The European Central Bank is about to test the resilience of the continent’s banking industry by making lenders repay about half a trillion euros in cheap pandemic-era loans — in one go.

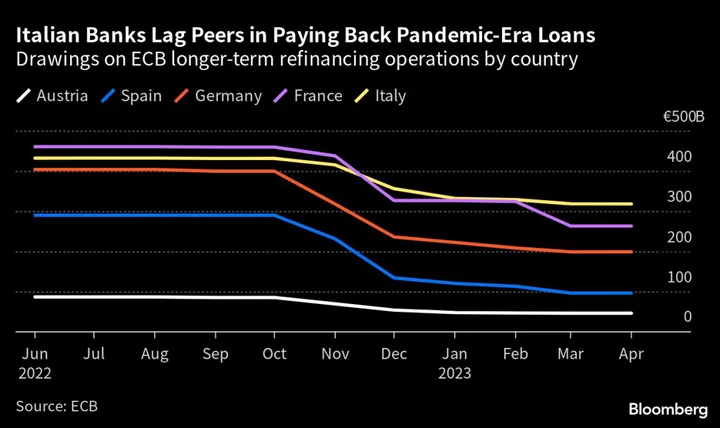

While the €4 trillion or so of excess liquidity sloshing around the financial system should limit the overall impact of the giant repayment, individual firms and countries could be strained, economists and analysts say. Smaller Italian lenders are the biggest concern, with Greek banks not far behind.

Italy’s outstanding borrowing under the ECB’s TLTRO program is more than the excess cash its lenders have parked at the ECB, meaning some of its banks will have to raise money elsewhere to repay the loans. Greek lenders’ excess reserves are more or less equal to what they owe the ECB.

As €476.8 billion of TLTRO loans come due on June 28, specific firms in Germany, France or other euro-zone nations could also feel the pinch, according to Reinhard Cluse, an economist at UBS Group AG. “In Italy or Greece, the aggregates are clear,” he says. “But even in other countries, there could be banks that borrowed in excess of their reserves at the ECB.”

The central bank is letting the TLTRO loans expire to help shrink its bloated balance sheet — and the facility’s job of letting banks navigate the Covid-19 storm is done. But the ECB’s own officials have concerns about the knock-on impact of higher borrowing costs on lenders with the most limited access to the money markets.

Andrea Enria, the ECB’s banking supervisor, said last month that some firms have a “material reliance” on TLTROs.

Italian banks may need to raise about €35 billion in 2023, and another €75 billion to prepare for more TLTRO loan repayments next year, according to estimates from NatWest Markets. “Some institutions, most likely the smaller banks, will be short cash even in the short term,” Joann Spadigam and other NatWest strategists wrote in a note to clients.

The good news is that lenders have plenty of options for alternative funding: one being the repo market, where firms lend to each other on a secured basis. Banks may also turn to the bond markets to plug any gaps or choose to pocket cash from maturing bonds they hold.

“Banks have relied on excess liquidity over the last couple of years, when compared with alternative means of funding such as the commercial paper market, covered bond market and long-term repo,” says Frank Gast, a managing director at Eurex Repo. “Now we’re seeing more long-term financing in repo over three-, six-, nine- and 12-month periods.”

For some, that’s evidence that smaller European lenders are putting contingencies in place for life after TLTRO.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“The repayment of the ECB’s largest TLTRO on June 28 has the potential to add to anxiety about the continent’s banking sector. If any banks were to be shunned in the money markets when they try to replace that official funding, the risk is that confidence in them could be sapped, prompting a flight from investors.”

—David Powell, senior euro-area economist. Read full note here.

Italian banks seeking cash in the repo markets — where collateral such as government securities can be pledged in return for liquidity — may find plenty of willing lenders, as liquidity remains so elevated. Nonetheless they’d still need to offer a sweetener to attract funding, according to UniCredit strategists, who see Italian repo rates rising toward 5 to 10 basis points above the ECB’s deposit rate, the market benchmark.

More Money?

Analysts doubt that the ECB would introduce a new facility to tide banks over, even if they did find themselves locked out of private funding markets. Most economists polled by Bloomberg this month said they didn’t expect the ECB to offer fresh longer-term funding after TLTRO’s demise.

The central bank’s hands are tied by the vast amount of excess liquidity that’s already weakening the impact of monetary tightening. Even after more TLTRO repayments and the ECB’s shrinking bond portfolio are taken into account, excess liquidity could be roughly €3.5 trillion by the end of 2023, all else being equal. That’s only about 15% lower than current levels.

“There’s still too much liquidity chasing too limited issuance and you just don’t know where to park the cash,” says Geoff Yu, a senior strategist at BNY Mellon.

“To begin introducing measures to counteract balance sheet reduction at this juncture would be strange,” says Jussi Hiljanen, a strategist at SEB.

ECB President Christine Lagarde also seemed to play down that prospect after the central bank’s last policy meeting, saying that its standard facilities remained available. She was referring to operations that provide liquidity on a weekly and three-month basis: the MRO and the LTRO. Interest on those facilities is 50 basis points above the ECB’s deposit rate, and smaller lenders forced to use them after paying off TLTRO loans would suffer a drag on profits.

Because of that, not everyone has ruled out the ECB stepping in to support struggling banks, even if the provision of fresh liquidity does appear to run counter to the fight against inflation. “If the ECB wants to play it safe, it’ll offer new LTROs at more or less the deposit rate,” says Cluse at UBS. “It’s about risk management.”

--With assistance from Harumi Ichikura.

Author: Alexander Weber, Libby Cherry and Alice Gledhill