Irina Panyushkina is a dendrochronologist — a scientist who studies tree-ring dating to understand past environmental conditions — at the University of Arizona. In early 2022 she was planning to do summer fieldwork in Siberia, for her research on the links between climate change, Russia’s freshwater systems and Arctic ice formation. Her work had already been delayed years by Covid-19.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine, and it slammed to a halt again.

Dmitry Nicolsky, a geophysicist at the University of Alaska at Fairbanks who researches thawing Arctic permafrost, managed to stay in touch with some of his Russia-based colleagues as the war started to unfold. But over time that contact stopped, and with it key information-sharing.

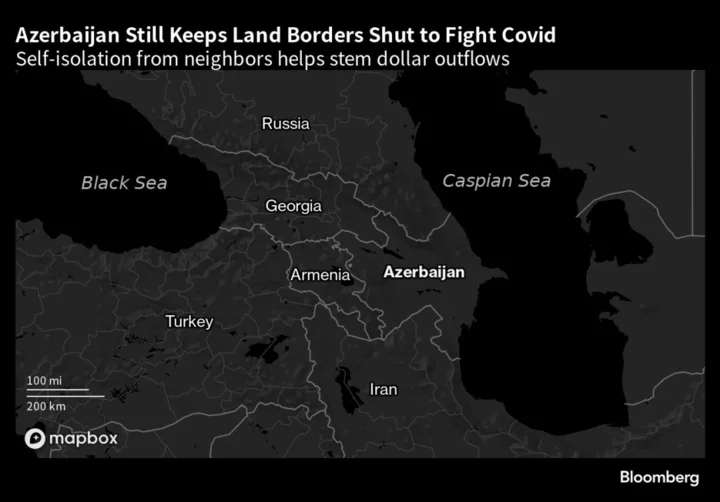

Florian Stammler, an anthropologist at the University of Lapland in Finland, was unable after the invasion to return to Russia’s Sakha republic in northeastern Siberia, where he’d long been measuring the impact of global warming on the nomadic, reindeer-herding Nenets people.

These projects represent a small fraction of the Arctic climate research that’s been derailed by the war in Ukraine. Studying the fast-warming top of the planet is crucial to efforts to mitigate global warming and understand its dynamics at lower latitudes. Arctic climate scientists tend to be a close-knit community, as normal professional rivalries are flattened by the borderless, existential threat of climate change.

But the war upended that status quo: Now geopolitics are a main determinant of whether scientific projects can move forward.

Read More: Why the Arctic Is Being Threatened by War and Climate Change

Most EU and NATO member countries have suspended or sharply limited funding for scholarly work involving Russia, a country that holds roughly half of the world’s Arctic territory. Sharing data is largely banned and the limited communication that’s still possible is nerve-wracking, as former scientific colleagues worry about jeopardizing each others’ careers or safety.

Finding ways to restart stalled science will be a recurring topic of conversation at a major Arctic conference in Iceland this week, where for the second year in a row, Russian scientists will not be present.

Asia will play an increasingly pivotal role in the Arctic, having heavily invested in polar science capabilities in recent years, said Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, former president of Iceland and the conference’s chairperson, in an interview on the eve of the gathering. “Japan, Korea and China have modernized their research vessels with ice capability more than any other country in the world in the last five to 10 years,” Grimsson said.

A fundamental question for delegates to consider is whether “meaningful Arctic science” and “meaningful global climate science” can be done at all without access to data from Russia’s Arctic, Grímsson said.

Nicolsky’s research on permafrost has been supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), one of the major American bodies that stopped funding new projects involving Russia under White House guidelines. The NSF also pulled out of most existing projects, unless they could be adjusted to focus on non-Russian parts of the region. (A European Commission decision had a similar impact on European funding.)

The project involved collecting temperature readings from more than 250 permafrost monitoring sites in Russia, Alaska and Canada, and mapping key changes. Arctic permafrost is estimated to hold 1,700 billion metric tons of frozen and thawing organic carbon, at least twice what’s already in the Earth’s atmosphere. As it thaws, that gas is released, accelerating warming, which in turn speeds up thawing in a dangerous cycle.

Most of the planet’s permafrost lies within Russia and Nicolsky was relying on Russian colleagues to collect that data. “We cannot remove this piece from the equation,” he says. “It’s like removing a couple of wheels from a car and trying to drive it home.”

He’s spent hours poring over legal documents, trying to find a clear path to continue working together. While the NSF did not withdraw funding, Nicolsky’s collaborators in Russia are unsure whether it’s safe to accept it, or even to communicate with US-based scientists.

Studying melting permafrost without Russian data is “like removing a couple of wheels from a car and trying to drive it home”

Last year he was still able to receive some data out of Russia, “but this year it was just gridlock,” he says. “I spent countless meetings trying to facilitate collaboration with our Russian colleagues, to find different means, and it was falling apart from both ends, on the Russian side and on the US side.”

A fractured Arctic Council

It’s not just communication breakdowns. Nicolsky adds that the logistics system underpinning Arctic research — helping scientists ship equipment across borders and facilitating visas — is fundamentally “broken.”

Much of that kind of support had been provided by the Arctic Council, a pan-governmental group of Arctic nations formed in 1996 that includes Russia. A week after the invasion of Ukraine, it suspended all activities.

Read More: Russia’s Next Standoff With the West Lies in the Resource-Rich Arctic

The Council had been a critically important body for bringing states and Indigenous groups together on Arctic issues, leading to legally binding agreements on matters such as scientific cooperation, search and rescue operations and marine pollution. Prior to the war in Ukraine, a Council working group was studying a possible pan-Arctic agreement to fight and prevent wildfires, of the kind that tore through Siberia and Canada in recent years.

That and other work has gradually resumed, though not at the normal speed or level, says Morten Hoglund, the Norwegian chair of the Council. Since his country assumed the rotating position from Russia in May, Hoglund has worked to find a way to unstick the body, which operates by consensus. A decision in August to allow member countries to communicate in writing, without having to meet, is an important step toward easing logjams and eventually allowing a few key projects to move forward. Still, the Council is not yet in a position to approve new projects, and even if they were, “there are layers of challenges, not only political but also practical,” that discourage collaboration with Russia, he says. “We have to be realistic.”

Progress will likely depend more on the willingness of the Council’s Western nations to engage with Russia than the other way around, says Jennifer Spence, a public policy expert with Harvard University’s Arctic Initiative. “It wasn’t Russia blocking anything, it was the seven other like-minded states,” she says of the Council’s paralysis. “In many ways, Russia has been ready to come to the table from day one and been pretty open about the fact that they wanted the Arctic Council to continue to function.”

The new rule allowing written communication will be reviewed at the end of the year, and the next few months will reveal whether member countries use it to agree to work on new Council projects. “If Russia puts on board a project, who might be willing to partner with them? And if they don’t, will Russia reciprocate?” Spence asks.

As political sensitivities continue to trump science, researchers are becoming increasingly fearful of running afoul of governments and institutions, in case they endanger themselves or their foreign colleagues. Like many of the scientists interviewed for this article, Nikolay Shiklomanov, a geography professor at George Washington University in Washington, DC, is originally from Russia. Since coming to the US 30 years ago, he's made a point of trying to support young scientists back home whenever he can. Since the invasion, he says he has been deluged with letters from Russian colleagues trying to leave, but it’s now almost impossible for them to get a US visa.

He believes many Russian researchers will try to keep collecting data but for now they are afraid to share it outside the country, either by email or on US portals. “We have no idea what will happen to the future of the science, and our science specifically, in Russia.’’

Chinese scientists step in

Even if data is still collected, it may no longer be calibrated to work with Western models, says Panyushkina, whose project had to be scaled back in order to keep its NSF funding with limited access to Russian colleagues and no ability to collect new tree-ring samples in Russia. She suspects some of Russia’s previous collaborations with Western researchers will be filled by Chinese scientists who can still easily travel to Russia for work, squeezing out North American and European experts: “I have a feeling that the Chinese researchers will basically replace us.”

Stammler, the anthropologist in Lapland, once hoped Finland’s shared border with Russia might position it to act as an intermediary between Western and Russian scientists, but Finland’s accession to NATO scuppered that, he says.

Read More: Europe’s Green Revolution Threatens Indigenous Culture

For the past three decades, Stammler has spent months at a time living in remote communities on the Kamchatka peninsula in Russia’s Sakha republic, documenting how the Indigenous Nenets people are adapting to accelerating climate change. Over the years he’s formed close personal ties with some of the nomadic reindeer herders but now has no way to meet them. They can’t get visas to come to Finland and he can’t travel there.

Earlier this year, he tried to invite some Russian colleagues to participate remotely in a roundtable he was attending in Canada, but the agency funding the conference told him that would mean no Canadian officials could attend, and he was forced to uninvite them. The best workaround he’s found so far has been to meet Russian colleagues in non-EU countries, like Turkey or Inner Mongolia. China might be another option, he says.

“From my side, I can say that cooperation with Chinese colleagues has increased, not decreased” since the war in Ukraine, he says.

Chinese scientists and government officials are at this week’s Arctic Circle Assembly in Iceland. A record 2,000 attendees from more than 70 countries will discuss more granular issues as well, ranging from increased Arctic shipping, to critical minerals, to Indigenous stewardship of natural resources, to the many Arctic repercussions of climate change.

Also at the conference is Edward Alexander, an Indigenous leader of the Gwich’in people in Alaska. The week Russia attacked Ukraine, he recalls, he was waiting for a Russian check to support pan-Arctic wildfire prevention research. The work was being done under the umbrella of the Arctic Council, where he serves as a delegation head, and the US and Russia were co-leads on the project. Needless to say, the funds never arrived.

Alexander’s team was able to pick away at the project but progress was slowed. Now, he and Hoglund will launch a new Norwegian wildfire initiative on Thursday evening. Designed to get communities and countries to share best practices about preventing Arctic fires, it’s the kind of creative workaround that may be necessary as countries settle into a new geopolitical order, and until more sweeping work can be done by the Council.

“Trust was shattered by the war in Ukraine,” Alexander says. “It’s going to take a long process of rebuilding trust between states to get to the place where we were before.”