When Exondys 51 was approved to treat Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a deadly disease that puts kids in wheelchairs by the time they are teenagers, there was no proof the drug actually slowed the disease. That was seven years ago. The company still hasn’t provided conclusive data to this day.

The drug’s maker, Sarepta Therapeutics Inc., has so far reaped more than more than $2.5 billion in sales from Exondys 51 and two related drugs. All three were cleared via a US regulatory shortcut called accelerated approval that allows companies to market medications before completing definitive trials in cases where patients have few or no treatment options.

In the case of Exondys, Sarepta’s confirmatory study didn’t even begin until four years after it was approved and won’t be completed until 2024, eight years after it started selling the drug.

This is not uncommon. A Bloomberg News analysis of Food and Drug Administration databases found 19 drugs with accelerated approvals whose confirmatory trials are still listed as delayed as of April. That includes studies that are past their official due dates as well as trials running behind schedule. The analysis also found another seven accelerated approval drugs with studies behind schedule that weren’t categorized as delayed because the company had submitted some data to the agency.

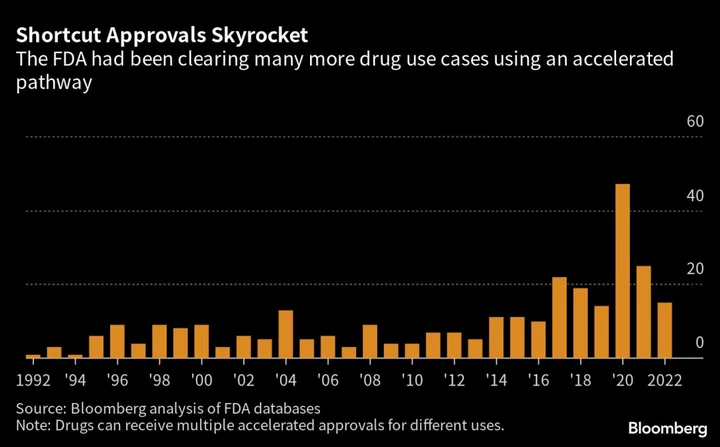

The accelerated approval pathway was created in 1992 in part to get promising HIV therapies before lengthy trials were completed. Patients’ desperation for treatments prompted the creation of the program and is a driving force to this day. The accelerated approval pathway allows the agency to quickly approve a new treatment if early results, typically from lab tests or scans, suggest it is “reasonably likely” to work.

Exondys was approved on data showing it slightly raised levels of a muscle protein dystrophin that’s missing in people with muscular dystrophy. The types of studies used for a standard FDA approval are designed to show that a person either gets better or stops getting worse as a result of a given drug. For a patient with muscular dystrophy, a successful trial could show a treatment keeps a patient out of a wheelchair for longer than someone on a placebo, for example.

What started out as a relatively obscure way for drugmakers to get new medicines to patients, accelerated approval is now a business model for some companies. Critics argue the FDA hasn’t done enough to force companies to produce conclusive data on drugs they’re already selling.

When it approved Exondys in 2016, the FDA knew it was making a controversial decision. Some experts felt the small increases in protein levels wouldn’t be enough to help patients but parents pushed hard for its approval. A top agency official at the time acknowledged the studies had serious flaws but said she didn’t want to hold those “against the patients.” Sarepta sought approval for Exondys in Europe, but regulators rejected it in 2018 saying the studies “were not satisfactory for showing that the medicine was effective.” The company appealed that decision, but the regulators held firm.

Since then, Sarepta has gotten two more drugs for muscular dystrophy approved in the US through the accelerated pathway.

“Sarepta is a poster child for an absolutely outrageous and inexcusable lack of any kind of oversight or enforcement,” said Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research, a nonprofit think tank. Sarepta said it is “fully committed” to completing the trial for Exondys and attributes the delays to a variety of factors including some requirements imposed by the FDA. A confirmatory trial for the company's other two drugs is enrolled and expected to be complete in 2025.

The success of Exondys, according to Sarepta, has allowed the company to raise billions of dollars that it has plowed back into gene therapy research and manufacturing that could help far more patients. The gene therapy program “wouldn’t have existed without the Exondys approval,” said Sarepta CEO Douglas Ingram. He argues time is of the essence when it comes to approving drugs for muscular dystrophy.

“These kids are dying,” Ingram said in an interview earlier this year. “If we get a six month delay, 200 kids will die, 200 more kids will be in a wheelchair, 200 more kids will go on a respirator, 200 more kids will not be able to use their arms or feed themselves.”

Sarepta’s now in front of the FDA again, seeking accelerated approval for a gene therapy for muscular dystrophy. A decision is expected by the end of this month. In a study in 41 patients, the therapy had mixed results: It failed to clearly improve patients’ overall ability to stand, walk, climb, jump and run when compared with a placebo. It did boost levels of a version of the protein dystrophin, another key goal of the study. The findings weren’t dissimilar to those of Sarepta’s other drugs.

New Law

Companies are required to conduct additional trials to prove the drug works after an accelerated approval, but until recently there hasn’t been pressure to do that quickly.

Seeking to change that, Congress passed a law in December that says the FDA “may” require confirmatory studies be underway at the time of an accelerated approval. It spells out a process the FDA can use to withdraw accelerated approvals, too. “Congress gave us the teeth,” FDA Commissioner Robert Califf said in January.

Not everyone is so sure. The new law is subject to interpretation and doesn’t eliminate the possibility of delayed trials, says Thomas Hwang, a physician at Harvard Medical School. Drugmakers can appeal a proposed withdrawal to the FDA commissioner, but details of how the process would work are unclear. And the FDA can’t immediately force accelerated approval drugs off the market after failed trials, said Bishal Gyawali, a cancer doctor at Queen’s University in Canada.

Meanwhile, people are taking drugs every day that haven’t met the FDA’s typical standard for approval. Yale University physician Reshma Ramachandran said that in 2020, a patient of hers developed colon inflammation after being treated for follicular lymphoma with a drug that had received an accelerated approval for that use. The patient needed surgery to remove part of her colon and the cancer wasn’t cured, Ramachandran said.

The next year, the drug’s maker announced it was withdrawing the accelerated approval for that type of cancer. Secura Bio Inc. says the withdrawal wasn’t based on safety signals, but rather it couldn’t afford the cost of the bigger trials that were required for full approval. The drug, Copiktra, remains on the market for other types of cancer.

Pulling Back

Amid growing controversy over the approval pathway, the agency is trying harder to get these drugs off the market when the required confirmatory trials aren’t completed or fail to prove drugs work. Last year, seven drugs lost accelerated approvals, tied with 2021 for the most ever, according to a Bloomberg News analysis. The withdrawals were done voluntarily by the companies, often at the agency’s request but not always.

Over the past three decades, around 300 applications have used the accelerated process, mostly for cancer medicines. In some years, more than 20% of all new drugs that hit the market came from this pathway.

Following the US, other countries have also devised expedited approval mechanisms. But in most countries other than Japan and Canada, the short-cut approvals come with expiration dates, according to a 2022 review by FDA officials. The EU has an expedited pathway, though it only allows a drug onto the market for a year at a time, encouraging companies to more quickly produce data showing a treatment works.

There have been some remarkable medical advances that have come through the accelerated approval pathway, like Novartis AG’s leukemia drug Gleevec. Accelerated approvals have expanded the use of blockbuster cancer immunotherapies such as Merck & Co.’s Keytruda and Bristol Myers Squibb Co.’s rival medicine Opdivo. But even for Merck and Bristol’s drugs, which are highly effective and well proven in numerous types of cancer, some accelerated approvals for certain cancer types were later withdrawn.In recent years, the use of the accelerated pathway has spread to more contentious arenas such as Alzheimer’s disease, where doctors disagree on whether scans or lab tests can reliably predict whether a drug works. Biogen Inc.’s Alzheimer’s drug Aduhelm may be the best example of this. The company’s two big trials produced contradictory results — one study showed it worked and one did not. An FDA advisory panel voted against approving it through traditional channels in November 2020.

In an unusual move just seven months later, the agency decided to use the accelerated pathway to approve the drug amid pressure from patient advocates. The FDA gave Biogen more than eight years to conduct a third big trial, which is underway.

After the Aduhelm controversy, the Department of Health and Human Service’s Office of Inspector General looked into how much the FDA’s program was costing taxpayers. According to the OIG report, the federal Medicare and Medicaid programs spent over $18 billion between 2018 and 2021 on accelerated approval drugs whose confirmatory trials ended up being delayed.

“People could be spending the last year of their lives taking something that ultimately turns out to be a dud,” Yale’s Ramachandran said of the accelerated approval pathway. “They could have been trying something else.”

On Friday, the FDA gathered a group of outside experts to debate the merits of Sarepta’s gene therapy to help guide the agency in its approval decision. After hours of back-and-forth over the murky data and numerous pleas from parents of kids with the disease to approve the drug, the scientific and medical experts on the panel were split. Two consumer and patient representatives tipped the final vote in favor of Sarepta’s therapy by a margin of 8 to 6.

It sets up the agency for another tough decision. If an approval comes, some analysts are predicting over $3 billion in annual sales.

--With assistance from Anders Melin.

Author: Robert Langreth, Fiona Rutherford, Immanual John Milton and Madeline Campbell