UK economists are urging the Bank of England to halt sales of long-dated government bonds under so-called quantitative tightening after a collapse in bond prices threatened to lock in billions of pounds of losses for taxpayers.

Analysis by Lloyds Bank and Bloomberg showed that active sales of gilts held on the BOE’s balance sheet alone have cost the UK government £15 billion ($18.2 billion) in the past year, with the bulk of the losses on bonds dated 20 years or longer.

Sanjay Raja, senior economist at Deutsche Bank, said the BOE is crystallizing losses of about 55% of the value of each long-dated gilt it sells — far steeper discount it’s taking on short- and medium-dated bonds.

Raja and Sam Hill, head of market insights at Lloyds Bank Commercial Markets, said the BOE should switch sales to the short end to reduce losses. While the discount on long-dated bonds can be over 60%, it’s just 20% for shorter bonds.

“As long as the BOE continues to sell these long bonds, the bigger the hit to the public finances,” Raja said.

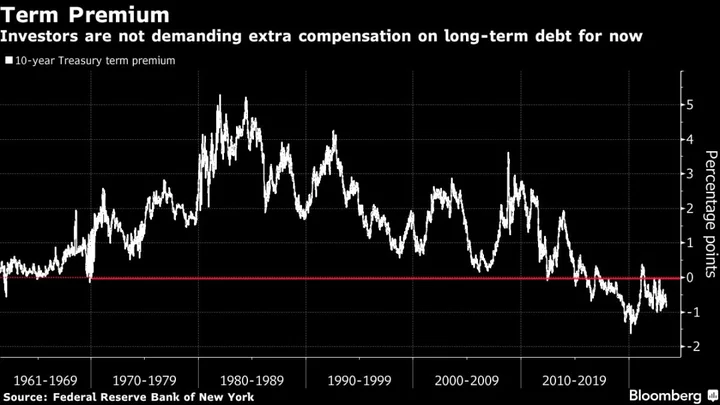

A spike in yields on 30-year gilts on Friday to the highest level since 1998 compounded the problem as the central bank attempts to shrink the asset portfolio it built up during more than a decade of stimulus. Rising yields means bond prices are falling, reducing the value of the assets the BOE is selling and forcing the Treasury to pick up the tab.

Under an indemnity signed in 2009, the Treasury must cover any losses on the QE program. That is complicating Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt’s job of stabilizing the public finances ahead of the election expected next year. Hunt has warned that the Treasury’s position is so tight he faces difficult decisions in his autumn statement on Nov. 22.

Quantitative easing generated £124 billion ($151 billion) of profits for the Treasury between 2009 and 2021. It was the main took the BOE used to stimulate the economy through the global financial crisis and pandemic. Raja expects even larger losses over the next five years.

The bulk of the losses are a result of higher interest rates, which the BOE pays on reserves it created under QE and cost more to service than the coupon income it earns on the bonds it holds. The BOE tightened policy to tame inflation, which was in double digits earlier this year.

The interest rate losses are unavoidable. However, losses caused by active sales are the result of deliberate BOE policy to unwind its QE portfolio. Raja said it has a duty to ensure taxpayers are not penalized by its gilt decisions.

Original documents from when QE was launched in 2009 instruct the BOE to “protect taxpayer interests.” A letter from then BOE Governor Mervyn King said: “The Bank will consider the appropriate mechanisms for selling assets, having due regard for the impact of those sales on the prices achieved.”

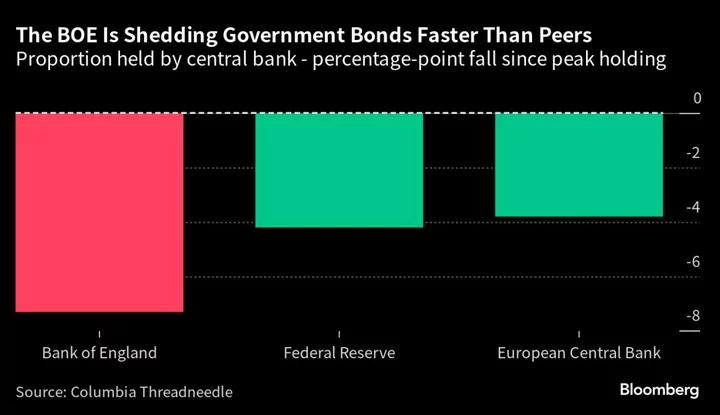

The BOE started actively selling gilts in November 2022 to accelerate its balance sheet reduction after assets mushroomed by £895 billion between 2009 and 2021 under QE. The initial plan was for £40 billion of active sales and to let £40 billion of gilts mature and run off over 12 months. Last month, the BOE stepped up the combined pace of reduction to £100 billion over the coming year.

The BOE raised the prospect of a change in the sale process in September. In a market notice it said it would “monitor whether the current approach of selling gilts evenly across short, medium and long maturity sectors in sales proceeds terms remains appropriate.”

It declined to comment on the economists’ proposals to reprofile the gilt sales.

Christopher Mahon, head of dynamic real return at asset manager Columbia Threadneedle, has compared the BOE’s plan to press on with cut-price gilt sales to an ill-timed decision by then-Prime Minister Gordon Brown to sell gold reserves at the bottom of the market in 1999.

Hill wrote in a note: “The UK’s QT arrangements have already left the government with less cash to spend on other things because the cash has instead been sent to the BOE to cover losses.”

He added that focusing active sales on short and medium duration gilts also worked for monetary policy reasons. Commercial banks need the right level of reserves for “policy to function efficiently.”

--With assistance from Andrew Atkinson.