The child-care industry is set to lose a $24 billion lifeline this weekend. The expiration of the pandemic-era funding could leave 3.2 million children without spots in care as providers are forced to limit operating hours, cut resources or even close centers.

Bloomberg News reporter Kelsey Butler hosted a LinkedIn audio event discussing what the change could mean for the labor market. Allison Robinson, chief executive officer of recruitment marketplace the Mom Project, Shelley Zalis, CEO of the Female Quotient, which advocates for gender diversity in the workplace, and Bloomberg News reporters Reade Pickert and Ryan Teague Beckwith, who cover economy and politics respectively, participated in the discussion. It’s condensed here for length and clarity.

Kelsey Butler: Let’s explain this cliff — what happens on Sept. 30?

Reade Pickert: Back in March of 2021, when the Biden administration passed the American Rescue Plan, there was $24 billion in funding for child-care providers. Child-care providers used this federal funding for a variety of things. Many supplemented employee pay, they hired more staff, they made improvements to the daycares and generally used it as a way to offset rising costs.

On Oct. 1, thousands of providers aren’t going to close their doors. But what happens is, without the funds, providers can’t pay their staff as much, people leave for better paid jobs and fewer teachers mean you can’t have as many students. At a certain point it doesn't make sense to operate anymore. On the flip side, if providers want to maintain all of that staff and maintain that number of children, they need to raise tuition to keep up with these costs. And that in turn will end up pricing out some families from care.

Kelsey Butler: Companies are thinking about this differently than they were five or 10 years ago. Allison, what are you hearing from your seat?

Allison Robinson: Over the last 30 days, this has gotten more attention by employers. Seeing the kind of real world implications this is going to have on their workforce is very much top of mind, particularly as they look to retain this critical diverse segment of their workforce. Employers are really thinking about educating themselves on the implications — and it can vary greatly depending on the state you’re in. So it really starts with troubleshooting: What are the challenges? Then getting really practical around the role that they can play — whether that be helping to subsidize the cost, or looking at childcare providers … and the support they can offer as quickly as possible.

Shelley Zalis: Child care isn’t a short-term challenge. This is a long-term conversation. We are losing our best leaders to caregiving and we need to retain them. It’s corporations’ responsibility to really think about how we’re going to keep our caregivers. And it’s not just women. It’s men and women — it’s parents. And caring is not just with children, it’s also elderly care. We have to think about this as a really big issue. This is a problem for the economy, for families, for corporations.

One solution that we can put into place is to give all employees a care wallet and let them use that money as they wish, whether it’s for elderly care or child care or self-care.

Butler: Why hasn’t fixing this problem had traction in Washington?

Ryan Teague Beckwith: This actually has been addressed before and it was at a time when America really needed women in the workforce. And that was during World War II. In 1943, Congress passed a bill that created a national system of child care in order to allow women to continue working since so many men were away fighting the war. But after the war, when all the men returned, they just shut [the nurseries] down. In the ’70s, there was another push for this that got all the way to Richard Nixon’s desk. He vetoed it.

Butler: Are there any data points that really drive this issue home?

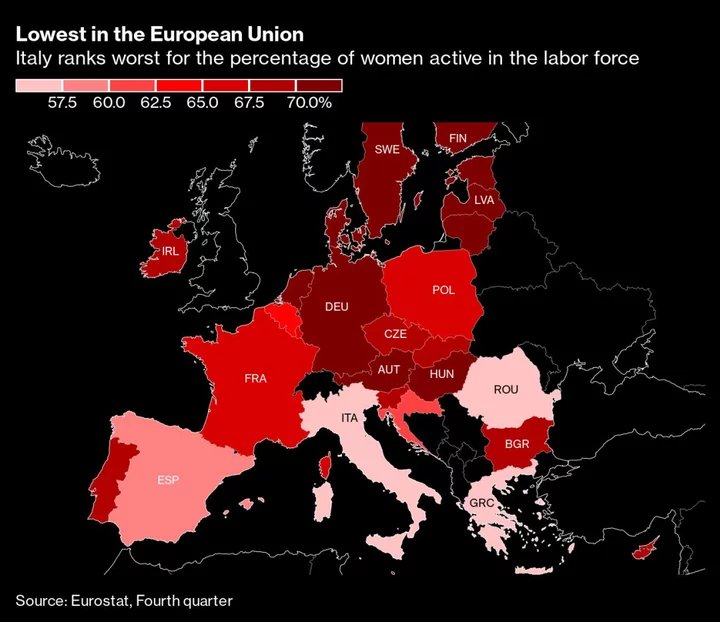

Pickert: When we talk about labor force participation, or said another way, the share of people who are either working or looking for work, we often talk about age groups. For women aged 25 to 54 — the group that’s most likely to have young and elementary age children — participation climbed to a record high in June. And it’s held near there for the last couple of months.

When we think about the reasons behind this, it’s reopening childcare providers, rising wages, and this availability of remote and more flexible working arrangements. Widespread inflation and the rapid increase in prices over the last few years has pushed others to join the workforce who may not have joined otherwise. The number I’ll be watching is whether we see that progress reverse if we start to see childcare providers close.

Robinson: My thought goes to the over 3 million children and their moms and dads that can be impacted by this pending deadline. I’m so proud of how far we've gone in the last 18 months in really driving moms’ workforce participation. How do we get care for those 3 million children so a mom can make the choice that’s right for her?

--With assistance from Reade Pickert, Ryan Teague Beckwith and Ella Ceron.