Some Senate Democrats are pushing the Biden administration to impose tough limits on hydrogen tax credits they say will ensure the fuel lives up to its climate-fighting potential. Hydrogen advocates warn that could end up stifling the nascent industry instead.

The campaign is aimed at the US Treasury Department, which is writing rules for claiming the tax credit worth as much as $3 for every kilogram of hydrogen produced over a decade. The Biden administration is counting on the fuel to decarbonize power plants, clean up heavy industry and meet climate targets. And the incentive created in last year’s landmark climate law is essential to driving tens of billions of dollars in spending on hydrogen production and manufacturing electrolyzers to extract the gas from water.

Without “rigorous guardrails,” the resulting investment could spur a net increase in US greenhouse gas emissions, Senator Jeff Merkley warns the Internal Revenue Service in a drafted letter seen by Bloomberg News that a handful of other Democrats are expected to sign. “The IRS must ensure that the billions of dollars at stake are used to promote truly low- and zero-carbon hydrogen production and infrastructure.”

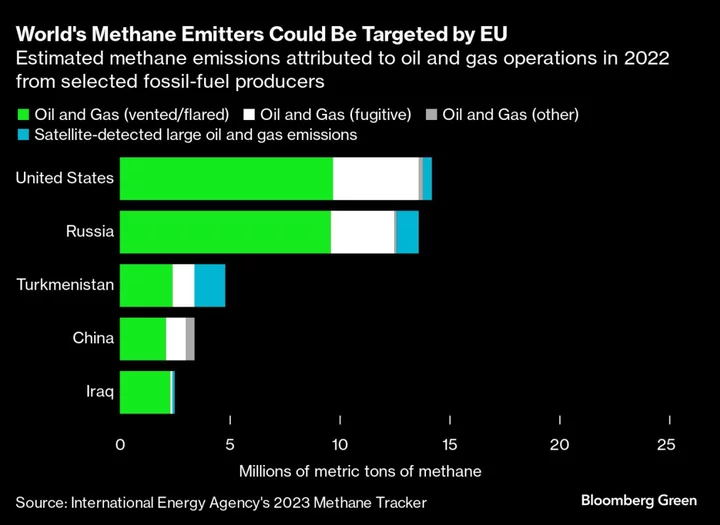

The lawmakers — along with a coalition of environmental groups — want the full credit available only for hydrogen ventures offset by new, clean electricity supplies located in the same region and operating during the same hours. Otherwise, they argue, surging energy-intensive hydrogen production might spur more generation of fossil fuel-based electricity to fill the gap — boosting carbon dioxide emissions equivalent to 26 new coal plants each year.

Proponents have outlined options for some existing power resources to qualify as new, clean supplies — such as nuclear plants operating at night or recently built renewable facilities.

Hydrogen advocates say the restrictions would decimate the industry’s potential value — and stop some planned projects in their tracks.

“You are putting brakes on the intent of the IRA in a way that will definitely stifle the growth of the industry and the decarbonization benefits,” said Frank Wolak, president of the Fuel Cell and Hydrogen Energy Association, whose members include Amazon.com Inc., Southern Co., Toyota Motor Corp. and Plug Power Inc.

The potential limits are a particular threat to nuclear- and hydro-powered projects. While some companies are eyeing new nuclear-powered hydrogen production operations, none envision building a nuclear plant. With a requirement for new generation, capacity increases or off-peak power, nuclear advocates say many ventures wouldn’t pan out.

“I can’t see a world where we have anywhere near the level of hydrogen production from nuclear that we would,” said Benton Arnett, director of markets and policy at the Nuclear Energy Institute. A strict mandate for new, clean electricity would “pretty much take most nuclear off the table.”

Congress reserved the highest tax credit value for the most cleanly produced hydrogen and gave the Treasury Department discretion in how to estimate emissions. Hydrogen supporters argue similar limits aren’t imposed on tax credits for electric vehicles and other technologies that also could boost demand for coal and gas power.

The department is on track to outline its approach by mid-August.

Analysts say a rapid hydrogen scale-up is critical to cutting emissions in coming decades as US power grids grow cleaner. “When assessing trade-offs of policy implementation, it’s important to understand the balance of considerable long-term emissions reduction benefits versus short-term impacts,” according to Rhodium Group research. While increased electricity generation to fuel electrolyzers could boost greenhouse gas emissions an estimated 34 million to 58 million metric tons in 2030, Rhodium stressed, the Energy Department estimates potential reductions from clean hydrogen could amount to nearly 20 times that in 2050.

Rachel Fakhry, a policy director at the Natural Resources Defense Council, says the government’s decision will dictate hydrogen’s potential as a climate savior — or villain. The goal has to be “preventing emissions increases and increased fossil fuel generation on the grid,” she said. Otherwise, it’s “completely contrary to the trajectory we should be on.”

(Updates with Rhodium Group analysis in 12th paragraph.)

Author: Jennifer A. Dlouhy