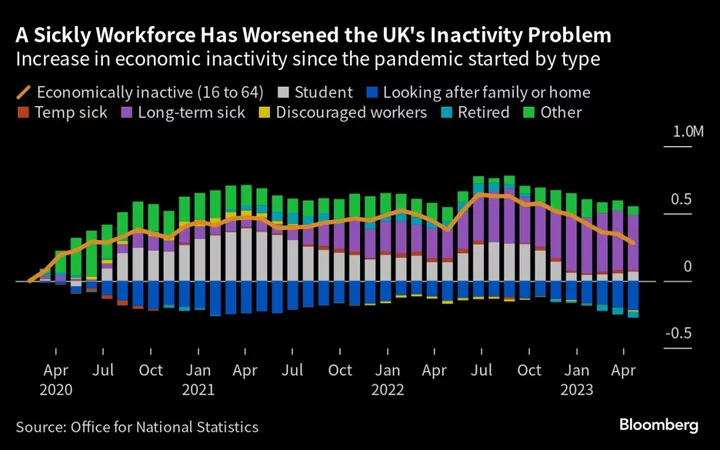

The number of workers kept out of Britain’s jobs market by long-term sickness dropped for the first time this year, adding to signs that the nation is moving away from a crisis of inactivity.

Long-term sickness was down 30,000 in the three months to May compared to the peak seen in April’s data, the Office for National Statistics said Tuesday. That’s despite National Health Service waiting lists remaining at a record high. It was down 2,000 on the previous quarter and marked the first decline since the three months to December.

The figures are an indication that inflationary pressures from the labor market may ease in the months ahead. While wages still are growing faster than the Bank of England says is compatible with its target, unemployment ticked higher as a result of more people joining the workforce, suggesting upward pressures on wages may have past its peak.

“Further falls in economic inactivity as the jobs market returns to its pre-pandemic state is unambiguously good news, with men in particular returning to work,” said Charlie McCurdy, economist at the Resolution Foundation.

A shortage of workers is one of the factors that’s kept UK inflation above levels elsewhere in the Group of Seven nations, underpinning expectations the Bank of England will have to raise interest rates again.

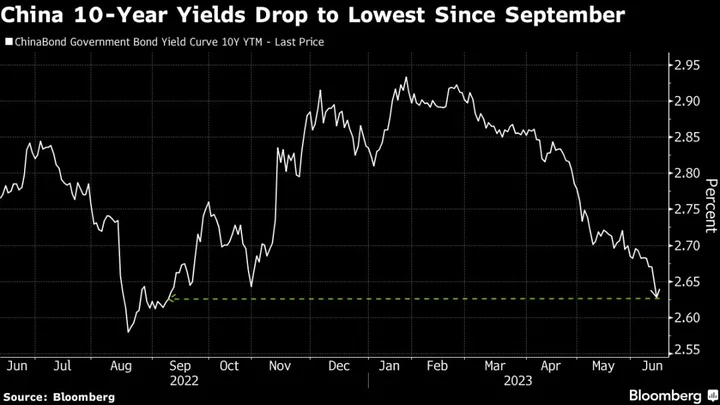

While traders maintained bets for another half-point hike in August, they trimmed wagers on where Bank Rate will peak, with pricing now split between 6.25% and 6.5% by early next year. The repricing Tuesday comes as data showed the UK unemployment rate unexpectedly rose because of the flow of more people back into work.

The yield on 10-year UK government bonds fell 4 basis points to 4.60%, outperforming US Treasuries and European bonds. The pound jumped as much as 0.4% after the release to $1.2913, the highest since April 2022, before paring its advance.

Sterling is the best performing currency across the Group of 10 this year, bolstered by interest rates that tower over peers.

Total economic inactivity — those not in work or seeking a job — has now fallen by 360,000 from the post-pandemic peak, suggesting that the labor market is finally loosening. This helped to drive unemployment up 0.2 percentage points to 4% in the three months to May.

A large number of workforce drop-outs since the pandemic have tightened the labor market, helping to boost wages and causing more persistent high inflation.

Long-term sickness has been the biggest contributor with massive waiting lists for NHS treatment, long Covid and deteriorating mental health among the factors blamed. It’s still up 412,000 on pre-pandemic levels despite the easing in the most recent data.

More than half of the increase in inactivity since Covid struck has now reversed, providing more workers to compete for a shrinking number of available job vacancies.

The inactivity rate fell to 20.8% in the three months to May, down 0.4 percentage points on the previous quarter. It’s now 280,000 above pre-Covid levels.

While the rise in long-term sickness came to a halt, other factors were more important for the latest drop in inactivity.

The main declines came from those who had retired, those who were looking after family and for other reasons, such as those who have not yet started looking for a job. It could suggest that those sitting on the sidelines of the labor market are feeling the pressure from the cost-of-living crisis and now need to seek more work.

“The deteriorating health of the nation’s workforce should come as little surprise given the strain placed on the NHS with waiting lists now comfortably exceeding 9 million throughout the UK,” said Brett Hill, head of health and protection at consultancy Broadstone.

--With assistance from Lucy White, Constantine Courcoulas and Greg Ritchie.