the pieces after his predecessor Liz Truss brought the UK economy to the brink of catastrophe, and his focus on fighting inflation was preventing disaster with little political upside, they said.

It was a rare unguarded moment for the usually upbeat premier — who also appeared below par at this week’s session of prime minister’s questions. Sunak is feeling the heat after a month that laid bare the parlous state of the UK economy, mired in persistent inflation, rising rising interest rates that are burning mortgage-holders, and the threat of recession.

This week brought further setbacks: the possible collapse of London’s water supplier and a court decision that found the government’s flagship policy to deport migrants to Rwanda was unlawful. Then Friday, just as Sunak was making a major health care staffing announcement, his climate minister quit, slamming the premier’s environmental record.

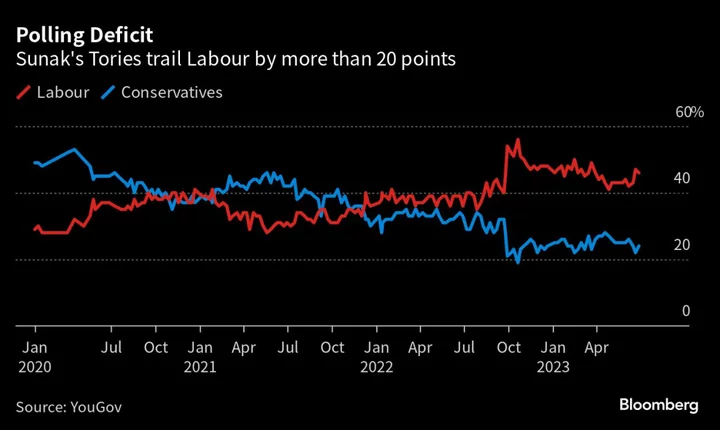

As the clock ticks down toward a general election due by January 2025, it’s becoming harder for Sunak to turn things around for his ruling Conservatives and upend Labour’s double-digit polling lead, which has increased to 22 points from 16 in three weeks, according to YouGov.

He’s asked voters to judge him on five pledges: to halve inflation, get the economy growing, cut the national debt, reduce National Health Service waiting lists and stop boats of asylum seekers crossing the English Channel. He risks failure in all of them.

One minister told Bloomberg that the premier is a fundamentally decent person trying to do the right thing for the country, with no reward.

Another insisted there’s no alternative to getting inflation down, a challenge faced by economies worldwide after the Covid pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine, even if it meant the pain of higher interest rates and a recession. Any responsible politician, including Labour leader Keir Starmer, would do the same thing, they said.

It’s an argument that may have at least some truth. Privately, Labour officials accept they would take similar macroeconomic decisions if in power now.

That’s no consolation for Sunak amid widespread public dissatisfaction with the Tories after 13 years in power.

With political and economic numbers heading in the wrong direction, Sunak faces major decisions over the summer that may determine whether he can raise his party’s fortunes in the second half of the year.

One is whether and how to refresh his top team. Some in Downing Street have argued for cabinet changes ahead of the summer recess. But a person familiar with the matter said it’s most likely to come in the first half of September. That’s because the party first has to deal with three special elections at the end of July.

This week, the possible collapse of Thames Water reopened awkward conversations about the Conservative record on privatization and the toxic issue of sewage being pumped into rivers by water companies.

It led multiple ministers to privately speculate that Environment Secretary Therese Coffey — a Truss confidante — could be in the firing line come the reshuffle. An ally of Coffey insisted she inherited a department with huge problems, and had delivered important work in the last six months.

Home Secretary Suella Braverman’s competence was was also in focus after the Court of Appeal ruled against her department’s controversial plan to deport asylum seekers to Rwanda. Sunak is expected to keep her in post, a person familiar with the matter said.

However, Tory right-wingers suggested she could resign if the government’s appeal to the Supreme Court fails and Sunak then declines to commit to taking the UK out of the European Convention on Human Rights, which has been a barrier to the Rwanda policy.

Speculation about the futures of Coffey and Braverman is symptomatic of a wider government malaise, with ministers offering anonymous criticisms of their colleagues’ performance.

Some sniped about Business Secretary Kemi Badenoch for toning down the so-called bonfire of European Union laws post-Brexit. An ally dismissed her critics as a fringe group of hard-line Brexiteers.

And despite the announcement of a long-term workforce plan for the National Health Service on Friday, some ministers are underwhelmed by Health Secretary Steve Barclay, with Britons still facing record waiting times for treatment.

With Downing Street wanting to promote younger women, candidates touted for promotion include Children’s Minister Claire Coutinho and Pensions Minister Laura Trott.

Changes Sunak makes in his cabinet will define another live question: the Tory electoral strategy.

The party’s right — and some in government — want him to campaign to leave the ECHR, arguing a return to Brexit-style arguments would clearly differentiate them from Labour and allow them to accuse Starmer of being soft on immigration.

Why UK Tories Resent Europe’s Human Rights Court: QuickTake

Other Tories are squeamish, seeing threats to leave the ECHR as impractical and potentially destroying Sunak’s hard-won credibility with other international leaders.

Those MPs say Sunak’s best hope is pivoting away from policies aimed at satisfying the right, instead using a more moderate platform to target middle class voters in the south of England who are considering voting Liberal Democrat.

But the real decider of the election manifesto’s content will be the economy, a government official said. That means that for now, it remains uncertain.

--With assistance from Joe Mayes and Leonora Campbell.

Author: Alex Wickham, Kitty Donaldson, Emily Ashton and Ellen Milligan