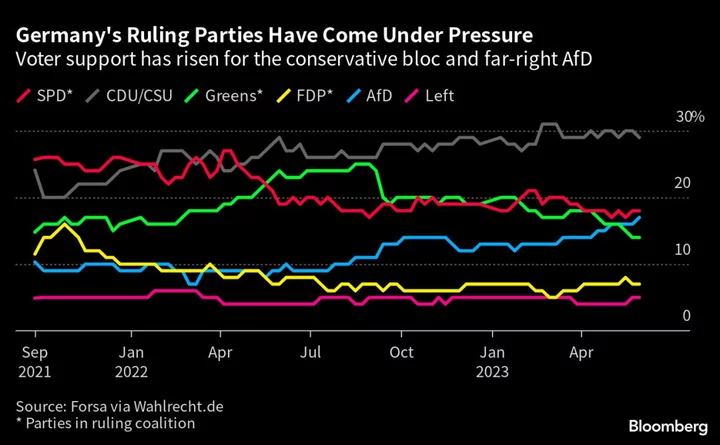

Germany’s far right has surged to new highs in opinion polls, tapping into citizens’ discontent over record-high migration, persistently painful inflation and costly climate protection measures to batter Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s government.

The Alternative for Germany, or AfD, which denies the impact humans have on global warming and wants to stop more foreigners from coming to Germany, is now tied with Scholz’s Social Democrats as the second-most popular party in the country, polling only behind an alliance of opposition conservatives.

Once viewed as a radical fringe group, the AfD is now attracting frustrated supporters of established parties. Its rise coincides with public resentment over high energy and food costs resulting from Russia’s brutal attack on Ukraine, and over escalating expenses linked to Europe’s efforts to reduce climate-damaging carbon emissions. By focusing on these issues, the populist party has successfully exploited cracks in Scholz’s ruling coalition, which includes the environmentalist Greens, the pro-business Free Democrats and the chancellor’s center-left Social Democrats.

“The coalition parties are losing support because they cannot convey a positive narrative for the future of the country,” Andrea Roemmele, vice president at the Berlin-based Hertie School, said in an interview. “When it comes to implementing their policies, there is constant disagreement and infighting between the FDP and the Greens — it’s this discord that is pulling down not only the Greens, but the ruling coalition as a whole.”

This internal dissent contrasts sharply with the new, unified stance struck by AfD leadership, said Roemmele, who noted that the far-right party has been able to attract more voters by tamping down their public battles. In addition, the AfD has capitalized on controversy surrounding an influx of more than one million war refugees from Ukraine and nearly 250,000 asylum seekers who came to Germany from countries such as Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq in the past year.

According to the latest Infratest Dimap poll, support for the AfD has jumped two percentage points to 18%, putting it on par with the Social Democrats. The conservative CDU/CSU bloc fell one point to 29%, while the Greens lost one point to 15%, the lowest recorded by this poll since September 2021. The Free Democrats remained unchanged at 7%.

Despite rising tensions, all other parties have ruled out working with the AfD, and Scholz’s three-party coalition is highly unlikely to break apart before the next federal election in 2025.

Nonetheless, the far-right resurgence is already limiting Scholz’s room to implement bold climate protection measures.

The main victim of the AfD’s rising popularity has been the Green Party, as its environmental agenda is being compromised by coalition partners seeking to distance themselves from unpopular measures.

With regional elections looming in the key states of Bavaria and Hesse in October, Scholz’s ruling coalition is already backtracking on climate-protection measures and watering down legislation such as a draft law forbidding homeowners from installing new gas boilers in a push to reduce carbon emissions in the housing sector.

A string of regional elections in the eastern states of Brandenburg, Saxony and Thuringia next year could bring landslide victories for the populist party, which is leading polls in the region. The former communist east is heavily dependent on lignite mining, and the government’s push to phase out coal by 2030 — eight years earlier than planned — is facing major push-back in these areas.

Asked to comment on the malaise of his Green party, Economy Minister Robert Habeck tried to play down the importance of polls and called on his coalition partners to focus on unity.

“I do not want to make polls the driving force behind my actions,” Habeck said in an interview at the sidelines of a conference in Berlin. “But an agenda that bets on division always benefits the dividing forces.”

Yet chances are low that this discord will end anytime soon.

Voter Backlash

“The main reason for the AfD’s good performance is a backlash against many measures and policies for which the ruling coalition stands and which many citizens do not want,” said Peter Matuschek, managing director at Forsa pollster. He cited the examples of phasing-out nuclear power plants, banning internal combustion engines in cars by 2035 and the proposed gas heating ban, all of which, he said, are opposed by a majority of German citizens.

“The AfD, as a clear protest party which is in fundamental opposition to the ruling coalition, is benefiting from this mood,” he said.

The political threat posed by the far right could also undermine already agreed-upon government efforts to cut carbon emissions by two-thirds by 2030, for example in the area of subsidies. Raising the diesel tax, introducing a kerosene levy or cutting commuter subsidies could reduce emissions but would meet with widespread resistance from working middle-class voters, who the AfD has been targeting.

The party’s rise is also a blow for the conservative opposition. During his campaign for the Christian Democratic party leadership in 2018, Friedrich Merz promised to halve public support for the AfD. Five years later, the right-wing populist party has almost doubled its percentage share in the polls.

In an interview with the Funke Mediengruppe, Christian Democratic Union Secretary General Mario Czaja attributed the AfD’s success to uncertainty over the governing coalition’s policies. “But of course we must also ask ourselves self-critically why these disenchanted people are turning to the extreme fringes,” he added.

Scholz is optimistic that his coalition can reach a compromise over the home heating law before the summer recess — even though, as the chancellor has said, the public is not currently in favor of stricter climate protection measures. An end to government infighting over the heating law could help restore support for the ruling parties.

Still, Scholz aides have pointed out that the government is obliged to fulfill its CO2 reduction goals simply because climate protection is now guaranteed in the constitution. Should his administration fail to reach its self-set targets, citizens could simply sue Scholz’s government in Germany’s highest court.

--With assistance from Petra Sorge and Arne Delfs.