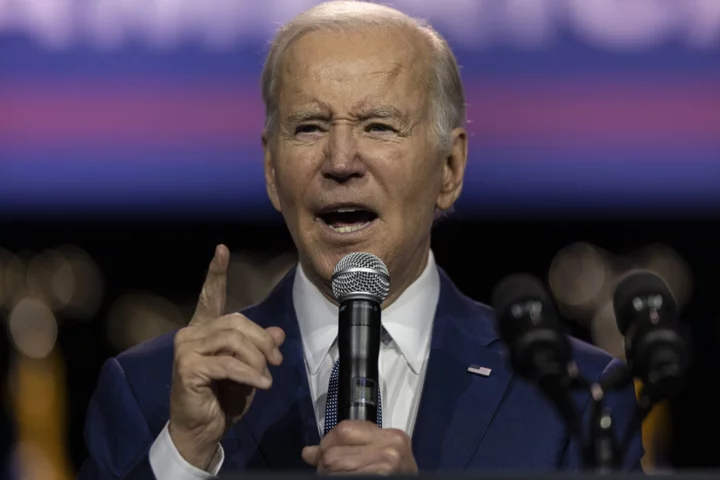

The Biden administration is trying to make it hard for China to say no to engagement by seeking a flurry of meetings and phone calls, a strategy aimed at easing tensions and painting President Xi Jinping as recalcitrant if he refuses.

The approach, described by people familiar with the matter who asked not to be identified, has involved proposals of meetings and calls from the lowest level all the way up to a possible conversation between Xi and President Joe Biden, something that has been stalled for months now. It’s also meant to appease allied nations in Asia and Europe that are anxious the US isn’t doing enough to ease tension that some fear could lead to open conflict.

The people acknowledge the strategy could paint the US as a supplicant seeking the favor of a powerful adversary. It has already garnered skepticism from critics of the Biden administration who warn it makes the US look weak.

A White House spokeswoman didn’t immediately reply to a request for comment.

“This is a smart but risky play,” said Evan Medeiros, former senior director for Asia on the Obama National Security Council. “It looks credible to Europe and Asia. But it also risks reinforcing China’s view that we need them more and they can drive the US-China agenda.”

The push started in earnest in recent weeks as a furor died down over an alleged Chinese spy balloon that traversed the US in February and was then shot down by US fighter jets. A visit by Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen to the US, which included an unprecedented meeting on US soil with House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, further complicated any effort to ease tensions.

In the time since, the administration has floated the idea of calls and meetings with senior leadership in China, including between Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin and his counterpart and Trade Representative Katherine Tai and China’s commerce minister.

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo, and climate envoy John Kerry are all planning trips to China. That planning has also been accompanied by a broader messaging campaign from Yellen and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan saying the US doesn’t want to sever economic ties — just address the possible national security concerns.

Biden’s team is also looking to establish what it calls guardrails around a relationship facing deeper, more systemic strains around economic competition and China’s continued partnership with another US adversary, Russia. Beijing has rejected US attempts to frame the relationship around “competition” and “guardrails,” with Foreign Minister Qin Gang saying in March the intention is to “contain and suppress China in all respects.”

So far, China has responded tepidly to the US requests. It has ignored Austin’s outreach for calls and hasn’t publicly responded to his request for a meeting on the sidelines of the Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore set for June. China hasn’t even said if Commerce Minister Wang Wentao will travel to Detroit for an Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting, where Tai has floated the idea of bilateral talks.

It’s also unclear when Biden will speak with Xi, something the US president first mentioned in February amid the balloon furor. On Wednesday, Biden said the call with Xi was still in the works, without providing a timeframe.

“China’s leaders probably assess that their strategy of freezing the relationship since the spy balloon shootdown has worked,” said Dennis Wilder, the Central Intelligence Agency’s former deputy assistant director for East Asia and the Pacific. “They may feel they have achieved a tactical upper hand in US-China bilateral diplomacy.”

See: China’s New Foreign Minister Meets US Envoy for First Time

The Chinese Embassy in Washington declined to comment. But Beijing has repeatedly stressed that the US must change its policies for ties to improve.

Even so, there are tentative indications that the strains that have marked the relationship in recent months may be easing. Qin met US Ambassador Nicholas Burns in Beijing on Monday for the first time since taking the position as China’s foreign minister, a symbolic move that may indicate Beijing’s willingness to allow more senior-level discussions.

“Due to the extreme anti-China hostility by the US government, China is giving the US the cold shoulder, refusing to let a number of senior US officials to come to China,” said Gao Zhikai, a former Chinese diplomat who served as translator to the late leader Deng Xiaoping. “China’s position is clear — stop violating the One China policy and stop promoting Taiwan separatism and sedition.”

Critics of the Biden administration’s approach have been similarly blunt in their skepticism.

“I just don’t understand this sort of desperation to have a meeting and the ardent suitor behavior that the Biden administration is exhibiting,” Representative Mike Gallagher, who chairs the newly created China Select Committee, said at an event in Washington on Wednesday.

“There does seem to be this kind of renewed push on engagement right now from the administration, or just sort of this idea that we can engage in some areas, we can compete in other areas,” Gallagher said. “All of it, I think, creates a lot of confusion in terms of our overall strategy.”

Biden Administration Tamps Down Talk of US-China Decoupling

Gallagher and other critics have also made the administration’s strategy more complicated with a steady drumbeat of criticism of China as well as a series of trips to Taiwan.

Members of Gallagher’s committee are planning a trip to Taiwan in early summer, according to a person familiar with the matter. Final attendance on the trip isn’t set, but the whole committee has been invited, the person said.

Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan Speaker You Si-kun is also set to visit Washington next week and will meet members of the House Select Committee on China, according to two other people familiar with his plans. You, a member of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party, hosted a US congressional delegation in Taipei last month. He said he believes McCarthy will still come to Taiwan after he postponed an earlier trip and met Tsai in California.

US officials such as Assistant Secretary of State Daniel Kritenbrink and Sarah Beran, the National Security Council’s senior director for China and Taiwan, have maintained working-level ties with the chief of mission at the Chinese embassy, according to people familiar with the matter.

“More intensive diplomacy is necessary to reduce the growing risk of a crisis that neither side seeks at a time of acute domestic challenges,” said Jessica Chen Weiss, a Cornell University professor and a senior fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute. “Diplomacy is not a gift to the other side but an indispensable tool for tackling problems.”

--With assistance from Iain Marlow.