China can avoid a “balance sheet recession” if authorities take decisive actions to boost government borrowing and spending to stimulate the weakening economic recovery, a state think tank researcher said.

Contrary to economists who say high debt limits Beijing’s ability to add significant stimulus, the government still has ample space to leverage up in part because it owns massive state assets, Liu Lei, a researcher at the National Institution for Finance and Development, said in an interview. The think tank writes reports on areas such as China’s debt, financial risks, and the banking sector, and recommends policies to various government agencies.

Li argued Beijing should prioritize lifting growth, which he said would naturally “dilute” debt levels in the economy.

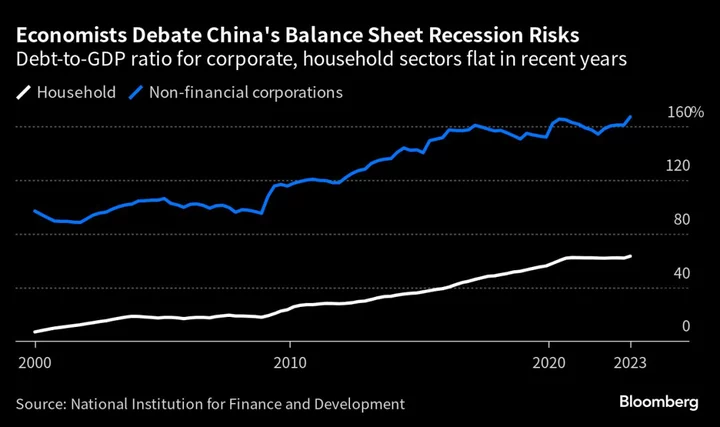

The comments from Liu add to the debate over whether China is in a “balance sheet recession” — a term coined by Richard Koo, chief economist at the Nomura Research Institute, to explain Japan’s descent into stagnation in the 1990s.

Liu discussed his views in a recent interview, which has been lightly edited for clarity:

Are there risks that China is in a “balance sheet recession”?

China is not in a technical “balance sheet recession” because property and asset prices haven’t plunged and have kept about the same level in recent years.

But we are seeing signs of it. Households and the corporate sector have already exhibited typical behaviors of repairing their balance sheets — but we can reverse these signs if appropriate policies are taken.

Our policy recommendation is for the central government to issue more sovereign bonds, which requires removing the 3% target for the fiscal deficit-to-GDP ratio.

We think that’s the only possible way for China to escape expectations for recession this time. We’ve paid a lot of attention to Koo’s research and we largely agree with his advice.

Does the government still see stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio as an important policy objective? Will that limit the scope of stimulus?

The overall debt ratio is set to climb this year. The ratio is determined by both debt levels and the size of the economy, and currently the latter is having a bigger impact. Nominal growth has been slowing — partly due to lower inflation — while debt is likely to expand by about 10% this year, resulting in a higher ratio.

Stabilizing the debt ratio is a mid- to long-term objective in order to prevent financial instability. I think the goal now is not to stabilize or reduce the debt ratio in the short term, which is impossible. The most important objective must be to recover economic growth to above its potential level in the short term. Debt levels will definitely rise during this process.

When a country becomes a dominant player in the global economic system, its policy space will be drastically larger. We need to take rapid policy action to lift growth and ensure the economy expands at a relatively fast speed for another 15 to 20 years.

Even counting the 40-to-60 trillion yuan in local ‘hidden debt,’ the debt ratio for China’s government is still lower than that of the US and Japan. In addition, the Chinese government has a lot of assets in the form of equity in state-owned enterprises, and natural resources, like land. The government’s balance sheet is very healthy.

What are your specific recommendations?

From a scholar’s perspective, it’s best if the deficit target is raised to higher than 5% in one go. Such a level of actual fiscal spending was in fact achieved through local governments’ hidden borrowing in the past. But policy makers may fear lifting the deficit too fast will cause panic or lift inflation expectations.

Fiscal spending can go to infrastructure and ensuring stalled housing projects are completed, as well as industries that advance China’s competitiveness, such as semiconductors and artificial intelligence.

Will the financial system be able to absorb additional sovereign bond issuance? What can the central bank do?

Monetary policy has been very loose, but its effectiveness has been declining in the past two years and is now close to zero. We’re now facing a liquidity trap, where companies won’t borrow no matter how much you cut interest rates.

The PBOC should buy more sovereign bonds and reduce the share of medium-term lending facility in its balance sheet. This will send a longer-term signal to the market and avoid market volatilities from investors’ misinterpretation of its monthly MLF operations.