China is attempting to diffuse risks from its $9 trillion pile of off balance-sheet local government debt, without resorting to major bailouts.

That path forward is a treacherous one for President Xi Jinping’s government. To thread the needle, the provinces and cities whose borrowing drove the world’s largest infrastructure boom will need to roll back their spending and restructure debt — all without drastically dragging down economic growth. If they fail, it could thrust the world’s second-biggest economy into a prolonged malaise.

At the center of this dilemma are local government financing vehicles, companies set up across China to borrow on behalf of provinces and cities but not explicitly in their name. Xi’s government has sought to turn these firms into profitable businesses so they’d no longer need government money to pay the interest on their debts.

But interviews with employees at six such firms in separate provinces suggest the effort isn’t working in poorer inland regions.

Several companies haven’t been able to generate enough income to pay interest on loans. Banks are unwilling to lend, investors are shunning their bonds, bonuses are being cut and it’s becoming harder to find viable investment projects, the employees said, asking not to be identified due to the sensitivity of discussing government finances publicly.

If the central government avoids a bailout, the burden of repayment will fall increasingly on local governments or on banks tasked with lowering interest rates and extending maturities on the debt. Both options will limit the capacity of local governments and banks to support economic growth.

It’s a worry for investors, as well, since any default on LGFVs $2 trillion of bonds — which account for nearly half the country’s onshore corporate debt market — would destabilize China’s $60 trillion financial system, producing global shockwaves.

“The most important variable impacting China’s economic growth over the next two years will be the success or failure of local government debt restructuring,” said Logan Wright, director of China markets research at Rhodium Group. “A collapse in local government investment would be comparable to the economic impact of the crisis in the property market.”

China’s Ministry of Finance and the National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s economic planning agency, didn’t respond to questions on the matter.

The Communist Party’s Politburo hinted in July at steps to resolve the debt risks, and Beijing now appears to be following through. It’s allowing Chinese provinces to raise about 1 trillion yuan ($137 billion) from bond sales, which can be used to pay-off LGFV debt, according to people familiar with the matter.

While that’s a fraction of all LGFV debt — the International Monetary Fund estimates a total of 66 trillion yuan this year — the move has increased market confidence in the companies’ bonds. Beijing is also considering using the central bank to provide liquidity to the most-strained LGFVs, local media Caixin reported.

But these fixes were not Beijing’s first choice. It set in motion a plan before the pandemic to inject state-owned assets into the companies and permit them to enter new business areas to generate enough cash to service debt on their own. This was known as the “market-oriented transformation” model.

An example from a mountainous district in southwest Chongqing shows how that plan is falling short. A local government-owned company there borrowed billions of yuan to build roads, water pipes, factory buildings, and affordable housing. It transformed a former mining area into a development zone for factories, which converts coal into chemicals.

Economic output in the zone increased fourfold in just over a decade. Like other LGFVs, the infrastructure built was provided for free or very cheaply to the public and businesses as part of their responsibility to promote “public welfare” and economic growth.

To make the LGFV more financially self-sufficient, the local government in Chongqing gave the company a license to sell coal to factories. But profit from that business wasn’t enough to cover the company’s interest payments. As a result, the most recent reports show the company’s short-term debt is six times its cash on hand.

“We are indeed talking about transformation,” said an employee who works at the company in Chongqing. “But to be honest, so far we have not found out any good path to transformation yet.”

China has thousands of these LGFVs spread out across the country, businesses that were set up to develop local economies. Last year alone, they pumped more than 5 trillion yuan into the economy, according to a tally from Rhodium Group.

The companies rely on local governments for income, in the form of payments for infrastructure and pure subsidies. They also borrow from banks and by selling bonds, which are generally seen as carrying an implicit government guarantee of repayment.

That was fine so long as banks were willing to roll over the company’s debt when it was due, and so long as the economy was growing fast enough that the local government made enough revenue to pay subsidies to the company.

But that funding model is now under unprecedented strain. Firstly, a record amount of LGFV debt is maturing. Secondly, local governments, especially in poorer areas, are seeing revenues drop due to a two-year slump in home sales.

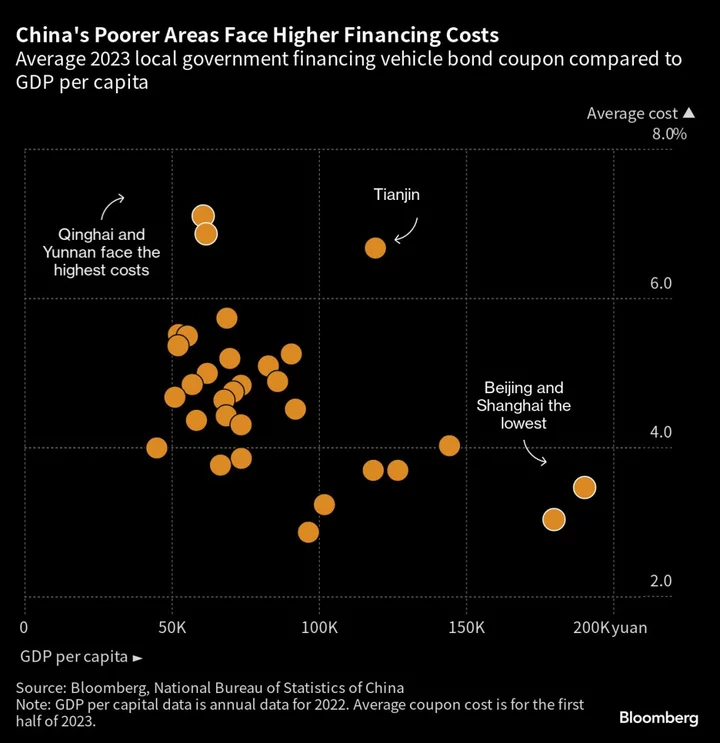

And thirdly, banks and investors have become less convinced Beijing will bail out some LGFVs if they go bust, pushing up the interest rates on bonds and loans, and making it harder for weaker companies to access financing.

Beijing’s plan was to make LGFVs more self-sufficient by injecting state-owned assets — ranging from hotels to mines and tourist sights and even utilities like electricity, water and gas — and giving them permission to move into new business areas.

That’s worked in some wealthy areas like Shanghai, but China’s poorer areas – the vast inland provinces where about half of the population lives – often lack the resources needed to make it work.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimates that by 2022, the median LGFV had cash on hand worth less than half short-term debt.

Market forces are only adding to the problems. Since Beijing began hinting pre-pandemic that it wouldn’t help local governments with bailouts, bond buyers are demanding LGFVs in poorer areas issue debt at higher interest rates or shorter maturities – increasing debt service costs and refinancing pressures.

Some regions have been frozen out of the bond market entirely.

“We’re in a total mess right now — no one would like to buy our bonds,” said an accountant surnamed Yang, who works at a LGFV in western China. Salary levels at the company have been frozen since 2016, and staff are leaving, she added.

An employee at a separate LGFV said banks are demanding interest rates of nearly 10% for refinancing.

Cutting staff salaries hurts local economies, but a drop in LGFVs other expenses would have national consequences. Various estimates from economists suggest the companies fund anything from a fifth to more than half of China’s total infrastructure spending.

LGFVs are already missing payments at record rates on bills owed to construction companies and shadow banks, leaving projects unfinished and investors without returns.

Moutai Tensions

Even in places where local governments have valuable assets, politics can stand in the way of using them.

For example, Guizhou province is home to some of the country’s most financially strained LGFVs, yet owns the country’s second-largest company by market value: liquor producer Kweichow Moutai Co., worth about 2.23 trillion yuan. The company was pressured into buying a stake in a local road-building LGFV when it ran into financial trouble in 2020. Moutai shareholders, which include investment funds and retail investors, were not happy, and have resisted further cash injections.

As a result of these struggles, some asset additions by local governments were purely cosmetic.

“We have bus companies, heat, water, sanitation companies as our subsidiaries nominally, but we don’t have actual control of them,” said Yang. “We have been talking about transformation for like 10 years, but it is not happening,” she added.

Toll Roads

One good asset available to local governments are highways, which can charge tolls. LGFVs involved in that business have a chance of achieving debt-sufficiency.

For example, a toll road operator in southwest China generates enough cash from tolls to service its current debt. Salary payment hadn’t been a problem, said a staffer in the company’s investment and financing department.

But the problem is that now the company has built a lot of roads, additional ones aren’t generating good returns. So to fund new investments, the company is pursuing a partial transformation into a private equity and venture capital fund.

Thanks to their government ownership, LGFVs can borrow more cheaply than most private companies or start-ups can. For example, LGFVs in Hefei, the capital of eastern Anhui province, have become famous in China for making returns worth many multiples of their equity investments into electric vehicle and LCD-screen manufacturers.

But, like the other options, it isn’t a model that can work easily for economically disadvantaged regions.

“It’s difficult to find good projects to invest in because the real economy isn’t doing well,” the road company staffer said.

To ensure infrastructure investment in poorer regions won’t collapse, Beijing has been allowing local governments to sell so-called “special purpose” bonds — 3.8 trillion yuan of them this year to build roads, railways and bridges. The issuance of those bonds, though, isn’t growing fast enough to make up for a fall in LGFV borrowing.

Local government officials don’t want to have their careers ruined by having their LGFVs default on bonds, so they continue to rustle up cash, sometimes at the last minute, to help them service their debt. That leaves them with less money to spend on infrastructure spending.

As a result, economists are expecting infrastructure investment in water, roads and other low-return projects to slow over the next decade, lowering Chinese growth.

According to one former LGFV executive, the future is clear: “The historical mission of LGFVs to invest in pure public welfare infrastructure projects has come to an end.”

--With assistance from Shuqin Ding and Alice Huang.