The latest climbing season on Mount Everest, the world’s highest peak, is set to become one of the deadliest-ever, raising questions about whether Nepal is issuing too many permits to maximize tourist dollars.

The director of Nepal’s tourism department, Yubaraj Khatiwada, told Bloomberg News the death toll currently stood at eight, and that five other people are missing.

The number of fatalities looks set to surpass the 11 deaths logged in 2019, when images of massive traffic jams at the summit spread around the world. The deaths come after the Nepali government issued a record 478 permits.

The deadliest year in Everest’s climbing history was 2014, when at least 17 local staff were killed, mostly from a major avalanche, according to data tracked by the US-based non-profit organization The Himalayan Database.

Permits for foreigners to climb Everest cost $11,000 and have already raised more than $5 million for Nepal’s economy this year. The government has resisted making significant changes to cap the number of permits issued.

Many people are “seduced and enamored by climbing Mount Everest, and there’s nobody there that will tell them ‘no’ because they’ve paid the money,” said Alan Arnette, a mountaineering blogger who climbed Everest in 2011. Climbing operators and authorities have not taken significant safety measures to avoid harming profits, he said. “It’s a pure and simple business decision.”

Khatiwada said the government is taking the fatalities seriously. In a phone interview with Bloomberg News, he said Nepal requires climbers to be at least 16 years old. They must also submit a doctor’s certificate that says they’re medically fit.

“The death rate is quite high this season because of the climate and climate change,” he said. “There is no other reason. We are trying our best to reduce the risks, but mountaineering itself is risky.”

Landlocked Nepal, which is one of the most impoverished nations in Asia, has benefitted from a boom in mountaineering tourism — driven in part by the growing wealth of neighboring nations, including India and China.

While the world’s highest mountain — which stands at about 8,849 meters (29,032 feet) — is also accessible through China, climbers there are required to first scale an 8,000 meter peak, leading many to flock to Nepal, where there are no such rules. As many as 97 Chinese climbers attempted to summit Everest this year, making them the largest national cohort, followed by the US and India.

Many new local operators have opened in recent years to meet the surge in demand, but their guides sometimes don’t have sufficient expertise to spot even tiny risks that can quickly turn fatal at high altitudes, said Arnette.

“You’re going to have some people that are climbing that are inexperienced with unqualified guides,” he said. “Being at that altitude and under that physicality, the demands are just unpredictable. And as a result, you don’t know what you don’t know.”

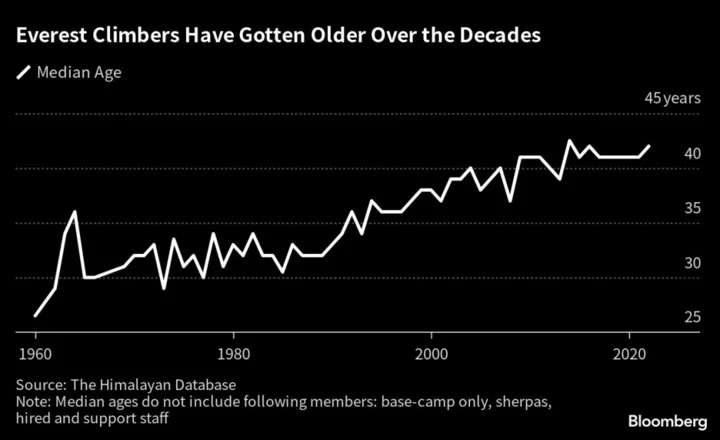

Climbers on Everest are also getting older, which has heightened the risks. The median age of mountaineers attempting Everest is now 42, compared to 34 in 1982.

Recurring safety concerns have done little so far to dent demand. A viral photo in 2019 showing climbers stuck for hours at the summit shocked the world, but for many, reaching the top of Everest is still the ultimate feat of human endurance.

(Rewrites second and third paragraphs with correct death toll, number of missing. Removes chart.)

Author: Low De Wei, Kevin Varley and Adrija Chatterjee