A bevy of US consumers who saw their credit scores boosted by government stimulus and a pause on student-loan payments during the pandemic are now seeing those scores slide back into subprime territory, according to the country’s largest store-card issuer.

As a result, Synchrony Financial has begun closing inactive accounts and curtailing card limits for a small portion of accounts, Chief Financial Officer Brian Wenzel said in an interview. The Stamford, Connecticut-based firm hasn’t felt the need to tighten underwriting standards for new accounts, he added.

“What we are seeing is people who are doing significant score migration — a 680 or a 690 going to a 620,” Wenzel said. “Folks who had paid down debt, their scores had gone up, and now they’re reverting back to more normal performance.”

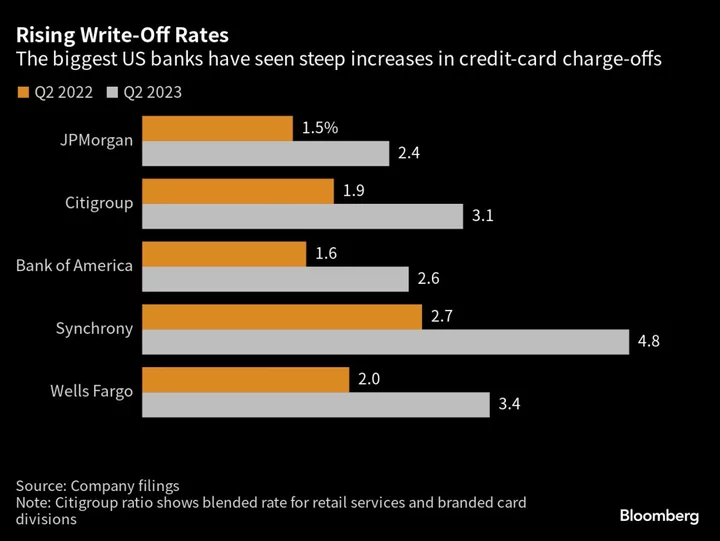

Wenzel’s company, which counts Amazon.com Inc. and Lowe’s Cos. among its largest partners, saw net income slump 29% in the second quarter to $569 million after it had to set aside more money to cover souring loans. The firm joined rivals in reporting a steep uptick in credit-card charge-offs, though industry executives continue to note that losses remain below pre-pandemic levels.

Still, per-share earnings of $1.32 topped the $1.23 average of analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg, and the firm said it now expects delinquencies — a harbinger of future losses — to return to pre-pandemic levels by the end of the year. The company had earlier forecast those levels would be reached by midyear.

“Credit continues to normalize slower” than at other firms, Wenzel said. “That was a concern for us as we walked into this.”

Shares jumped 1.9% to $36.17 at 2:07 p.m. in New York, reaching its highest intraday level since March. The shares have gained 10% this year, outpacing the 1.9% advance for the 72-company S&P 500 Financials Index.

The firm’s moves in recent months echo a study by the credit reporting firm TransUnion, which found that borrowers who’s credit scores jumped into a higher tier are “likely to fall back into some of the credit behaviors that they had displayed previously.” That research found that many new credit lines were being tapped by people who’d recently seen their credit scores rise sharply.

“We think other issuers may have overextended them,” Wenzel said. “If we saw someone go from a 790 to a 740 or a 720, we’re not going to do anything,” he said, adding that “it’s that migration into deeper subprime or nonprime that you want to be worried about.”