A cash crunch is persisting in India, pushing short-term borrowing costs above a key policy interest rate and posing risks to an economy that needs cheaper funding to sustain its recovery.

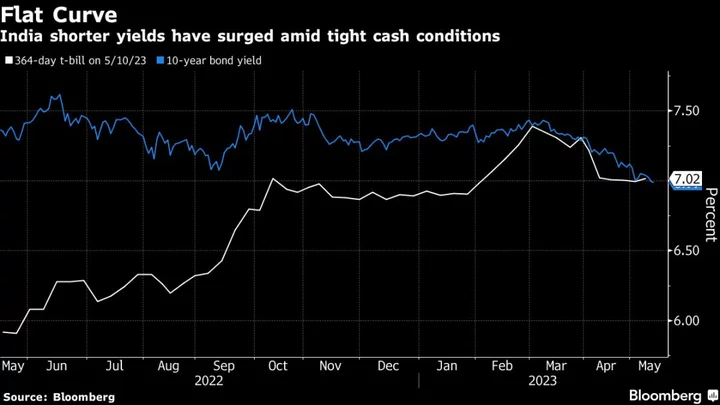

After a surge in recent weeks, the weighted average call rate which Reserve Bank of India closely monitors, has shot above its policy rate ceiling of 6.75%. Yields on one-year treasury bills also have exceeded those on 10-year government debt, an anomaly often associated with a malfunctioning bond market.

The funding squeeze indicates a clogged-up financial system that is starting to hurt appetite for bonds and further raising financing costs just as the RBI has paused monetary tightening amid easing price pressures. But economists say the situation may linger for a while, with the central bank still determined to fight inflation and expected to offer short-term liquidity relief only.

“With the rate-hiking cycle behind us, liquidity management will now be the key focus of monetary policy,” said Gaura Sen Gupta, economist at IDFC First Bank Ltd. “As long as the stance of monetary policy remains as withdrawal of accommodation, liquidity conditions are likely to remain tight.”

A gauge measuring excess cash that lenders park with the RBI has dropped to 484 billion rupees ($5.9 billion) from a high of 9 trillion rupees in 2022, as the central bank delivered a series of rate hikes and drained liquidity to tackle inflation.

While the latest funding squeeze mainly resulted from the RBI’s policy tightening, a buildup in the government’s cash surplus and uneven liquidity distribution among banks have made matters worse, said Gaurav Kapur, chief economist at IndusInd Bank Ltd.

The bond market is already feeling the pinch, with yields on six-month commercial paper of non-banking finance companies having risen 10 basis points this month. A Friday auction of sovereign bonds saw muted demand, with a bid-to-cover ratio of 2.6 times, according to ICICI Bank.

The spike in the overnight rate reflects asymmetrical distribution of funds between bigger and smaller banks, which fuels volatility in the money market and contributes to less efficient credit allocation, according to Soumya Kanti Ghosh, chief economic advisor at State Bank of India.

If the cash squeeze keeps worsening, it may pose risks to an economy that has delivered stellar growth since the pandemic but now faces headwinds from slowing global demand to a heat wave that threatens the nation’s thriving farm sector.

“High rates reflect tightening liquidity and clouded financing conditions for firms with weaker credit profile,” said Soumyajit Niyogi, director at India Ratings and Research Pvt. “Such firms may find it difficult to survive sustained tight financing conditions, leading to clustered credit events. Inter-linkages may also trigger contagion, potentially impacting the larger economy.”

But for now, economists say the RBI will likely refrain from using potent liquidity injection tools to push rates down sharply, as it may want to keep borrowing costs relatively elevated to rein in inflation and provide a buffer for the local currency.

The central bank is expected to initially rely on longer-dated variable bond repurchase agreements and foreign exchange intervention to ease the funding squeeze, said IDFC’s Sen Gupta, adding that an expected large dividend payout by the RBI to the government will also help offer more liquidity.

“As far as injection of permanent liquidity is concerned, we think RBI will not attempt to do so as long as policy stance doesn’t move to neutral,” ICICI Securities Primary Dealership economists including A. Prasanna wrote in a note, referring to options including RBI’s open-market bond purchases and lowering banks’ reserve requirements.