Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni could be forgiven for feeling any schadenfreude this week while looking on at Germany’s unfolding budget debacle.

A string of fiscal wins for Rome has just coincided with a crisis rocking Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s coalition in Berlin after a calamitous court judgment cast doubt on the financing plans for Europe’s biggest economy.

Italians weary of German lectures on budget prudence can sense the irony, even though diplomacy is likely to prevail when Meloni pays a visit to her counterpart on Wednesday.

“I admit it — I couldn’t help feeling vindicated,” said Carlo Alberto Carnevale Maffe, a professor of business at Milan’s Bocconi University. “Germans make mistakes too.”

Italy, long associated with political chaos, is enjoying relative stability as Meloni keeps her fractious coalition in line. Despite delivering on expensive promises to voters, the government is no longer on the brink of a junk rating, and ministers just cashed in by selling a stake in the country’s oldest bank.

The contrast with Germany is striking as Scholz’s alliance reels from an unprecedented crisis. An emergency spending freeze is in effect after a ruling by the top court in Karlsruhe cast doubt on Berlin’s public-finance strategy of spending by using special funds that aren’t part of the federal budget.

While the fates of Europe’s economies are intertwined, Germany had already been having a torrid time after the shock therapy of weaning itself off Russian gas combined with a Chinese-led drop in global demand to stall growth. The Bundesbank reckons a recession is probably under way.

Germany’s doldrums evoke a prior era when it earned a reputation as the “sick man” of the region. EU forecasts last week confirmed one aspect of that may turn out to be true: this year is likely to be the first since 2003 when Italy’s economy grew and Germany’s didn’t.

One enduring irony of Berlin’s budget predicament could be a prolonged hit to growth just as Italy benefits from a whole raft of investment thanks to EU recovery funds that will help drive expansion next year.

Germany is likely to face a clampdown on spending, says Erik Nielsen, chief economic adviser at Unicredit, who describes the court decision as a “disaster” that will force tough government choices to curb deficits.

“They’re not going to go out and cut pensions, right, or they can’t fire people in the public sector overnight,” he told Bloomberg Television. “They are going to cut stuff they can cut, and that’s investment. That has a long-term negative impact.”

The juxtaposition of both countries this week underscores their uneasy relationship in past decades. German officials balked at the prospect of Italy joining the euro in the 1990s, worried that its weaker public finances and tolerance of inflation would undermine the fledgling currency.

Fast forward to 2023, and the danger that a newly elected populist government in Rome would dare to stretch the country’s fiscal position kept Italy under investor scrutiny, not least as the economy underperformed forecasts.

Meloni unveiled a loosened budget in September to meet campaign pledges, and the spread between the bond yields of Italy and Germany — a key measure of risk in the region — widened to 210 points for the first time since January.

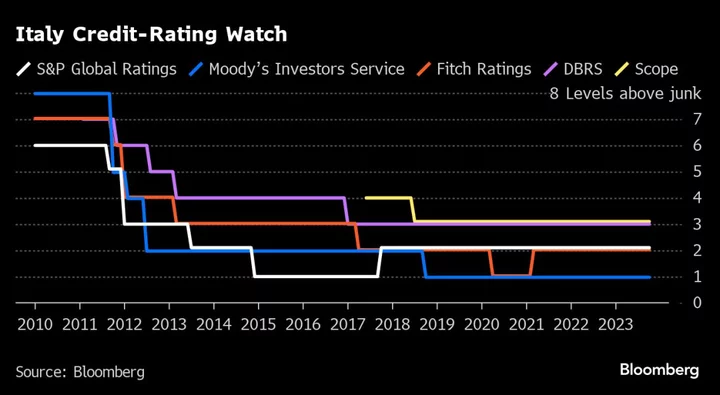

In the past month however, successive ratings companies maintained stable assessments on the country. Most significantly, Moody’s Investors Service, which had put Italy at the brink of junk just before Meloni’s election, raised its outlook to stable last week.

With the spread even touching below 170 points at one point on Tuesday, the government pulled off the sale of a $1 billion stake in Banca Monte Paschi di Siena SpA that had been in the works for years.

For all Meloni’s recent triumphs, Italy remains an economy in urgent need of repair. Its debt, at about 140% of gross domestic product, is second in the euro area only to Greece, and its deficit remains well above the EU’s 3% limit.

It’s German fiscal strength — the country’s debt burden is less than half as big as Italy’s — that underpins confidence in the region’s ability to weather shocks.

On Tuesday, Italy was classed along with Germany as not fully complying with EU fiscal rules by the European Commission, which put France in an even naughtier category of being at risk of flouting its guidance altogether.

Italian officials may have again savored the moment of not being the worst performer, but Brussels still reckons their underlying situation is challenging.

“If we look at state finances, we still have a ways to go,” said Carnevale Maffe at Bocconi. “We should remember our own faults too. We’re not out of the woods.”

--With assistance from Francine Lacqua, Christoph Rauwald and Chiara Albanese.