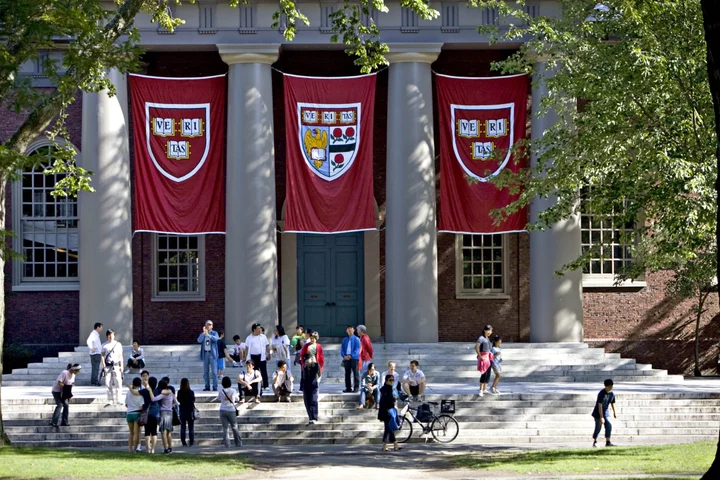

Harvard University was accused by minority groups of violating federal law by giving preferential treatment in the admissions process to children of alumni and wealthy donors, days after the US Supreme Court struck down the use of race-based affirmative action policies.

The long-standing practice flouts a provision of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that bars racial discrimination in programs that receive federal funds, because about 70% of legacy admissions are White, the groups said in a complaint filed Monday with the US Department of Education.

“Each year, Harvard College grants special preference in its admissions process to hundreds of mostly White students — not because of anything they have accomplished, but rather solely because of who their relatives are,” they said in the complaint.

The minority groups seek a probe into Harvard’s use of donor and legacy preferences as well as a declaration that the school will lose federal funds if it doesn’t end the practice. The groups also want Harvard to ensure that applicants with family ties “have no way to identify” themselves in the admissions process.

The complaint comes as the US continues to grapple with the fallout of the Supreme Court’s ruling ending affirmative action, which has been used by universities to diversify campuses after decades of racially discriminatory admissions practices. Harvard forcefully defended affirmative action and said it would find other ways to ensure diversity.

Harvard declined to comment on the complaint.

Read More: Harvard Defends Diversity After Defeat in Supreme Court

Justice Neil Gorsuch, in hearing arguments in October, suggested eliminating the legacy preferences given to the children of alumni and others who gain an edge such as athletes and big-money donors. But colleges are so far mostly loath to scrap such preferences, which keep donors happy.

While Massachusetts Institute of Technology has had a longstanding policy against legacy admissions, only a handful of other selective colleges have adopted such practices, including Amherst College and Johns Hopkins University.

The complaint was filed by the Chica Project, the African Community Economic Development of New England and the Greater Boston Latino Network. The groups called the practice an “unfair and unearned benefit” based solely on “the family that the applicant is born into.”

“Your family’s last name and the size of your bank account are not a measure of merit, and should have no bearing on the college admissions process,” said Ivan Espinoza-Madrigal, executive director of Lawyers for Civil Rights, which represents the groups.

The Supreme Court ruling stemmed from a suit filed by Students for Fair Admissions, an anti-preferences organization run by former stockbroker Ed Blum. On Monday, Blum pointed to his organization’s statement after the Supreme Court ruling, which said the elimination of legacy practices “is long overdue.”

“Because Harvard only admits a certain number of students each year, a spot given to a legacy or donor-related applicant is a spot that becomes unavailable to an applicant who meets the admissions criteria based purely on his or her own merit,” the groups said in its filing.

The university receives “substantial federal funds” and is therefore bound by landmark civil rights law, which “forbid practices that have an unjustified disparate impact on the basis of race,” the groups said.

In anticipation of the Supreme Court ruling, a study by Georgetown University in March called for selective colleges to scrap their legacy policies. The report — “Race, Elite College Admissions, and the Court” — held that doing so would help elite universities “maintain their newfound (albeit still limited) levels of diversity.”

--With assistance from Janet Lorin.

(Updates with Harvard declining to comment)