As the lira was approaching a decade of continuous losses, Turkish policymakers hit on an idea that promised a quick fix, and it helped stave off another currency crisis.

But nearly two years on, a government-backed savings program that bought the Turkish currency months of stability has become too big to unwind and too dangerous to live without.

Initially seen as an emergency measure, it’s since become an indispensable but costly tool, with the central bank unveiling one of the biggest steps yet to scale it back in an announcement in the early hours on Sunday.

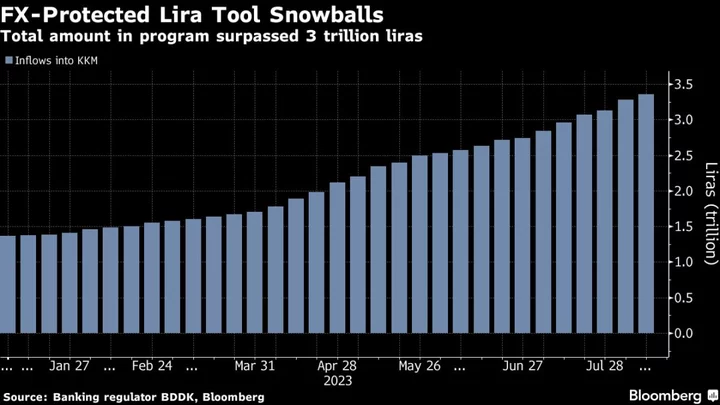

At $124 billion, foreign exchange-linked savings — protected from depreciation against hard currencies — now account for more than a quarter of total deposits, dwarfing the central bank’s gross reserves. The program, known by its Turkish acronym KKM, is increasingly a drain on state coffers and a constraint on policymakers devising a more conventional path forward for the $900 billion economy following elections in May.

As the central bank led by Governor Hafize Gaye Erkan prepares to forge ahead with another interest-rate hike this week — a decision that would have been all but taboo under her predecessor — KKM might turn out to be one of the lasting legacies of an era of unorthodox economics under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

“We don’t anticipate the central bank will be in a position to reverse this deposit scheme facility in the medium term, given the poor FX reserve coverage and the profile of upcoming FX-debt redemptions in the Turkish economy,” Citigroup Inc. analysts including Luis Costa said in a report last week.

Despite the massive shift by Turkish savers — KKM has seen no weekly outflows since January — S&P Global Ratings considers the Turkish economy to be “more dollarized” now than it was in 2019 following a currency crisis.

Under the mechanism, lira depositors can hedge against currency losses by getting state-guaranteed compensation for any depreciation that exceeds the interest on the accounts. Since inflows can come by converting hard-currency accounts, they became an additional source of dollars for the central bank’s sagging reserves.

With its latest decision, the central bank is signaling lenders should discourage clients from renewing their KKM deposits, forcing those banks that don’t meet certain targets for conversions into regular lira accounts to buy additional government bonds.

Lira deposit rates, which had been falling before the weekend decision, are now expected to increase, an official with direct knowledge of the plans said, asking not to be identified because of the sensitivity of the matter.

KKM Rollback

“The first aim of the regulations seems to be to reduce the share of KKM accounts,” said Istanbul-based economist Haluk Burumcekci. “The new measures will have a substantial impact on deposit rates, indicating the central bank’s policy rate increases will continue missing market expectations.”

The tool remains a critical currency backstop at a time when Turkish rates remain deeply negative when adjusted for inflation. Turkish savers have continued to flock to KKM in the absence of other appealing options apart from gold and stocks.

Turkey’s options are limited because any abrupt wind-down would likely push people to load up on dollars, threatening official reserves that are too depleted to meet a burst of demand for hard currency.

But the economic side-effects have been disruptive enough that the central bank is having to react. State lenders have had to sell billions of dollars on the market to help meet demand for hard currency driven by maturing KKM accounts.

Payments to compensate KKM holders have meanwhile added to a liquidity glut in the financial system that the central bank had to drain by raising the amount of money lenders have to set aside to cover FX-protected deposits.

Lira Liquidity

“Although bank funding by the Turkish central bank has declined since the elections, lira liquidity in the system continued to increase, driven, especially recently, by higher lira deposits likely resulting from payments for the FX-protected deposits,” Goldman Sachs Group Inc. economists Clemens Grafe and Basak Edizgil said in a report.

The Turkish Treasury has until now shared the program’s costs with the central bank, which hasn’t yet disclosed its contribution. The Treasury paid out 93 billion liras ($3.4 billion) last year.

The mechanism “causes immense losses to the central bank,” according to Burumcekci.

After the May ballots won by Erdogan and his allies, Turkey’s ruling party introduced a bill that passes the costs entirely to the central bank. Officials have argued such a transfer would make the budget more transparent and solidify public finances.

Even as KKM casts a shadow over policymaking, officials have been reluctant to discuss its future.

When asked last month about what could be next, the central bank governor only said the focus now is on diversifying lira saving tools.

Vice President Cevdet Yilmaz, another key member of a new team installed by Erdogan to steer the economy, has said the government could revisit the issue once it bulks up reserves and concerns subside over the exchange rate.

A Bloomberg report that Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek expressed strong criticism of the program during a private meeting with foreign investors prompted a denial from his ministry.

The next pressure point is likely to come once the legislature reconvenes this fall and likely passes a law shifting the full burden of KKM on to the central bank.

Since the monetary authority — unlike the Treasury — collects no revenue, it would have to make payments by printing new money. That will cause “the monetization of costs stemming from the exchange rate,” according to Coskun Cangoz, who heads the Fiscal and Monetary Policy Research Center at the Ankara-based think tank TEPAV.

The result, in all likelihood, would exert upward pressure on inflation, he said, and could put the lira at risk if looser monetary conditions drive people to abandon the FX-protected deposits.

“It won’t be surprising for an exit from the KKM to take longer than expected under these conditions,” Cangoz said.

--With assistance from Asli Kandemir, Ugur Yilmaz and Firat Kozok.