Japanese food maker Yaokin Corp. shocked generations raised on its Umaibo puffy corn snack last year when it increased its price from 10 yen ($0.07) for the first time in 42 years. Facing an outcry over a 2 yen increase, the company took out advertisements to apologize.

Now it’s a different story: hardly anyone batted an eye when a raft of companies raised prices on thousands of consumer staples, from instant noodles to bottles of soy sauce, at the start of June.

The growing acceptance of inflation is one of several factors, along with signs of better corporate governance and Warren Buffett’s endorsement, which have pushed Tokyo’s stock market to 33-year highs, investors say. Now, many are beginning to see inflation, including its expected boost to corporate margins and consumption, as the most concrete reason to believe the world’s third-biggest economy is finally emerging from decades of little to no growth.

“We have been waiting for this inflection point for so long, and we’ve had a few false starts,” said David Chao, global market strategist for Asia Pacific at Invesco Asset Management. “I think this time around the inflation and growth dynamics are different and more sustainable.”

Japan’s consumer price index rose 4.3% in January from a year earlier, the fastest gain in 41 years. While the surge was initially driven by a global energy crisis rather than stronger underlying demand, the price pressure is proving sticky enough that economists expect the trend to continue even as import costs decline.

The Bank of Japan’s continued stimulus to bolster inflation while other global central banks do the exact opposite is also seen helping Tokyo stocks. Most economists see the BOJ maintaining its ultra-easy policy when it meets this week, but 55% of them now also believe the central bank’s stable 2% inflation target will be achieved, compared with 40% two months ago. While some fear market turmoil once the BOJ recognizes a faster rate of inflation and hints at an exit from ultra-loose monetary policy, many investors say the benefits of sustained price growth outweigh the downsides of a policy shift, especially with the central bank likely to move cautiously.

“We may see a rate increase and while that has positive and negative effects, I think the net effect will be a signal to the market that Japan is both continuing to recover from the pandemic and has ‘normalized’ its economy,” said Angus McKinnon, portfolio manager at The L.T. Funds.

Read more: BOJ’s Ueda Likely to Hold With Bond Market on His Side For Now

Investors are hoping that under inflation, companies will be able to raise prices without encountering too much pushback from customers. Corporate results announced last month showed some positive signs. Major steelmaker Nippon Steel Corp. reported record sales and profit after passing on higher materials costs to clients. Chinese restaurant chain Ohsho, known for its gyoza dumplings and other cheap and filling dishes, also reported strong results despite a series of price hikes.

It’s not just about corporate margins; it’s also about a possible sea change in consumer behavior as people are no longer able to snag better deals just by waiting.

“Deflation encourages people to postpone spending and companies to hold off investing. Modest inflation – and at 4% Japan’s inflation is relatively modest – turns the momentum the other way,” said Alex Stanić, head of global equities at Artemis Investment Management.

Putting Cash to Work

While many believe the stock market is due for a slowdown after rising nearly 25% in the year to date, some investors are also hoping inflation will provide an additional boost in the long run. The thinking is that the country’s notorious savers, hoping to maintain the value of their assets, will shift more of their savings into domestic stocks. Households keep around half of their net worth in cash and deposits.

“This leaves ample fire power to fuel equities investments,” said Hilde Jenssen, head of fundamental equities at Nordea Asset Management.

Hayato Yamagami is an example. The 26-year-old office worker said he recently realized the impact of inflation on his purchasing power when he saw the menu at a McDonald’s, where a 100-yen coin was no longer enough to buy a basic hamburger or small French fries.

He’s begun investing around 30,000 yen every month in stocks and mutual funds, taking advantage of Nippon Individual Saving Accounts (NISA), a tax-exemption program aimed at encouraging households to invest in riskier assets. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has decided to expand tax breaks for it next year.

“You can’t increase your money by putting it in a bank,” Yamagami said.

While recent exchange market data shows retail investors have been selling into the rally, the longer-term trend offers a more bullish signal. Individuals were net buyers of Japanese stocks in 2021 and 2022, the first time they were net buyers for two years in a row this century. Some analysts see that as a sign the market’s bottomed out, since the only other times they were net buyers this century were in 2008 and 2011, preceding market gains.

Investors expect inflation to encourage more businesses, too, to put their cash to work. As Japan entered decades of deflation and slow growth in the 1990s, Japanese companies focused on paying off their debts, and subsequently, hoarding cash. Japan Inc.’s cash pile snowballed to over 320 trillion yen last year from 168 trillion yen in 2008, according to BOJ data.

In addition to promising record-high dividend payments, companies are conducting more share buybacks, motivated by a government push to bolster shareholder returns and a stock exchange campaign calling for higher price-to-book ratios.

Businesses are also boosting spending on new technologies and infrastructure. Osaka-based Panasonic Holdings Corp., which supplies EV batteries to Tesla Inc., as well as producing consumer electronics, plans to double its capital investments in the current fiscal year to a record 700 billion yen.

“Under deflation, the value of your products and inventory keeps falling while the value of your debt doesn’t decline. So you don’t have any incentive to expand your balance sheet through leverage. That’s the biggest problem with deflation,” said Takashi Kozu, president of the Securities Analysts Association of Japan and a former central banker. “During the past thirty years, Japanese companies stopped taking risks... As a result, we missed opportunities to renew industries,” he said.

False Starts

Such concerns about the diminished position of Japanese businesses mean some are skeptical that the recovery will continue. Global investors are still underweight on Japan, although Morgan Stanley equity strategist Daniel Blake said those positions had shrunk over the last 18 months.

There have been a few false starts since the asset-inflated bubble economy burst in the early 1990s, leaving companies saddled with non-performing loans and consumer confidence shaken. A modest, export-led recovery was cut short in 2008 by the global financial crisis. The market’s initial excitement over Abenomics, reflationary measures undertaken by late Prime Minister Shinzo Abe from 2013, petered out quickly.

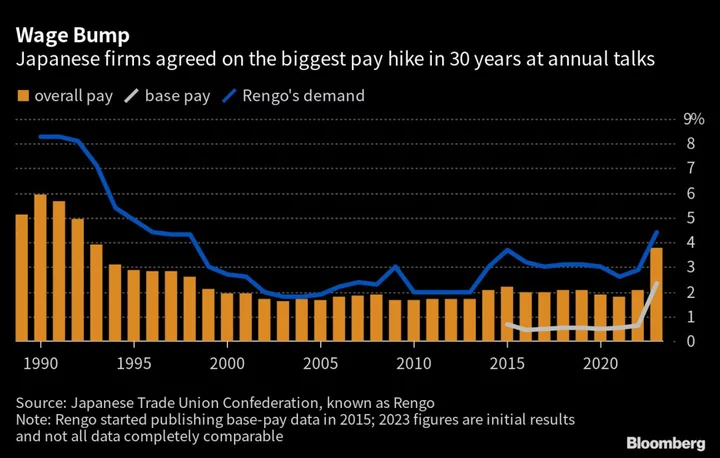

A key difference this time is that the momentum is accompanied by an increase in wages. Many Japanese workers, who had seen little or no growth in pay for decades, are promised bigger paychecks following recent labor negotiations. Uniqlo-operator Fast Retailing Co. in January announced raises of up to 40% for full-time employees. Nintendo Co. and Toyota Motor Corp. followed suit as Kishida publicly put pressure on corporations to boost salaries as part of his “New Capitalism” push for broader income distribution.

While recent monthly data show inflation is still outpacing pay gains, the overall trend is still positive, analysts said.

“We actually live in a nominal world – wages, rents, stock prices, prices in the shops – all this is nominal. Domestically generated inflation, driven by labor shortages, will feel good,” said Peter Tasker, a financial strategist and co-founding partner of Arcus Research Limited. “Japan is finally and decisively moving out of deflation.”

--With assistance from Yasutaka Tamura and Aya Wagatsuma.

Author: Hideyuki Sano, Winnie Hsu and Ishika Mookerjee