Denmark may have seen the worst of its housing-market slump and any economic impact should prove less painful than in neighboring Sweden, the country’s central bank governor suggested.

In an interview with Bloomberg Television on Monday, Christian Kettel Thomsen of Nationalbanken appeared sanguine about prospects for home values.

“I believe our housing market is quite stable,” he said. “We have experienced quite a fall in prices since last summer.”

Denmark’s property prices showed a second month of gains in April, according to real-estate data provider Boligsiden. Earlier in May, Nordea said that values had fallen about 6% so far, and predicted that the cost of an apartment may not reach a trough until the second half of 2024.

Along with many of its peers, Denmark saw a spurt in house-price growth during the pandemic. Such economies are more likely to face a cooling in home values, according to a global outlook from the International Monetary Fund last month.

While Sweden’s house-price declines may have exacerbated the hit suffered by an economy predicted by the European Commission to see the bloc’s biggest contraction this year, such an effect is less likely in Denmark, Kettel Thomsen said.

The state of the country’s housing market “should also be seen in the light that it followed some price increases in recent years,” he observed. “We see the households as quite financially robust.”

That can be seen in the loan impairment levels at the country’s commercial banks, he said. These remain “very, very small.”

Most Nordic housing markets have rebounded at the start of the year, helped by a decline in energy prices, even as analysts expect further declines amid continued monetary tightening.

Apartment prices in Sweden have gained for three months while the values of single-family homes have also stabilized following a 15% slump in the market from post-pandemic peaks. Housing prices in Norway have gained for four months, while in Finland, prices of old one-family houses fell 3.1% in the first quarter from the previous three months.

“In our forecasts, we still see some moderate declines over the year, and that’s still our view, even if things seem to be leveling out,” the governor said of the Danish market. ““But we don’t see it as a bomb under the Danish economy.”

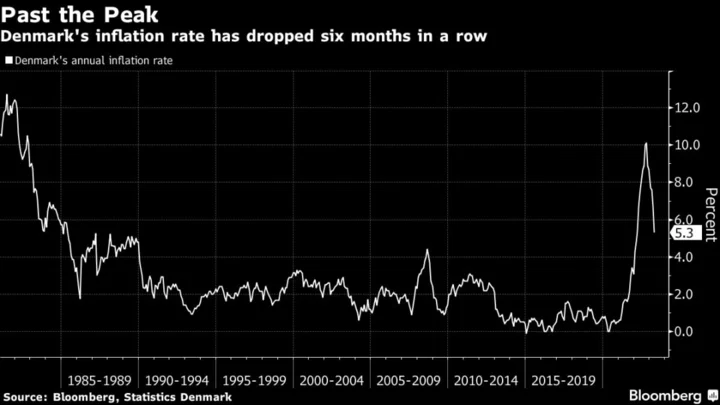

Like elsewhere in Europe, Danish consumer costs have shot up on higher prices for energy and food. Inflation peaked at a four-decade high of 10.1% in October but has since dropped to 5.3%. While the central bank doesn’t have an inflation target, it’s part of its mandate to secure “stable prices” through its currency peg.

Questioned on prospects for consumer prices, Kettel Thomsen said that his focus is similar to that in the neighboring euro zone. Denmark’s currency is pegged to the single European currency, meaning that it closely follows monetary policy the European Central Bank.

“We’re talking about what they will do in the ECB, which I don’t know, but I’m sure they’re looking for indicators on future price pressures and price expectations,” he said. “It’s not so much a question about the level of interest rates, but what’s the data on inflation going to be.”

Thomsen, 63, started as governor Feb. 1, joining from a job as vice president at the European Investment Bank, following a career that mainly has been shaped by high-ranking roles at the Danish prime minister’s office as well as at the finance ministry.

(Updates with further comments in eighth and 11th paragraphs)