Moscow is trying to destabilize Moldova, but the tiny former Soviet republic can join the European Union by 2030 alongside its breakaway Transnistria region despite the current presence of Russian troops, its president said.

The secret to solving Moldova’s separatist conflict will be to pursue economic reforms and fight corruption. That will put the nation of 2.6 million — one of Europe’s poorest — on a clear EU accession path and show people in Transnistria that ties with the bloc, rather than Russia, will benefit their lives, President Maia Sandu said.

“The sooner we increase living standards, the sooner we will have the chance for the reunification,” Sandu, 51, said in an interview in Chisinau on Tuesday, two days before she hosts a security summit of European leaders. “100%, that’s our objective.”

The EU’s foreign affairs chief Josep Borrell said there are precedents for countries grappling with conflicts to join — and that he sees Moldova becoming an EU member.

“Look at Cyprus,” Borrell told reporters in Chisinau on Wednesday, referring to the EU member whose north is Turkish-controlled. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, also in the Moldovan capital, praised the government for “good progress” on reforms, which may pave the way for accession talks.

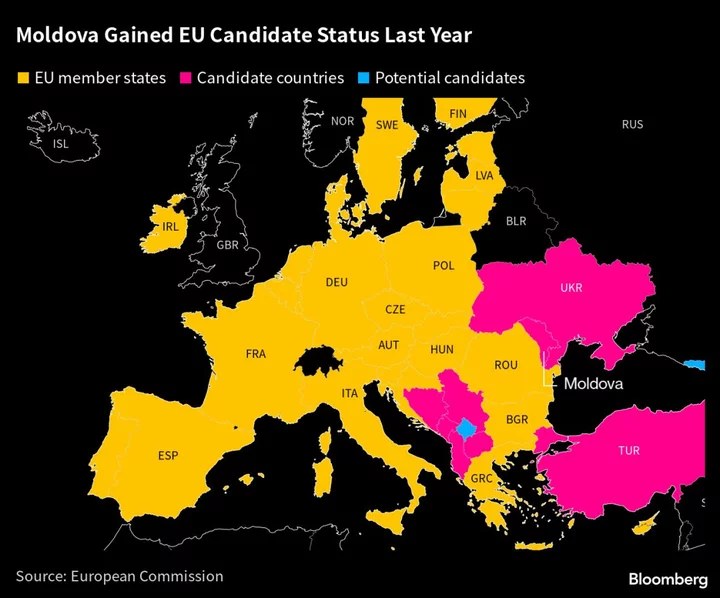

Like Ukraine, where protests ousted Moscow-backed leader Viktor Yanukovych in 2014 when he reneged on a deal allowing closer cooperation with the EU, Moldova won candidate status from the bloc last year.

It has since leaned on western support to weather financial turbulence, a wave of refugees from the war in neighboring Ukraine, war-caused power shortages and double digit inflation. The cost-of-living crisis has hampered efforts to increase people’s living standards and focus on reforms required to join the EU, especially on the judicial front, Sandu said.

At the same time, the government in Chisinau accuses Russia of seeking to quash Moldova’s EU membership aspirations by fomenting instability, backing pro-Kremlin political forces and organizing protests against reforms aimed at increasing transparency and the rule of law.

Moscow has repeatedly denied interfering in Moldova’s affairs but maintains more than 1,000 troops in Transnistria that western military analysts say pose a risk both to stability in Moldova and security in Ukraine to the east. In February, Sandu cited intelligence received from Ukraine saying Russia was trying to overthrow her government.

“Unfortunately Russia will continue to be a source of instability for many years to come,” Sandu said. “We have felt Russia’s attempts to destabilize our country and to undermine our efforts to build strong institutions and strong democratic processes, and that’s why EU integration is so important to us,” she said.

The government’s pre-accession reforms, which include anti-corruption efforts and crackdowns on oligarchs accused of draining public finances, have also faced opposition from pro-Russian political parties, which have called for Sandu’s resignation.

As Moldova prepares for presidential elections in 2024 and general elections a year later, Sandu said her party is working hard to maintain pro-European sentiment and avoid a backsliding in support for exiting Moscow’s orbit.

There’s also the need to peacefully solve the standoff with Transnistria, which fought a war with Moldova in 1992 after declaring independence in 1990. While the sliver of territory home to fewer than 500,000 people hasn’t been recognized by any United Nations member, a frozen conflict could torpedo any chance of joining the EU.

Another factor is security. While Moldova’s neutrality is enshrined in its constitution, the destruction brought by Russia’s war in Ukraine has prompted a public discussion over whether to explore joining NATO.

That sentiment has only been bolstered by comments from Moscow. In February, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov called Moldova “the next Ukraine,” in reference to his country’s opposition to former eastern bloc nations joining western alliances such as the EU and NATO.

“Of course we don’t feel safe,” Sandu said. “Today the majority of people still believe that neutrality should be kept. What will happen in six months or in a year from now, we’ll have to see.”

--With assistance from Karolina Sekula.

(Updates with comments from Borrell, von der Leyen from fourth paragraph. An earlier version was corrected to remove reference to Sandu seeking reelection.)