The Japanese government will test demand in the bond market with auctions in key 10-year and 30-year maturities this week after investors baulked at the yields on offer in sales last month.

The Ministry of Finance will sell ¥2.7 trillion ($18.4 billion) of 10-year notes on Tuesday and ¥900 billion of 30-year securities on Thursday. The debt offerings come as investors watch how much the Bank of Japan is willing to let benchmark yields rise after tweaking its yield curve control program in late July.

Traders are looking for signs that domestic yields are not yet high enough to prompt Japanese investors to load up at home and offload foreign holdings like Treasuries, European and Australian bonds. That potential repatriation risks exacerbating this year’s global bond selloff — the European Central Bank said in May a shift away from low interest rates in Japan could test the resilience of worldwide debt markets.

“Investors are probably seeking higher yields as US long-term yields have increased, especially after the BOJ gave more flexibility,” said Ayako Sera, market strategist at Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank Ltd. “Although super-long yields have risen somewhat, their levels are not high enough to encourage life insurers and pension funds to buy aggressively,” she said, adding that traders are more concerned about the outcome of Japan’s 30-year bond auction this week than the 10-year sale.

A dropoff in demand for Japanese government bonds reflects the challenges the BOJ will face in trying to unwind a super-easy policy that’s been in place for a decade. Rising interest rates will make it pricier to borrow money and if they trigger a strengthening in the yen, that may weigh on Japan’s exporter-heavy share market. Higher yields will also mean that the government’s debt-servicing costs will climb next year.

That costs will increase 11.5% from the previous year to ¥28.1 trillion next year at the budget request stage, according to a document seen by Bloomberg.

A worsening in Japan’s finances should drag on investor confidence toward longer bonds, but the way the system is structured means that Japan’s auctions won’t fail. The finance ministry requires 20 primary dealers — Japanese banks and brokerages and their foreign peers — to each bid for at least 5% of the planned issuance if needed, meaning the government will never fall short of demand when offering JGBs.

Bond auctions in Japan last month underscored the weakness of demand for debt as investors waited for higher yields.

At a 20-year note auction the so-called tail, or the difference between average and cut-off prices, was the widest since 1987, a sign of reduced investor appetite for the bonds. That sent 20-year yields higher in the following days, reaching a seven-month high of 1.42% on Aug. 23. A two-year debt sale last week, meanwhile, drew the lowest bid-to-cover ratio since 2010, in another indication of sluggish demand.

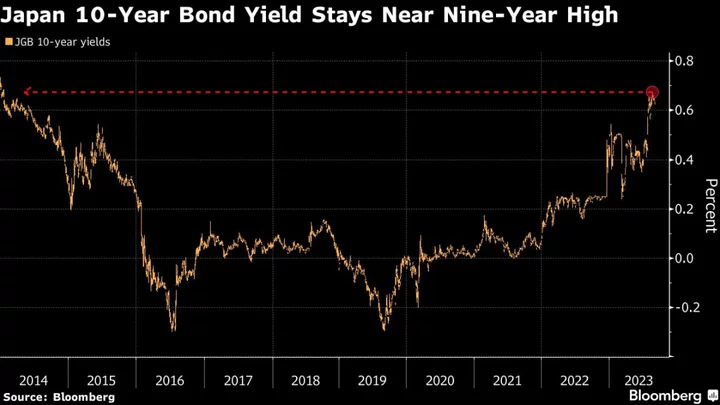

Japan’s 10-year yield traded at 0.64% on Monday after reaching a nine-year high of 0.675% on Aug. 23. Traders have been testing the BOJ’s resolve to prevent a too-rapid rise in yields after it tweaked YCC to effectively allow it to climb as high as to 1%. But the central bank has been stepping into the market to support bonds when yield increases were rapid.

The yield on the 30-year debt climbed to a more than seven-month high of 1.69% on Aug. 23 before stabilizing at 1.65% on Monday.

As long as 10-year yields remain around current levels, “it is likely that markets will only see short-covering demand,” said Shoki Omori, chief desk strategist at Mizuho Securities Co. “There is growing vigilance ahead of auctions and that’s likely to continue until market participants see auction results for September.”