For an Italian government prioritizing fiscal prudence, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s coalition is sailing close to the wind.

The Brothers of Italy leader’s right-wing alliance with the League and Forza Italia is increasingly at loggerheads over which spending pledges the indebted country can still afford to deliver amid mounting investor scrutiny.

The combination of restless coalition partners and less money available because of a poor economic performance augurs weeks of public bickering and testy negotiations as Economy Minister Giancarlo Giorgetti prepares a 2024 budget. Adding to the pressure, European Union deficit limits are due to apply again in January.

While political squabbling is par for the course in Italy, it’s playing out in front of fickle markets focusing on the long-term sustainability of its finances, and nervous EU partners debating how stringently to reapply their rule curbing deficits at 3% of output.

Meloni’s coalition is supported by Matteo Salvini’s League and Forza Italia, the party founded by Silvio Berlusconi which is now headed by Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani. While both parties share right-wing values, they have been clashing on how far the state should be involved in companies and how to proceed with the sale of state-owned stakes as a way to finance the budget.

Meloni said Thursday she hopes the EU will be able to agree on new budget rules before the old ones kick in again next year. Leaders in the euro zone remain at odds on how strict the limits on debt and deficit should be. Germany and other countries are pushing for stricter fiscal discipline, while Italy backs more flexibility.

“Going back to pre-Covid limits would cause an economic contraction for the European economies, and for ours. It would be dramatic,” she said during a late-night press conference.

There’s no sense yet that the stability of Meloni’s government is under threat, but the emerging argument is likely to present the biggest test yet both of the coalition’s resolve to stay together, the patience of Italy’s peers, and the forbearance of investors.

“The ultimate judge is not Brussels, but the trading room,” said Carlo Alberto Carnevale Maffe, professor of business strategy at Milan’s Bocconi University. “Giorgetti and Meloni know this because they’re signaling to the coalition that resources are limited. They know they can’t play games with markets.”

The yield on Italy’s 10-year debt was 5 basis points lower at 4.35% on Thursday, but still remained set for the biggest weekly gain in two months, hovering close to the highest since March.

That left its premium over German peers — long considered a major gauge of risk in the region — at 174 basis points, near the highest since early July.

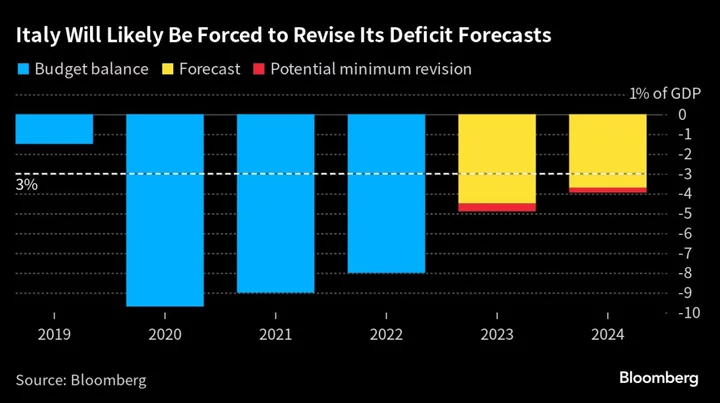

The backdrop is the drastic worsening in Italy’s budget deficit confronting Meloni and her colleagues. While the 2024 outcome is projected to show marked improvement from this year, it’s still looking likely to be closer to 4% than the 3.7% originally envisaged.

That puts it further away from the 3% limit that will kick in in January as the EU-agreed suspension on that regime for the period of the pandemic comes to an end. Countries are currently negotiating the fine details on interpreting those rules.

Italy’s weak growth isn’t helping its public finances. Expansion in the euro region’s third-biggest economy was 0.6% in the first three months of this year, but it then shrank 0.4% in the period from April to June.

Growth may then sputter as the country struggles with rising interest rates and weakening global demand. The government is still hoping to achieve overall expansion of 1% this year.

Coalition partners want to stick to some of the spending promises they made to get elected. Meloni has promised a cut in the tax wedge, which is the difference between what workers cost employers and what gets paid out to them.

Her pledges also include measures to incentivize parenthood — including new preschools and longer paid leave — and preserving generous pension benefits.

The League’s Salvini wants to take ownership of any tax cuts and to build a bridge to Sicily from the mainland. He’s less preoccupied about borrowing, while Tajani of Forza Italia is preaching prudence.

Meloni is trying to reconcile all those positions while also avoiding a market confrontation.

The Italian prime minister is only too aware of the dangers, having served in Berlusconi’s government that collapsed under investor pressure in 2011. She took office last year just as former UK premier Liz Truss confronted financial turmoil too.

For now, Meloni is trying to square the circle by raising cash. The government’s attempt in August to implement a 40% levy on banks’ extra profits encountered market pushback and led to a watering down of the measure.

Meanwhile Giorgetti is considering selling state-owned companies, and moving forward on the planned sale of lender Monte dei Paschi di Siena.

Meloni attempted to patch up differences with colleagues at a meeting in Rome on Wednesday that Giorgetti didn’t attend. There’s no sign yet of a clear consensus on the way forward.

“At some point, Salvini and other party leaders will be given some kind of ultimatum,” said Martina Carone, a political analyst at YouTrend, a polling and research company.

Ministers have until the end of the month to agree on a budget. Clouding the fiscal picture is need to conform with accounting requirements to accommodate the so-called “superbonus” tax break for climate-friendly renovations that will now massively swell the deficit for this year.

The smokescreen that provides could yet offer some fiscal wiggle room, but Italy’s EU partners — who have also bankrolled an investment binge in the country borne out of pandemic-era solidarity — are likely to be watching closely.

Ultimately, Carone expects the premier to succeed in papering over any cracks in the alliance for now, because disagreements are mainly surfacing ahead of European Parliament elections next June.

“I don’t think Giorgia Meloni will allow any real differences to emerge neither within the coalition nor with Europe,” she said.

--With assistance from James Hirai.

(Updates with coalition divisions in fifth paragraph)