The neat two-story rows of white containers stretch right up to the towering cranes of the vast construction site. Clothes can be seen hanging in some of the windows.

The compound will eventually be home to as many as 5,200 workers, most of them coming from Asia. The Indians, Pakistanis, Filipinos and Turkmen are being employed by Orlen SA, Poland’s largest company and the government’s economic champion, to build a new $6.3 billion plastics facility at its sprawling refining complex.

About 600 kilometers (370 miles) south in Hungary, Chinese builders are milling around on a break, checking their mobile phones. They are helping construct one of three plants near the city of Debrecen, part of Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s vision for electric vehicle battery manufacturing to underpin the future Hungarian economy.

The notion of foreign workers filling gaps in the labor market is hardly unusual, and a chronic shortage is forcing employers across Europe to look further afield. But in these parts of Eastern Europe, that’s unmasked an awkward truth: Economic reality has caught up with some of the most vitriolic anti-immigrant rhetoric on the continent.

Politicians in Warsaw and Budapest have long railed against European Union plans for migrant quotas. Faced with hundreds of thousands of unfilled positions in a labor market that threatens to put a brake on growth, officials now argue thousands of arrivals from Asia are “guest workers” rather than migrants who will stay.

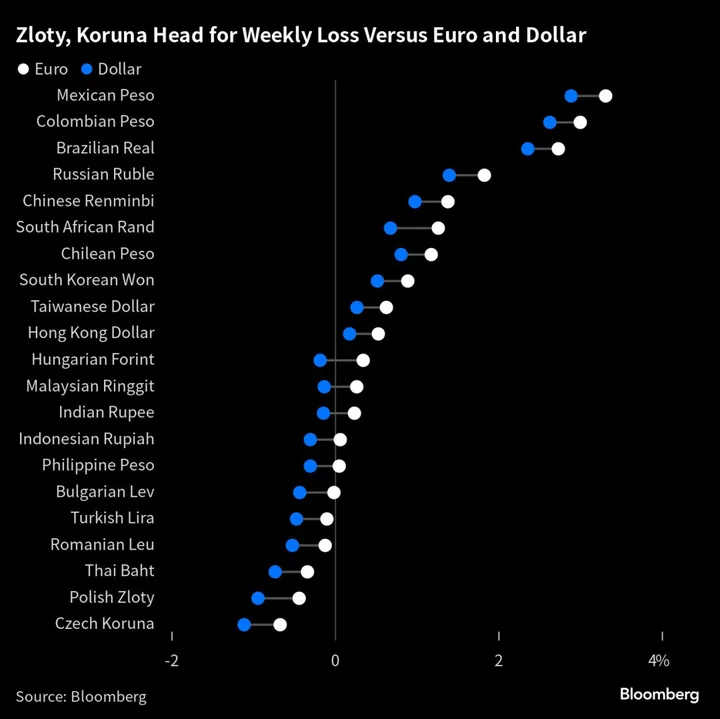

The change in the narrative is making them a target for political foes. Poland’s governing Law & Justice party, which is seeking a third straight term in what’s set to be a tight election on Oct. 15, last month abandoned a plan to fast-track visas after criticism from the main opposition party. In Hungary, Orban is being blamed for replacing locals with cheaper Asian workers.

“Of course there’s a shift,” Laszlo Papp, the mayor of Debrecen, said in an interview at his office last week. “But there’s a huge difference between the migration that we opposed and the issue of foreign workers, and the difference is control,” said Papp, a member of Orban’s ruling Fidesz party. “That makes it acceptable.”

Ever since the refugee crisis of 2015 and Germany’s decision to open its border, the populist leaderships in Poland and Hungary have cast themselves as the protectors of Europe’s Christian heritage.

Orban’s government notoriously built a fence to keep out refugees, illegally refused to process asylum seekers and put up billboards warning foreigners against taking away jobs in Hungary. Polish ruling party leader Jaroslaw Kaczynski said Muslims were a threat to Europe. Most recently, in July, the two countries sought to block an EU plan for member states to share the accommodation of arrivals from outside Europe.

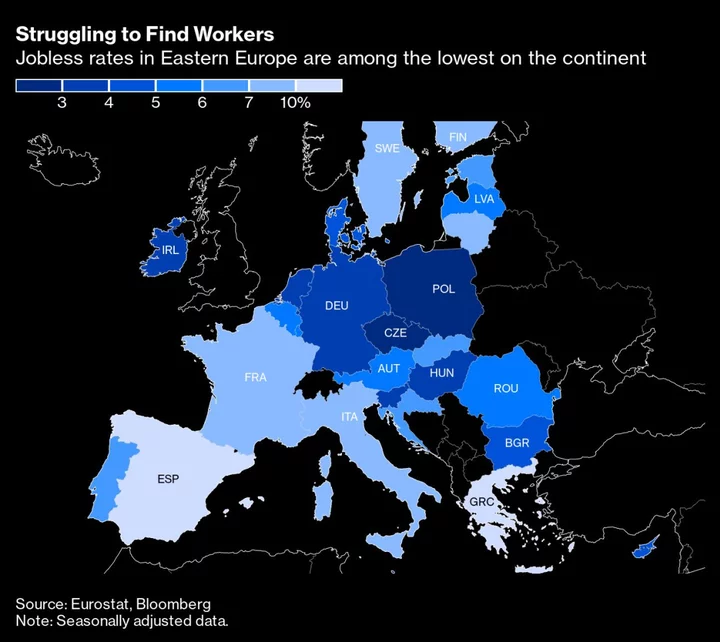

It’s a nativism that’s served them well at the ballot box in some of the least multicultural parts of Europe. But most eastern economies in the EU have jobless rates of 5% or lower, and at least 670,000 jobs remain unfilled across the region.

That’s prompting governments to act in the face of aging population and find millions of people to keep their economies running in the years to come. The shortage became more acute after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine upended the flow of workers across the border that many neighboring countries relied on.

In Hungary, Orban told corporate executives earlier this year that the struggling economy will need 500,000 new workers within two years if the country is to come good on investments in new battery plants worth about $15 billion. That’s equivalent to more than 10% of its current workforce. Parliament passed a law making it easier to bring in foreign workers while capping their stay at three years.

Poland needs to bring in at least 200,000 immigrants a year over the next decade to keep the current ratio of working-age population to retirees, the country’s social insurance institution estimated. That figure compares with 188,000 foreigners newly registered with it in 2022 as Ukrainians relocated because of the war.

The Czech Republic, where populist billionaire Andrej Babis was unseated as prime minister two years ago, has since approved higher quotas for visas for workers coming from the Philippines and Mongolia as it seeks to plug in the gap caused by missing Ukrainians.

“The calls from companies are really desperate,” said Labor Minister Marian Jurecka. The country will need about 300,000 more foreign workers by 2030 on top of the about 900,000 there are now, he said. “Lack of workforce is the main barrier for their growth.”

After being fed a diet of fear, uneasy electorates are being told the workers are key to investment projects to ensure growth outpaces Western Europe in coming years.

In Hungary, China’s Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd., or CATL, has started construction on an $8 billion battery factory, Europe’s biggest, near Debrecen close to the Romanian border.

Across from the site, some properties are becoming make-shift lodges for foreign workers. Earlier this month, as many as 50 Chinese laborers were found to be living in cramped conditions in a single-family home, prompting local authorities to launch a probe.

Polish oil and petrochemicals giant Orlen, which has close ties with the ruling Law & Justice party, is hosting thousands of workers to build its new plant. Seven rows of containers sprung up near Biala, a village of about 800 people on the outskirts of Plock in central Poland, where Orlen is headquartered.

The company started a campaign to reassure locals the influx was temporary, while the police deployed more officers to assuage concern about any rise in crime. It also ran an awareness campaign called “StopHejt” to counter racism. Leaflets and posters went up around the town and police officers held anti-discrimination workshops in schools.

“Employing large Asian workforce for megaprojects is a new necessity,” said Jakub Zgorzelski, a director responsible for the project. “These projects will need to be built with a large contribution from the Asian workforce.”

That stands in contrast with government rhetoric on the EU’s plan for member states to take a quota of arrivals from outside Europe and relieve the burden on states such as Greece and Italy. Orban told national radio on June 30 the EU’s proposal would force Hungary to “create migrant ghettos.”

Polish attitudes toward immigration will be tested again in October. Kaczynski, Law & Justice’s chairman and Poland’s most powerful politician, announced a plan to hold a referendum on the EU’s migrant relocation plan in conjunction with the election.

While the party is still portraying itself as the defender of Polish identity and security, one of its political weapons is now also a potential source of vulnerability.

The opposition, led by Donald Tusk, a former prime minister and European Council president, called out the government last month for letting in 130,000 workers from countries including Iran, Nigeria and Pakistan in 2022. Tusk said it was an attempt by the ruling party to stir divisions before the election. The government backtracked on plans to issue as many as 400,000 work permits a year to people from 21 countries including in Asia and the Middle East.

“Migration is not the most important issue in Poland’s October parliamentary election, but it could become salient if linked to national security concerns,” Aleks Szczerbiak, professor of politics at the University of Sussex in the UK, wrote in a blog published on Aug. 11. “In a closely-fought contest, it may play a decisive role in determining the outcome.”

In Biala, Orlen is making efforts to cater to the new workers as well as trying to win the hearts and minds of locals. The “container town” may even have a cricket field and two basketball courts and nearby churches are preparing to hold services in English.

Anto Darwin, a safety coordinator from India who lives in one of the containers, said people sometimes look at him in a strange way and he was once shouted at by a local. But the 32-year-old native of Chennai hopes to stay, regardless. “Once my daughter is one year old, I want to bring the whole family from Chennai and rent an apartment,” he said.

That’s when the economic need for workers and the politics of immigration could collide again. At the moment, the containers are home to about 500 people. As that figure increases, so might tension with the local Polish population, said Slawomir Wawrzynski, mayor of the Stara Biala municipality.

“We emphasize that these migrants are here just to work,” Wawrzynski said. “There are no problems with the migrants, so the anxiety is suspended. But if the number of migrants increases to a few thousand, which is expected next year, then problems could arise.”

--With assistance from Maciej Martewicz, Peter Laca, Barbara Sladkowska and Marton Kasnyik.

Author: Krzysztof Kropidlowski, Andrea Dudik and Zoltan Simon