Traders hunting for an edge in the $7.5 trillion a day foreign-exchange market are poring over a crucial gauge of economic resilience in the era of higher-for-longer interest rates: housing prices.

Strategists from JPMorgan Chase & Co. to Citigroup Inc. are digging into property and household-debt data to locate pain points among the world’s leading economies. What they’ve found is bad news for New Zealand and Sweden, where consumer strain may force policymakers to end their monetary tightening cycles without first reigning in inflation.

“Weak housing markets tend to impact currencies through their spillover on growth and their influence on central bank policy,” said Alan Ruskin, chief international strategist at Deutsche Bank AG. The key for traders is finding “where housing-sector vulnerability has kept growth softer, and policy more accommodative, than it would otherwise be.”

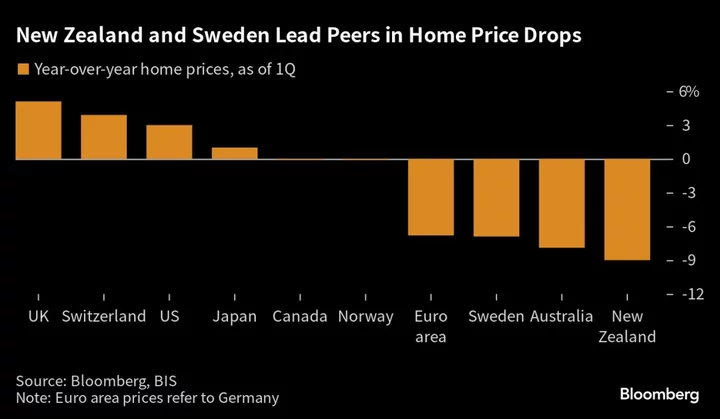

Sweden and New Zealand, it seems, stand out for the wrong reasons. Some of their key economic indicators are flashing warnings, with home prices sliding the most among developed nations and household debt exceeding 100% of disposable income in both countries.

Sweden’s jobless rate has soared over the past year and hovers around levels last seen during the peak of the pandemic. Annual consumer price gains are above 9% in the Scandinavian country, taking the real rate — or the key interest rate stripped of inflation — to negative 5.5%, the lowest among Group-of-10 peers.

New Zealanders, meanwhile, are increasingly falling behind on personal debt repayments, with policymakers warning in July that homeowners have yet to feel the full impact of a dozen straight rate hikes. The real policy rate is also below zero, with headline inflation triple the central bank’s 2% target.

Unemployment and high debt burdens would be less of a problem for commodity exporters, like Australia or Norway, that have seen the rising prices of iron ore and natural gas offer support to their economies. But in Sweden and New Zealand, they leave central bankers in a challenging position.

Their options at this point are to keep hiking rates to fight inflation, or adopt an easier monetary position that will jump-start economic growth. Currency strategists already see the odds of a premature end to monetary tightening as bad news for the krona and kiwi.

Relative-value trades are cropping up as a result, with Deutsche Bank, Citi and JPMorgan urging clients to short the krona against the currencies of stronger housing markets — such as Norway’s. Amundi Asset Management, meantime, expects New Zealand dollar to weaken versus its Australian neighbor.

Speculators have slashed their bullish bets on the kiwi by more than 50% since the end of February, with the currency itself down roughly 1% against the greenback over the same period. The krona, meanwhile, tumbled to all-time lows versus the euro in June and July.

“I’m more bearish on New Zealand than I am on Sweden,” said Paresh Upadhyaya, director of currency strategy at Amundi in Boston. “Household indebtedness has been a headwind and a focal point for central bank policymakers.”

Citigroup strategist Yasmin Younes echoed the opportunity in cross-currency trades, which offer positive carry and are less-vulnerable to moves in the US dollar or euro. The bets also benefit from strength in Norway and Australia, economies that typically see a boost from commodity exports.

“When mortgages start to have a big impact on housing activity or it puts a strain on household budgets, then those countries may be more vulnerable to an economic downturn sooner rather than later,” said Kathy Jones, chief fixed-income strategist at Charles Schwab & Co.